Famed Jesuit theologian Fr. Karl Rahner once said of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) that it marked the emergence of Catholicism as a "world church," no longer tied primarily to Europe or the West. Cardinal Francis George of Chicago asserted Wednesday evening that the late 20th and early 21st centuries have lent "empirical reality" to Rahner's claim.

"There are now local churches in every part of the world, and the hierarchy is being transformed by members from Africa, Asia and Latin America," George said during a conference in Chicago sponsored by the Catholic Theological Union and DePaul University. "What was once known as the 'Third World' is now a source of life and renewal for the church elsewhere."

Catholic demography certainly bears George out. In 1900, just twenty-five percent of the 266 million Catholics in the world lived in Africa, Asia and Latin America; by 2000, sixty-six percent of 1.1 billion Catholics lived in the global South, and by 2050, the Southern share is projected to be seventy-five percent, or three-quarters of all the Catholics on the planet. That's perhaps the most rapid, most sweeping, transformation of the Catholic population in more than 2,000 years of history.

Trying to think through the implications of what being a "world church" means, especially for the social teaching of Catholicism, was the motive force behind the Oct. 29-31 gathering at CTU and DePaul, titled "Transformed by Hope: Building a Catholic Social Theology for the Americas." There were lots of cooks in the kitchen, but much of the vision and organizing work for the conference was supplied by Carmen Nanko-Fernández, a Latina theologian at CTU and director of the Certificate in Pastoral Studies, and also Peter Casarella of DePaul.

In the interests of full disclosure, I was a speaker at Friday's closing session. Prior to that, however, I had my reporter's hat on for what proved to be a fascinating experience - though, to be sure, there were a few notes struck along the way certain to stir debate in broader Catholic circles.

* * *

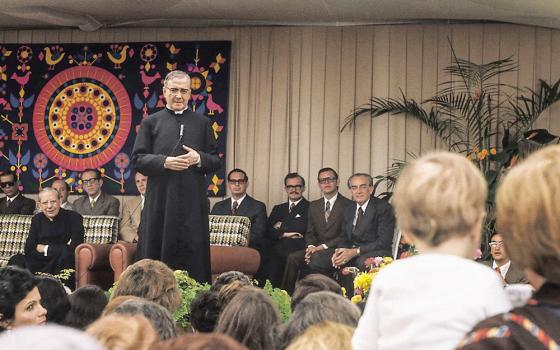

The star attraction was Dominican Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez, a Peruvian thinker and activist who is the widely acknowledged father of liberation theology in Latin America, a theological movement designed to think through the theological and social implications of Christ's own poverty. (For the record, Gutiérrez said he's uncomfortable with being called the movement's "father," saying he'd rather be thought of as one of its "nephews.")

In his remarks Thursday morning before a packed auditorium at DePaul, Gutiérrez focused on two landmark meetings of the Latin American bishops: Medell'n, Colombia, in 1968, which first gave rise to the concept (if not yet to the precise phrase) of a "preferential option for the poor"; and the 2007 assembly in Aparecida, Brazil, which affirmed and consolidated that option, along with the broader legacy of liberation theology, following decades of controversy, acrimony, and official ambivalence.

The breakthrough at Medell'n, Gutiérrez said, was shaped by two basic streams in Latin America during the 1960s: social and political upheaval, especially tension between authoritarian governments and the "eruption of the poor" as a political force; and post-Vatican II ferment in the Catholic church.

Gutiérrez said Pope John XXIII had three basic intuitions with regard to the council: openness to the modern world; the quest for unity, especially Christian unity; and the idea that Catholicism should be "the church of everyone, and especially the church of the poor." The first two points, Gutiérrez said, were developed at the council, but not so much the third.

That, he said, was the contribution of Medell'n.

Though Gutiérrez didn't make the point, it's worth recalling that post-Medell'n battles over liberation theology, both in Latin America and throughout the global church, spawned some of the most painful chapters of recent Catholic history. Then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, became a household name through his public warnings that some strains of liberation theology veered toward a this-worldly concept of salvation, as well as a Marxist understanding of class struggle that pitted a popular "church from below" against the hierarchy.

On the basis of such reservations, Catholic officialdom often took an arm's-length approach both to liberation theology and to the theologians behind it; Gutiérrez himself was the object of doctrinal investigations, both by the Peruvian bishops and by Rome. (In the end, those inquests came to a close after Gutiérrez penned an article on communion in the church deemed acceptable by both the Vatican and the Peruvian bishops.)

Given such pressures, observers have from time to time pronounced liberation theology "dead." Even the late Pope John Paul II, during a 1996 voyage to Latin America, said that after the collapse of Communism in Europe, liberation had "fallen a little, too."

It was against that backdrop that liberation theologians across Latin America took the Aparecida gathering in May 2007 as a triumphant vindication of their basic instincts. During his opening address, Benedict XVI himself said: "The preferential option for the poor is implicit in the Christological faith in the God who became poor for us, so as to enrich us with his poverty."

Gutiérrez said the results from Aparecida represent a consolidation of "the best of the theological and pastoral positions of the church in Latin America."

Gutiérrez argued that perhaps the most importance feature of Aparecida is that it was informed by people who know the "daily reality of the church in Latin America," and he offered several ways that familiarity informed the meeting's conclusions:

- Paragraph 98 of the final document hails the "courageous testimony of men and women saints" -- including, pointedly, "those who are not yet canonized" -- who lived and sometimes died "for Christ, the church, and their people." Gutiérrez said the language about saints "not yet canonized" was, among other things, an indirect reference to the late Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador, who was assassinated in 1980 and who is a hero to the liberation theology movement.

- Aparecida referred to the emergence of several previously excluded social groups - such as indigenous persons, Afro-America cultures, and women - as a "kairos," meaning a time of grace, both for the church and for Latin American society.

- The "recuperation" of the "see/judge/act" method for assessing social reality, which had been adopted at Medell'n but softened at Santo Domingo.

- Work for justice was seen as an inner component of evangelization - not just an expression of it, or a consequence of it, but an internal part of what it means to evangelize.

In general, Gutiérrez argued that Aparecida represented a recovery of the "mystical" dimension of liberation theology, alongside its more familiar "prophetic" streak. The "mystical" component, he said, pivots on the Incarnation of Jesus Christ in human history - a view of God, as Gutiérrez termed it, as "Emmanuel."

Gutiérrez concluded by suggesting that while Medell'n and Aparecida generated marvelous teaching, the real trick is to put that teaching into practice.

"Hope is not synonymous with waiting," he said. "Hope is a gift, but you don't receive that gift if you're not creating resources for it."

* * *

The "Transformed by Hope" gathering was the first major undertaking of a new "Center for Global Catholicism and Inter-Cultural Theology" at DePaul. The conference was also a natural for CTU, where some fifty percent of the student body comes from outside the United States.

Organizers made a laudable effort to ensure that the theological conversation unfolded in dialogue with the church's pastors, most notably in an opening plenary session Wednesday night featuring Cardinal George as well as Archbishop James Weisgerber of Winnipeg, President of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, and Fr. Sidney Fones of the Episcopal Conference of Latin America and the Caribbean, or CELAM. (Fones represented Archbishop Raymundo Damasceno of Aparecida, president of CELAM, who was unable to attend.)

Reflecting on Medell'n, George said that it embodied an "inductive pastoral methodology," scrutinizing the "signs of the times" in light of Christian faith, which characterized both Vatican II and the 1967 encyclical of Pope Paul VI, Populorum progression. He also noted that Medell'n endorsed the "see/judge/act" method of discernment developed by Belgian Cardinal Joseph Cardijn in the early 20th century - a movement, George noted, that was very popular in Chicago Catholicism in the 1950s.

While developments in liberation theology after Medell'n which were dependent upon theories of class conflict" have been rejected by the church, George said, its "valid intuitions and fundamental truth" have also been recognized.

George argued that where Medell'n started with the socio-economic situation and moved to finding God in the poor, Aparecida begins with the "kerygma," meaning the church's proclamation about who Christ is, and then moves to a concern for justice, "though a justice rooted in charity."

"Aparecida begins with the encounter with Jesus Christ when the kerygma is proclaimed, not only as mediated in the poor or another other social phenomenon," George said. That move is essential, he argued, for any attempt to phrase the church's message in an exclusively social or political key is "condemned to sterility."

As a result, George said, Aparecida opens up naturally to concern for permanent catechesis, sacramental life, and the understanding of the church as a "community of communities."

Medell'n and subsequent developments in Latin American theology have had a "marked influence in the United States," George said, especially through the growing presence of Hispanics in the American church.

For example, George underscored the success of the base ecclesial communities across Latin America, where small groups come together for prayer, Bible study, and to employ the "see/judge/act" method in the analysis of their social situation. George said his first trip to Latin America came in 1972, in Brazil, and already it was clear the base communities would be a "far-reaching contribution of Latin America to us here in the States."

Weisgerber likewise paid tribute to Medell'n, saying that it helped the church better integrated "personal faith and social concern."

"No improvement is possible without changing the structures that sustain injustice," Weisgerber said. "But that, in turn, requires the conversion of the persons who create and sustain those structures."

Also like George, Weisgerber suggested that Medell'n and liberation theology have had a deep impact on the social consciousness of the church. As one illustration, Weisgerber said that a keyword search of official church documents from Latin America and North America over the last 20 years reveals that "poverty" is the second most frequent in the former and the eighth most common in the latter. He also said that when the Canadian bishops recently established a set of priorities for social affairs, the fight against poverty was at the top of the list.

Fones, a member of the Schoenstatt Fathers, noted as one fruit of Medell'n that the executive officers of CELAM have had annual meetings with their opposite numbers from the United States and Canada for the last 36 years. In recent years, he said, the realities of widespread immigration from Latin America to the United States have accelerated this cooperation.

"Sadly, immigration is often marked by insecurity, injustices, tragedy and pain, including death." Yet it is also, Fones said, "a time of grace."

Fones pointed to three social phenomena in Latin America today -- globalization, post-modernism, and growing cultural and religious pluralism -- all of which, he said, at times have the effect of both "aggravating and redefining poverty."

Moreover, Fones said, the church too faces steep challenges in today's Latin America.

"In many groups in Latin American society, there is a certain hostility to the church," he said. "Within the church itself there's what we call a 'white schism,' meaning an insufficient and weak identification with the magisterium and the structures of the church."

In that light, Fones said, the challenge taken up by Aparecida, to "start anew from Christ," is especially timely. He suggested a high-tech paraphrase for the spirit of Aparecida: to "reboot" the church and the faith.

Among other things, Fones said, that means overcoming the internal divisions in the church that sometimes marked post- Medell'n debates over liberation theology and the broader direction of the church.

"Those who plea for defense of marriage and the family should make the same plea for immigrants," he said. "Those who demand social justice should also demand justice for the unborn."

Finally, Fones applauded the determination at Aparecida to listen to the laity. Among other things, he cited a paragraph in the final document calling males in Latin America to take greater responsibility within their families - a first in a magisterial document in Latin America he said, and it was written by a lay woman.

Summing up Aparecida's call to "permanent mission," Fones said its implicit social philosophy is that "the more Christian society becomes, the more human it will become."

* * *

As a public speaker, George has a habit - which is either charming or maddening, depending upon how one chooses to look at it - of dropping in fascinating or provocative comments almost as marginalia alongside his main lines of thought, without really developing them completely.

For example, Wednesday night he offered the intriguing claim that for Pope John Paul II, "culture" was as fundamental a theological concept as "nature" and "grace." Time, unfortunately, did not permit anyone to ask him to expand.

At another point, George reminisced about the 1997 Synod for America in Rome, which brought together bishops from North America and Latin America. The major discovery, he said, was that unity was not something they had to work to achieve, but rather something that was already there in principle, waiting to be developed in practice.

Again as an obiter dictum, George said the only real division at the synod was over economic philosophy, with the Latin Americans taking a much tougher line on global free-market capitalism or, as they typically call it, "neo-liberalism."

This time, however, someone in the audience was ready with a follow-up. Daniel Finn, who teaches both theology and economics at St. John's University in Collegeville, Minnesota, and who is also a past president of the Catholic Theological Society of America, asked George if the recent financial crisis in the United States and around the world has had any impact on those assessments.

George said it's too early to tell what most bishops are thinking, but he summed up his own thoughts this way: "During the synod, the Latin Americans said [the neo-liberal system] didn't work for them. What we're now seeing is that it doesn't work in itself."

George then offered largely the same answer he gave me during a recent interview in Rome, the gist of which was that an exaggerated laissez-faire approach to the market presumes a "flawed anthropology," meaning an overly individualistic reading , and that the world appears to be headed towards a slightly more "managed" approach to economic affairs.

* * *

Another interesting moment during the conference came Wednesday night, when a member of the audience at CTU rose to ask about the relationship between the "listening church" and the "teaching church" - the ecclesia audiens and the ecclesia docens.

Fones echoed the premise of the question, saying it's important for "lay people to take part in the decisions of the church." Fones said lay initiatives and leadership should not be understood exclusively as "out there" in the world, but also inside the church.

"The ecclesia docens and audiens cannot be sharply distinguished anymore," Fones said.

George then took the floor, saying that while he agreed with the need to listen, ultimately bishops still have the responsibility to teach.

"Bishops speak for the faith, not always for the faithful," he said.

George said that bishops are accountable to "the tradition that unites us to the apostolic faith," which means that sometimes they must challenge "trends in the culture which are always evangelically ambiguous."

"In this culture, for example, you can often get majorities that disagree with the church on particular points, especially about sex. It doesn't take a great deal of courage in this culture to step forward and say, 'I agree with that,'" George said. "The New York Times will support you, calling it a brave thing to say."

"It takes courage to challenge that," George said. "Discernment of whether something is truly of the Lord is the bishop's job. You have to listen for a long time, but ultimately it's up to the bishops to make that judgment."

* * *

A series of breakout sessions during the conference wrestled with various challenges facing Catholic social theology.

On Thursday morning, for example, Patrick McCormick of the Jesuit-run Gonzaga University in Spokane, Wash., made the provocative argument that the United States is an overwhelmingly Christian society that is nevertheless "extraordinarily un-Christ-like" in important respects. He called America a "violent and punitive" society, which is also "strikingly unequal and ungenerous" in its social policies, such as the percentage of the federal budget devoted to overseas development aid.

McCormick argued that four aspects of contemporary American culture prevent religion from playing a "transformative" role": religious illiteracy, consumerism, individualism, and an apocalyptic streak in American Christianity.

In the religious domain, he said, consumerism leads people to think of culture as just one more commodity -- like a CD blending reggae, soul, tejano, rap, and country/western. Treating cultural values and concepts that way, McCormick said, ignores the history and tradition behind them.

Likewise, individualism is reflected in the growing tendency of American Christians to affiliate not with any global communion, but independent denominations and congregations which are focused entirely on the tastes and interests of the local community.

"In a sense, what we have is a listening church run amuck," McCormick joked.

The end result, McCormick asserted, is a tendency among many religious believers towards an "uncritical embrace of U.S. militarism and imperialism."

In another session, Milagros Peña of the University of Florida shared her experience of working with immigrants in border areas. At one point, an audience member asked her a hard question: Since the majority of U.S. Border Patrol agents are now Hispanics and thus, presumably, largely Catholic, does Peña believe they should refuse to enforce laws that voices in the church perceive as harsh and punitive?

Peña didn't flinch: "If they take their faith tradition seriously, then that would be something they're being called to do," she said.

Pressed as to how the United States could cope with the completely open border that would result, Peña said we're already there.

"In effect, we've got an open border right now, and unless you address the underlying reasons for that, it won't change," she said. "All we're doing now is making crossing uglier and more costly."

There was little dissent from either analysis during the break-out sessions, though it goes without saying that both would certainly kick up dust in broader Catholic circles.

* * *

St. John's Seminary in Camarillo, California, is famous for the cohort it produced that included no fewer than five future episcopal heavyweights: Cardinals Roger Mahony of Los Angeles, Justin Rigali of Philadelphia, and William Levada of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, as well as Archbishop George Niederauer of San Francisco and Bishop Tod Brown of Orange.

In the wake of the CTU/DePaul conference, we may need to add the University of Ottawa in Canada to the list of factories of future Catholic luminaries. Archbishop James Weisgerber of Winnipeg revealed that he and Cardinal Francis George studied there together in the 1960s; both men are today the presidents of their respective national conferences of bishops.

Weisgerber added one further tidbit, which is that he and George studied alongside another future eminence, though this time definitely not of the ecclesiastical sort - Alex Trebek, host of the popular TV game show "Jeopardy."

Those who know George's encyclopedic mind might want to suggest that he ring up his old classmate, and try his hand at "Jeopardy" - he'd probably do quite well, and in any event, it's hard to imagine a more intriguing example of evangelizing culture.

The e-mail address for John L. Allen Jr. is jallen@ncronline.org