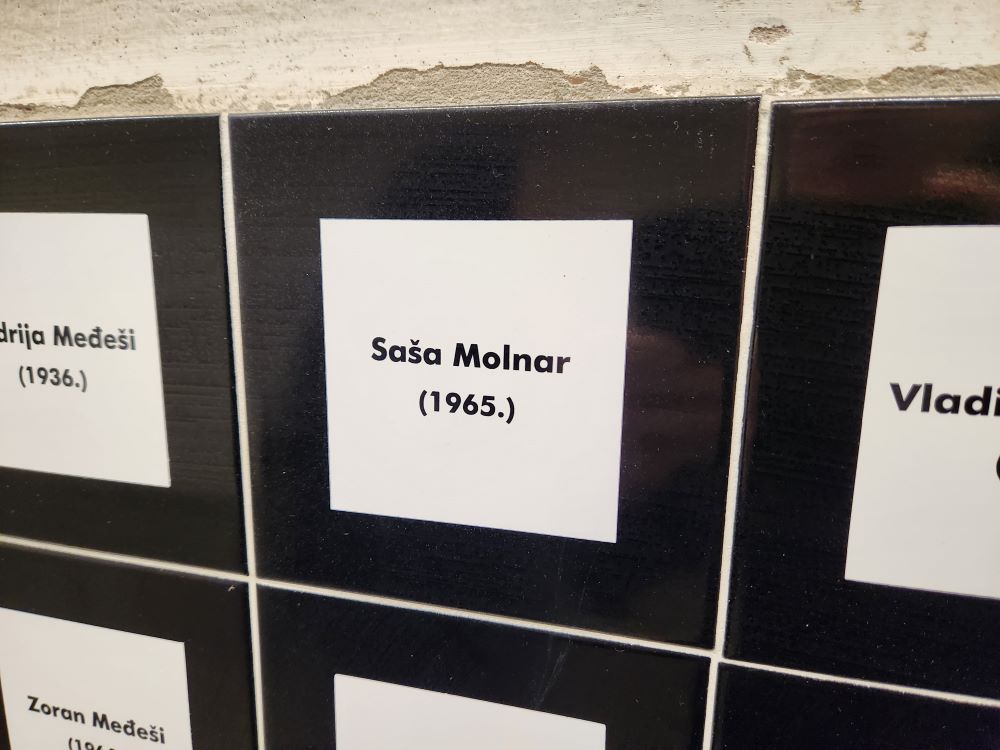

At a memorial site at the hospital in Vukovar, Croatia, Srs. Doroteja Krešić, right, and Teuta Augustini, say a prayer for Saša Molnar, the brother of Sr. Franciska Molnar and a victim of a 1991 massacre. The women are Sisters of Mercy of the Holy Cross. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

Editor's note: Our 2023 series, Hope Amid Turmoil: Sisters in Conflict Zones, began with reporting from Global Sisters Report international correspondent Chris Herlinger from Ukraine on the experiences of sisters in a country currently at war. The series now ends with Herlinger also reporting from Europe — this time from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, two countries that experienced wars three decades ago. Herlinger's reporting allowed sisters in those locales to reflect on the dynamics of peace and forgiveness in countries that were once conflict zones.

Before the "Homeland War" of the 1990s, the residents of Vukovar, Croatia, thought it a peaceful city. But a devastating tragedy interceded — and three decades later, the city lives in an uneasy peace, shrouded in memories of horrific tragedy and loss.

One of those who knows of such loss is Sr. Franciska Molnar, 68, a member of the Sisters of Mercy of the Holy Cross, who ministers at the congregation's home convent in Đakovo, a city about 35 miles west of Vukovar.

Molnar grew up in Vukovar, a port city on the Danube which overlooks the border with neighboring Serbia. She recalls it as a place where people got along. Residents did not think much of the mixing of Orthodox Serbs and Catholic Croatians — though the Croatian majority was conscious that, during the communist era, Catholics were often not favored for jobs.

Peaceful dynamics changed swiftly, however, when Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia in 1991 and the Yugoslav National Army, which included Serbian extremists, opposed the move, invading the country. Eventually Croatia won its war of independence but not before some 20,000 perished.

A fulcrum of the struggle was the fall of Vukovar in November 1991 after a nearly-three month siege. The city became the first European municipality to be totally destroyed since World War II, and was the site of numerous human rights violations against civilians. Witnesses at the time said that dozens of bodies lined Vukovar's ash- and debris-covered streets.

But perhaps notoriously, Yugoslav national forces forcibly took some 400 people from Vukovar's hospital — an institution founded by Molnar's congregation in 1940, though later confiscated after World War II by communist authorities.

Eventually about half of those were released — including a group of Catholic sisters — but others were transported to a farm outside the city and were executed. Some remain missing to this day; the bodies of others were found nearly a decade later in mass graves.

Among those who perished was Molnar's brother, Saša. He was 26 at the time and serving with Croatian forces. He was the father of two young children.

"He was defending his country," Molnar said quietly in an interview at the congregation's convent in Đakovo.

Molnar, who was not in Vukovar during the siege, said her parents stubbornly held onto hope that their son would return — sometimes even laying out clothes for him. When Saša's body was discovered in a mass grave nine years later, the family was devastated.

Molnar's own journey has not been easy, but she has been able to forgive her brother's killers. "I am open to all people, and even to those who killed my brother," she said.

The National Memorial Cemetery in Vukovar, Croatia, commemorates the victims of the Croatian War of Independence, called the Homeland War by Croatians. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

But Molnar underlines that belief with what she says is a truth about forgiveness: She says the act of forgiveness does not emanate from her, but from God.

"I feel it is God's grace that I can forgive," she said. "I feel that it is important to live by the Gospel, God's word. That's God's gift, God's work."

"The experience of forgiving helps me in my life, in the work I do," she said, which includes helping supervise a sister-run food bank in Đakovo. But she adds, "It's not always easy."

'Wounds that are still fresh'

Molnar's comments echo those of more than a dozen sisters interviewed earlier this month in Croatia and neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina about both the fallout from the wars of 30 years ago and about their current ministries that are helping, in often small ways, both directly and indirectly, to heal the wounds of lands once riven by conflict.

'The experience of forgiving helps me in my life, in the work I do. … It's not always easy.'

—Sr. Franciska Molnar

The sisters were not hesitant in discussing the 1990s wars — both those who experienced them as adults directly and those who were children at the time.

The women religious stressed that meaningful lessons can be drawn from the wars, particularly the need to forgive a nation's enemies and to remain close to people in need during conflict. But at the same time, the sister's focus now is on ministries that may have little direct connection to the past.

"The war is behind us; a new generation is coming," said Sr. Rastislava Ralbovsky, who is also a member of Molnar's congregation. "Our apostolate is focused on the needs of people now."

Yet, she said, "There are still effects felt by those who suffered."

That is true. To an outsider it is hard to miss that, even from a distance of three decades, the shadows of war are still discernible.

Evidence of bombardment at a hospital in Vukovar, Croatia, remains as part of a museum to commemorate events there. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

A surprising number of buildings damaged or destroyed by war still mark the landscape in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina — whether an abandoned train station in Vukovar, or, in Bosnia, burned-out houses in graceful snow-swept plateaus or still recovering hamlets.

While traveling by car with sisters in Croatia near the Bosnian border, one religious casually noted that, during the war, "this was a Serb-controlled area, out of Croatian control." Others mentioned that some sisters lost convents and even their lives in the war.

Of course, visiting Vukovar — whether in the memorial established in the basement of the still intact and operational hospital, or at the national gravesite for the victims of the Vukovar massacre — is something altogether different.

The weight of events there circle around everything, exposing vulnerabilities. Vukovar was rebuilt, but by several accounts has never fully regained its pre-war prosperity or footing: Its population dropped from about 46,000 in 1991 to 23,000 in 2021.

At a memorial site at the hospital in Vukovar, Croatia, a plaque commemorates Saša Molnar, the brother of Sr. Franciska Molnar, one of the victims of a 1991 massacre. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

On a recent visit to Vukovar, Srs. Doroteja Krešić and Teuta Augustini, fellow members of Molnar's congregation, found a plaque with Saša Molnar's name at the hospital memorial and said a brief prayer; that moment of avowed respect was a salve in a place of painful historical memory.

"What happened here was pure evil," Augustini said.

Earlier, Krešić recalled family traumas from the war — whether it was an uncle who was assaulted by Yugoslav soldiers or the family home being damaged by a military assault. "People always said the war won't last long," she recalled, acknowledging that that is something that is always said when wars begin, whether the World Wars, the wars in Croatia and Bosnia or the current war in Ukraine.

Posters at an exhibit in Vukovar, Croatia, commemorate the siege of the city in 1991. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

On the issue of forgiveness, Krešić said she finds solace and strength in the Gospel of Luke's reference to Jesus saying, "Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing."

But, like Molnar, she says that belief is not simply or glibly said and embraced easily. Krešić knows of a woman who was raped during the war, prompting to ask herself, "Could I forgive if I were from Vukovar?"

It is a poignant question — she said she feels "very close to those people and what they experienced." She said it is understandable that for many people, particularly those of her parents' age, it is not easy to forgive the aggressors.

"For many people, the war isn't finished," Krešić said. "There are wounds that are still fresh."

Sr. Rastislava Ralbovsky, right, and Sr. Marija Klara Klarić, members of the Sisters of Mercy of the Holy Cross, minister in a program that began in 1996 to help people coping with trauma and spiritual scars after the war. The program is based at the congregational convent in Đakovo, Croatia. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

Two sisters who know that well are Sr. Rastislava Ralbovsky and Sr. Marija Klara Klarić. Both are members of the Sisters of Mercy of the Holy Cross who minister in a program that began in 1996 to help people coping with trauma and spiritual scars after the war — be they veterans, war widows, or those who lost children.

The program was an outgrowth of the congregation's work in housing refugees from neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. It has since expanded to assist people with physical and mental disabilities, and it attracts Catholics of all ages needing spiritual sustenance.

Though Đakovo was not occupied, the sisters' convent was filled with refugees, and personal contact was important, with the sisters providing accommodation, food and spiritual care, whether that meant prayer or daily praying the rosary.

"It was a very dear, precious experience," Ralbovsky said, "to share someone's suffering, to show that we were here, to do what we could do at that moment."

'We have to forgive because we're Christians. We should leave it to God to render justice and judgment.'

—Sr. Damira Biškup

The sisters welcomed all, regardless of faith or nationality. And the sisters remain welcoming now — attentive to needs that include struggles with post-traumatic stress syndrome, a common concern with wives of veterans.

The wives are open to discussing their problems with the sisters — the men usually are not. "It's hard to reach those men (with PTSD)," Ralbovsky said. "It's like they are closed. They are still suffering, and their wives are still suffering."

The effects are still present and can manifest themselves in chemical addictions, depression and spousal abuse. "We try to assist the families we best we can," Ralbovsky said, adding, "It's a small drop in the sea of what we can do, of what should be done."

The abandoned railroad station in Vukovar, Croatia, destroyed during a 1991 siege, is evidence of destruction during the Croatian War of Independence. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

It is obvious, she said, that many families are still struggling and "very much in need of recovery." Sometimes it can feel like the needs are too overwhelming. And yet, Ralbovsky also knows there are men and families who have recovered — who come out of the experience renewed and hopeful.

Klarić said it is difficult to take in all the complexity and convergent issues related to war recovery. While some who are able "to put the war aside" even those who may be willing to talk about it some may face specific challenges — the experience of a combatant may not be the same as that of people imprisoned or tortured in a prison camp.

War anniversaries — even ones that are celebratory — can prompt moments of pain. "The effects of war are still there," said Klarić, who lived in occupied Bosnia for six months and who left the country in the midst of war with her mother, sisters and brothers, arriving in Croatia in 1992. "Time makes it a little bit easier, but it can never heal fully. The scar always remains visible."

Sr. Franka Bagarić is the provincial superior of the school sisters of St. Francis of Christ the King in Mostar, Bosnia, a city that was largely destroyed in the Bosnian war. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

'They had to process that pain'

She and Ralbovsky take solace in knowing that whatever work they do helps people in any stage of recovery, "People are free in front of us — they trust us, believe in our vocations," Klarić said. "They feel God's closeness through us."

In their ongoing program to assist people with spiritual needs and challenges, the sisters are guided by the biblical dictum about Jesus serving those who hunger, thirst and are "the least of thee."

"We have ill people, hungry people, lonely people in our programs, who are seeking love and understanding,” Ralbovsky said. “With our programs, we are trying to achieve the kingdom of God in small ways. That's a huge source of happiness and joy."

Both sisters said that, tellingly, those who experienced war firsthand are often the ones who were less prone to make declarations against those on the other side of the war — and perhaps better able to forgive one-time enemies.

"People who experienced trauma had to 'work spiritually to find the solution in faith' " — and that includes sisters, said Ralbovsky.

Those who suffered in the war experienced something like spiritual awakening, Ralbovsky said. "They had to process that pain."

Sr. Franciska Molnar, 68, a member of the Sisters of Mercy of the Holy Cross, ministers at the congregation's home convent in Đakovo, a city about 35 miles west of Vukovar. She says she has been able to forgive the killers of her brother Saša, who perished during the Croatian Homeland War. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

Sisters aren't the only ones who believe that sisters in conflict zones have had to fully live their consecration.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Franciscan Fr. Svetozar Kraljević said sisters were "surrounded by death all of the time," but showed steadfast commitment, care and courage. "Whatever life brings," he said, "the sisters are there."

From another angle, Sr. Franka Bagarić, the provincial superior of the school sisters of St. Francis of Christ the King in Mostar, Bosnia, a city that was largely destroyed in the Bosnian war, said the conflict there prompted residents to become hyper-sensitive to religious and ethnic identities — Muslim (Bosnian), Catholic (Croatian) and Orthodox (Serbian). But it also prompted an awareness of a shared communal identity "found in wounds and suffering."

If that brought some, including sisters, to a deeper spirituality, perhaps "that can do good" to the healing of the nation, she said.

"The wounds are still deep," she said. "We still need a lot of years of healing and goodwill. Every side needs to give herself to peace."

And sisters themselves need to affirm that, wherever the travails of war and conflict occur, they must act with courage and hope and remain in solidarity with those most suffering.

Sr. Tihomira Parlaj is a member of the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul of Zagreb who helps coordinate a soup kitchen in the Croatian capital. Asked about advice for sisters in current and future conflict zones, she said: "Stay with the people, know who they are, be close to them and support the people with the needs they have." (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

Sr. Tihomira Parlaj is a member of the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul of Zagreb who helps coordinate a soup kitchen in the Croatian capital. Asked about advice for sisters in current and future conflict zones, she said: "Stay with the people, know who they are, be close to them and support the people with the needs they have."

Up to God 'to render justice and judgment'

One sister who never failed in her calling when people needed her is Sr. Damira Biškup, also a member of the Sisters of Mercy of the Holy Cross.

Biškup, 88, a trained nurse, served 25 years at the maternal wing of Vukovar hospital, and stayed there through Vukovar's fall. "We were surrounded by enemies," she recalled, and struggled with a lack of electricity, food and water — what little food came in was due to the assistance of humanitarian groups.

Sr. Tihomira Parlaj, a member of the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul of Zagreb who helps coordinate a soup kitchen in the Croatian capital, is seen here with some of those the kitchen serves. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

While Biškup was not directly threatened with violence, she recalls having to run quickly from the hospital to the nearby convent where she lived, seeing numerous bodies on the streets. "It was very difficult to witness that," she said.

She and four other sisters were able to leave Vukovar two days after the city's fall on Nov. 18, 1991, headed eventually to Zagreb, taking with them a premature infant girl Biškup carried in her arms — the girl's mother couldn't stay in the hospital during the siege.

"She was very fragile," Biškup said of the girl, born three months premature. "She needed care."

The memorial at the National Memorial Cemetery in Vukovar, Croatia, commemorates the victims of the Croatian War of Independence, called the Homeland War by Croatians. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

A later televised news conference attended by Biškup and the girl eventually helped reunite the infant and her mother. Biškup remains in touch with both the girl, Tanja Šimić, and her mother, Anka — an enduring connection celebrated in Croatian newspapers during 25th anniversary commemorations in 2016 of the events in Vukovar.

She recalls good relations before the war with Serbian doctors at the hospital. She also cherishes memories of small gestures like the Serbian driver leaving the heat on in the bus that took the sisters, the infant and other children overnight to Serbia before heading back to Croatia.

"He was sensitive to the needs of the little babies and children," Biškup said, brightening to the memory.

Sr. Damira Biškup, a member of the Sisters of Mercy of the Holy Cross, served 25 years at the maternal wing of Vukovar hospital, and stayed there through Vukovar's fall in 1991. She reads from a book of poetry published in 2019 that focuses on the Croatian War of Independence. (GSR Photo/Chris Herlinger)

Such kindness animates some of her reflections, as does her belief that Croatia is imbued with a deep collective faith. But equally importantly is her own deepening of faith — all of which Biškup reflects on in a 2019 collection of poetry whose title translates roughly into Faith in a Context Without Hope.

The book of 30 poems, compiled and released by a non-religious publisher, is dedicated to Tanja Šimić.

"Nothing now is as it was during the war, nothing as intense," she said, but adds that it is her hope that the Croatian people will never forget the events of Vukovar.

At the end of a quiet Thursday afternoon at her congregation's convent in Zagreb, with the setting sun visible through a window, Biškup read from the book, explaining through a translator that one of the poems, "Procession of Memories" affirmed the centrality of Vukovar to Croatian identity.

Advertisement

As for how she has recovered from those times, Biškup said her poetry has helped her find her way, as has affirmation of forgiveness. "We have to forgive because we're Christians," she said, adding though, "we should leave it to God to render justice and judgment."

Biškup paused, and reflected on what remains for those who suffered in ways large and small during the wars of 30 years ago.

"Forgive, yes," she said. "But forget, no."