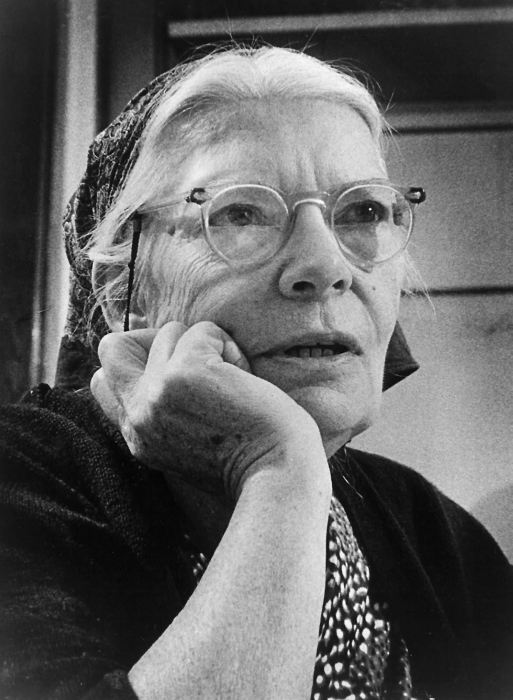

Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement. (CNS photo/courtesy Milwaukee Journal)

"When one mentions Dorothy Day, one thinks automatically of the Catholic Worker Movement, the religious organization that she founded to help alleviate poverty and injustice. But few people know that Dorothy Day was also a committed suffragist who endured torture and mistreatment at the hands of the jailors in Occoquan Prison in Virginia after being arrested for picketing the White House." So said the Long Island Woman Suffrage Association when they proclaimed her "Suffragist of the Month."

Her arrest in 1917 with suffragists outside the White House and the brutal treatment she and others endured at the Occoquan workhouse -- it is reported that for her noncompliance Day was lifted and slammed down over an iron bench -- was a turning point in her own life as much as it was a turning point in the struggle for women's suffrage.

After the women went on a hunger strike of 10 days, President Woodrow Wilson personally ordered their release and subsequently announced his support for the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote, which was passed by Congress less than two years later.

In recent years, the heroism and sacrifice of these courageous women have been featured in documentary films, books and countless articles. Their memories are especially invoked during the run ups to presidential elections to encourage voter turnout. One article from 2012, "Lucy Burns, A Look at a Catholic American Suffragette," by Michele Stopera Freyhauf, cites Day's contributions to the struggle and insists that "it is imperative for all women to make their voices heard this year by casting a vote. To turn a blind eye to these issues diminishes the sacrifices our foremothers made for us. To not cast a vote takes away your voice, makes you a silent bystander."

If Day can be described as "a committed suffragist," then it might also be admitted that by the standards of some of those who would honor her memory by going to the polls, she was also a "silent bystander" who diminished her own sacrifices by never voting.

"I went to jail in Washington, upholding the rights of political prisoners," Day wrote in a June 1967 column in The Catholic Worker. "An anarchist then as I am now, I have never used the vote that the women won by their demonstrations before the White House during that period."

How did an anarchist end up in jail with a bunch of suffragists? In November 1917, Day was 20 years old and already an experienced journalist. She was on the staff of the socialist journal The Masses when it was shut down by the U.S. government, so she had time on her hands.

Her friend Peggy Baird, just released from a 30-day jail sentence for an earlier White House protest, invited her along to another. "I don't see why I shouldn't go," Day responded. "I hate not to be working, and I don't see what else there is I can do right now." For Day and her friend, it was the right of people to protest and the rights of prisoners that motivated them, not a hunger for the vote.

"I wouldn't use the vote if I had it," Baird said, "but that doesn't keep me from joining them when they're making such a good fight."

Her experience at the Occoquan Prison gave Day a sense of solidarity and identification with the poor and the prisoner that never left her.

"I lost all consciousness of any cause" she wrote in her 1952 autobiography, The Long Loneliness. "I could only feel darkness and desolation all around me. That I would be free again after thirty days meant nothing to me. I would never be free again, never free when I knew that behind bars all over the world there are women and men, young girls and boys, suffering constraint, punishment, isolation and hardship for crimes of which all of us are guilty. ... People sold themselves for jobs, for the pay check, and if they received a high enough price, they were honored. If their cheating, their theft, their lie, were of colossal proportions, if it were successful, they met with praise, not blame."

The reluctance of Day and other anarchists to vote is sometimes misread as a reluctance to be involved in civic affairs, but the focal question asks how to best involve oneself. For Day, the answer was not found at the ballot box. It is no contradiction that Day and the newspaper she published supported the voting rights of African-Americans.

In a November 1956 column, Day wrote "even though the editors of The Catholic Worker do not believe in the vote, in elections as conducted today, we do agree that man [sic] wants a part to play, a voice to speak in his community, and this is usually exemplified by the vote." Day held that everyone should have an equal right to speak, an equal part to play in her or his community and an equal right to vote or not to vote.

Some suggest that in her last years, Day's positions on anarchism and voting softened. The last word we have from her on voting is a diary entry dated August 25, 1980, three months before her death. "'All Creatures Great and Small on TV,' followed by a woman's rights program (the anniversary of woman's suffrage) about Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. I went to jail in Washington, D.C. for woman's suffrage in the fall of 1917, but I have never voted."

"I have never voted." Day repeated these and words like them several times in her last years without elaboration. One friend who knew Day better than I did says that he senses in these words a tone of regret, of missed opportunities.

I hear something else altogether. I believe that Day was expressing satisfaction for a life well-lived, for faithfulness to holding to an ideal against years of adversity. It cannot have been easy for her, as it is not easy now. I know from experience that a principled refusal to vote is easily misunderstood and that even the best of friends on a political bandwagon can be callous and sometimes incredibly cruel to those who will not jump on.

As Day's cause for sainthood progresses, her name is better known, but sometimes I fear who she really was gets lost in the public perception. A thoughtful academic and blogger, Richard Fossey, asks the question, "Who would Dorothy vote for?"

"As a Catholic, I ask myself, who should I support for President? And who would Dorothy Day vote for if she were alive today? I turn to Dorothy because she is my lodestar for how I should live in 21st century postmodern America. I think Dorothy would vote for Bernie Sanders."

Even if one could imagine Day voting, her voting to elect a president who as a senator championed the $400 billion F-36 fighter and who consistently voted to fund aggression in Afghanistan and Iraq, a candidate who when asked about the use of drones and special forces in the "war on terror" promises to use "all of that and more" if elected, is beyond the imagination.

Her anarchism has never been more relevant and vital than it is in 2016. Day's life assures us that hope is not a cynical electioneering slogan but a real human possibility. It is significant that of the four Americans whom Pope Francis commended in his address before Congress last September, one, Dorothy Day, was a woman who by deliberate choice never voted and yet had engaged with the issues of her time and had an enormous impact on her world. She did not turn a blind eye, and refusing to vote did not take away her voice.

Along with her friend and comrade in the Catholic Worker, Ammon Hennacy, Day "did not bother to choose between the rival warmongers who sought to run the country," but "voted every day practicing [her] ideals against war and the capitalist system which caused war."

"We need to overthrow," Day counseled in a September 1956 column, "this rotten, decadent, putrid industrial capitalist system," not perpetuate it with our votes. She was not bound to choose between greater and lesser evils, and neither are we. The pollsters are wrong -- our choice is not between being a silent bystander or a collaborator with one degree of evil or another. Day's anarchism is the antidote to the paralysis of those who reach the conclusion that electoral politics are a meaningless charade; it is encouragement to those tempted to abandon hope when they discover that their hope in the system was misplaced all along.

Day considered the ballot and decided that it was not worth her time. Fasting and prayer, on the other hand, she found worthwhile, along with sharing resources in community, breaking bread with the hungry and welcoming the stranger, tending gardens and engaging in daring acts of nonviolent protest. These activities constitute a practical political program that she could embrace. It is a program that, unlike the paltry and soon to be betrayed promises of the corporate political parties, holds infinite potential to bring peace and healing to this tortured planet

[Brian Terrell has been a Catholic Worker for more than 40 years. He is a former mayor of Maloy, Iowa.]