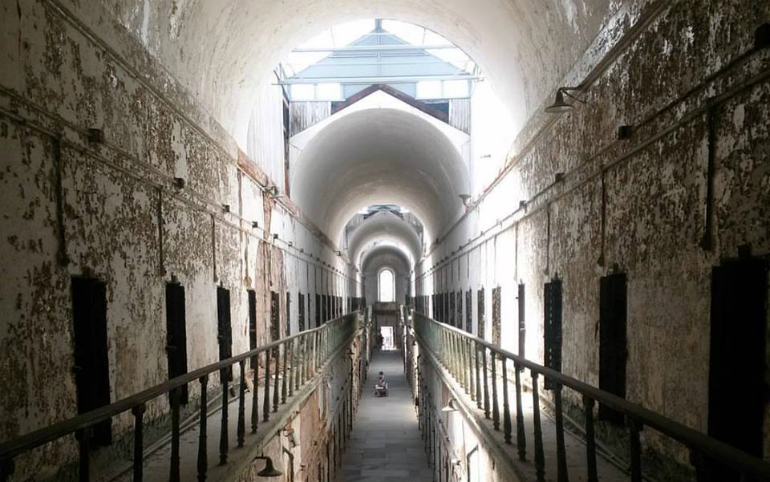

A view inside of Eastern State Penitentiary, cell block 7. (Mariam Williams)

I recently found myself once again thinking about the relationship between churches and prison. This time it was a after a visit to Eastern State Penitentiary, an historic site considered the first prison in the world designed to make convicted criminals penitent for their actions.

Before this visit, I hadn't noticed the root of the word "penitentiary." Eastern State's architect invested so wholeheartedly in the concept of penitence that he designed the prison to resemble a cathedral. The cell blocks abound with archways and vaulted ceilings. A sky light in individual cells represented the eye of God. And like cathedrals I've visited, the design is awe-inspiring.

How is a church like prison and being incarcerated like belonging to a church? And should they be alike? I pondered these questions as I walked the non-air-conditioned cell blocks and grounds on a day when the outdoor heat index was in the upper 90s.

I think now that both prisons and churches (systems, not particular buildings) should call people to recognize their wrongs and turn from them. Repentance is, after all, essential to Christ's message, and rehabilitation is (allegedly) one of the main purposes of modern-day prisons. But I also found similarities between churches and prisons in some ways I didn't expect, such as how both expect people to control their sexuality, possibly to infinity.

Discussion of sexuality at the site of a former prison was a surprise to me. In fact, it's supposed to be kept somewhat hidden; while the topic of sexuality is listed among the audio tour stops in Eastern State's map, its corresponding stop numbers are not, which means visitors have to put forth some effort to find the stop numbers and hear them. (This helps protect children who might be taking the audio tour from hearing adult content.)

Once I located the stop numbers, I heard, among other stories, evidence of Eastern State administrators' efforts to stop prisoners from engaging in masturbation in the 19th century and about their willingness in the 20th century to ask new inmates at intake how they planned to handle their sexual urges for the next 10 to 50 years or so.

How do you plan to handle potentially lifelong, involuntary celibacy? It's a question I've never had anyone in church leadership or a layperson in a heart-to-heart discussion ask me that directly, because it is never assumed that a heterosexual woman, and even more specifically a heterosexual black woman who is an active church member will be single forever -- even though abstinence until marriage is still taught and to some degree expected; even though such black women are still expected and often themselves demand to marry a churchgoing, Christian man; and even though women of all races far outnumber men in churches in all denominations.

And yes, while researchers have debunked the myth that 42 percent of black women never marry, anecdotal evidence remains strong that educational and income disparities, living in large cities, mass incarceration and even internalized preferences for Eurocentric beauty standards all pose challenges to black women who want to marry, and especially to those who want to marry black, churchgoing Christian men.

I probably wouldn't have made this connection if many of my recent social media time lines and news feeds hadn't been filled with discussion about the challenges of being single, the specific challenges of being single, black, Christian and female and criticism of the purity industry capitalizing off a demographic's loneliness and frustrations. But those articles and blog posts have appeared, and so I've thought about the last time I asked a church friend how she was deterring sexual urges (including the urge to commit Eastern State inmates' notorious offense, masturbation). Both my friend and I were 24 then. We're both 36 now. She's married. I'm not. It doesn't look like marriage will happen for me within the next year, and given the rise in the average age of first marriage, I know my situation is not unusual.

But I might be unusual for suggesting that church leaders, who teach, counsel and preach to a flock, face the reality of lifelong singleness for black women and how unrealistic and unfair the expectation of lifelong celibacy is within that, well, sentence.

Some people choose a life of singleness and celibacy in favor of total devotion to the Lord. But involuntary singleness too often feels like punishment and penitence, like you did something wrong and are now meant to sit alone for a long period of time and reflect on all your faults and insufficiencies, and then, by looking into the eye of God, find repentance and rehabilitation, until one day you are released, welcomed back into the society of People Who Did Things The Right Way, and found to be worthy of someone's promise of eternal love and devotion.

The truth is, there are no perfect people, there are no formulas for changing yourself or your life to attract "the one," and sometimes, often, what we really want for our lives just doesn't happen. While self-improvement is something everyone can benefit from, no one should be made to feel bad for what's out of their control, or made to feel evil for doing something to relieve their loneliness -- particularly when they've been given an unexpected and indefinite sentence.

[Mariam Williams is a Kentucky writer living in Philadelphia and pursuing an MFA in creative writing at Rutgers University-Camden. She is a contributor to the anthology Faithfully Feminist and blogs at RedboneAfropuff.com. Follow her on Twitter: @missmariamw.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Mariam Williams' column, At the Intersection, is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.