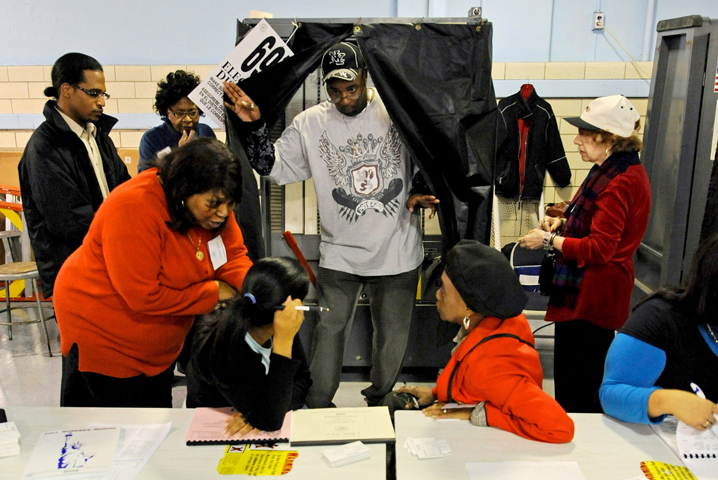

James Waitemon exits a voting booth in New York City after voting in the presidential election, in a CNS 2008 file photo. (CNS/Peter Foley, EPA)

The race is heating up.

In just under a year, the country will elect a new president. It will be the first U.S. presidential election since Jorge Mario Bergoglio became Pope Francis. No doubt, many will wonder about his "effect" on American Catholics, who are traditionally thought of as a bellwether vote.

But in asking pollsters and political pros which way the "Catholic vote" will go in 2016, some say no such thing exists. "Catholic vote," they ask, "what Catholic vote?"

"I'm not a great believer that there is a Catholic vote," said pollster John Zogby.

"Being Catholic is not a principal identifier," he said. "If you take Catholics, the profile is: white, Latino. By social class they dovetail with that white working class voter to some degree in some areas, but then, they're all over the place financially."

"Am I Catholic and a member of the NRA?" Zogby asked. "Am I Catholic and a union member? Am I a Catholic who lives in the Northeast?"

The political, cultural, regional and socioeconomic fault lines that divide much of the country shoot straight though American Catholicism itself, in other words.

There used to be a "Catholic vote" -- think John F. Kennedy era America -- but not anymore, said Kyle Kondik, managing editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball, a political newsletter run out of the University of Virginia Center for Politics.

"I think that Catholics have become kind of immersed in the general electorate in such a way that their being Catholic doesn't really tell you much about how they might vote," he said.

Kondik called the relationship between a person's Catholicism and their politics "incidental."

"It's like, why are Hispanic Catholics more democratic than white Catholics? Well, because Hispanics are more democratic than whites."

Gregory A. Smith, associate director of research at Pew Research Center, agreed: "Catholics do not vote as a bloc."

"Not all Catholics agree with the teachings of the church," he said. "Sometimes you'll hear people talk, or read things that imply that candidates who are opposed to abortion will be appealing to Catholics. Or candidates who oppose same-sex marriage will be appealing to Catholic voters. Or candidates who oppose the death penalty will be appealing to Catholic voters. Or candidates who favor more government assistance to the poor will be appealing to Catholic voters. And that's just not always the case."

Catholic thought runs the ideological and political gamut, Smith said, disparate groups of U.S. Catholic hang in different parts of the cafeteria.

Within the identifiable "subgroups" that exist, he said, "especially among white Catholics, we can look at those who attend Mass regularly and those who do not, for example, and we often see some important distinctions. If we just look at the 2014 data, among white Catholics who attend Mass at least once a week, 39 percent identify with the GOP. By comparison, among white Catholics who attend Mass less than once a week, just 27 percent describe themselves as Republicans."

Sociologist William D'Antonio, who studies U.S. Catholic beliefs and attitudes, believes Catholic subgroups can be defined much more broadly.

"It depends on what kinds of questions you are going to ask," he said. "I think the Catholic vote is pretty closely divided. Within the Paul Ryan group … it's subsidiary without any larger vision. It's reaching out, devoting maybe a couple hours a week, working in a soup kitchen two or three times a week. … Moral responsibility is at the local level. It starts with family, then the parish, then the neighborhood -- that sort of thing."

"Now, on the other side, I think [Democratic Sen.] Dick Durbin of Illinois is exemplary of the broader vision," or the "Pope Francis" vision, said D'Antonio, a Fellow of the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies at the Catholic University of America.

"With [U.S. Rep.] Rosa DeLauro, it's clear," he said. "She's written and said so many times that she carries the church's teaching and sees it in a very broad light: you have a responsibility and if it doesn't work in the family and at the level of the local government, then you go to the next level. You just can't say, 'Oh those poor people out there.' "

"These are the two ideal types," D'Antonio said.

Of course, these types also exist in the mainstream. Lots of U.S. Catholics say they like the "broader vision" championed by Francis, for example. But are they actually doing anything about it?

"Honestly, I don't know," DeLauro, a Democrat from Connecticut, told NCR. "I think [Francis] has a real impact on Catholics, but I have no idea how that translates politically."

It all depends on the issue, said Kristen Day, executive director of Democrats for Life of America, an advocacy nonprofit that seeks to elect pro-life Democrats on the issues of euthanasia, capital punishment and abortion.

"The Democratic Party is more in line with Catholic values than the Republican Party," said Day, who is Catholic, "such as supporting the minimum wage and government responsibility to help the poor. Yet, Catholics are leaning towards the Republicans because of the pro-life [abortion] issue, and these Planned Parenthood videos."

"I think when you come down to it," she said, the issue of abortion is "so important to many that they will vote against even their own best interests."

But back to Kondik and Smith's point, plenty of pro-choice Catholics also exist.

"There are lots of Catholics who support legal abortion," said Smith, "lots of Catholics who support same-sex marriage, and so on."

"Let's say the Democratic presidential nominee decided that he or she wanted to win Catholics," said Kondik. "Would they become anti-abortion rights in order to do that? Of course not. Because they would be alienating their base, and frankly they'd probably be alienating a lot of the Catholics who otherwise would vote for them."

The question of the "Catholic vote" is "muddled, definitely muddled," said Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell, executive director of NETWORK, a social justice lobby.

"I don't think either party can count on Catholics," she said.

Campbell, who tours the country with Nuns on the Bus, an annual cross-country trip that brings attention to social justice issues, said that a sense of precariousness defines much of the electorate at large, including U.S. Catholics.

Many "folks are really worried about an economy that's basically stagnant, about jobs that have disappeared," she said, "aware of flat wages, no benefits, not fixing immigration, and not feeling really anything from the candidates -- except for Bernie Sanders -- about these issues."

Others are cynical about the state of money in politics, she said, which explains some of the appeal of Donald Trump, who plays up the notion that he "can't be bought," she said.

As for American Catholics generally, "it's all a mix," she said. "I don't see much real enthusiasm about the political process."

American Catholics "like the pope," she said, "they love how he is. But as his message trickles down to the local level, they quickly pick up the … mixed feelings on the part of clergy."

"They don't get all the connections," she said, adding: "We still have trouble with middle management. Trickle down isn't working there either."

[Vinnie Rotondaro is NCR national correspondent. His email address is vrotondaro@ncronline.org.]