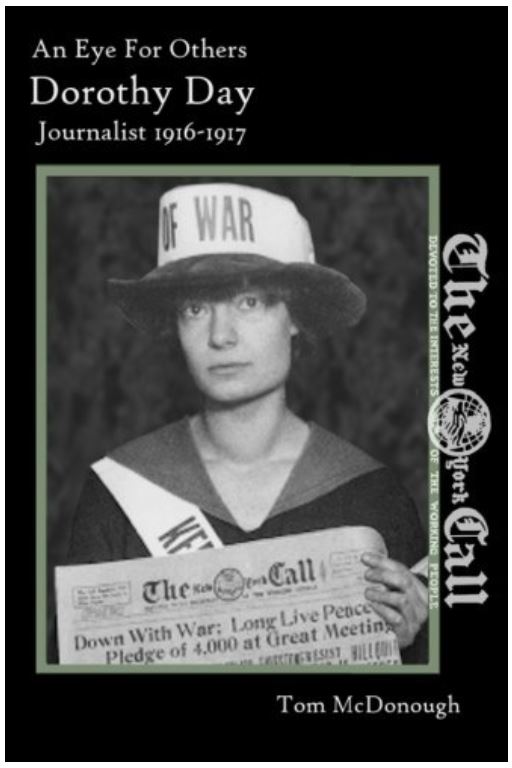

Cover artwork for "An Eye for Others" by Thomas McDonough. (Clemency Press, Washington, D.C., 2016)

Dorothy Day's books are hot items these days. Ever since Pope Francis identified her as one of four great Americans, up there with Abraham Lincoln, Dr. Martin Luther King, and Thomas Merton, popular interest in her life and writings has burgeoned. New books on Day or the Catholic Worker, the lay movement she and French itinerant Peter Maurin founded, abound.

Thomas McDonough gives us one more with An Eye for Others, a slim, invigorating work featuring articles young Day wrote for the Socialist daily, The New York Call, between the autumn of 1916 and early 1917.

The New York Call's "girl reporter" was almost 19 when she arrived in New York City, having left the University of Illinois after two years of study, determined to work for social change through journalism. Eager for employment, she convinced the editor of the struggling, leftist newspaper to hire her as a one-woman "diet squad" reporting on how one could live off of five dollars a week.

Day quickly proved her talent as a writer, garnering 36 bylines during her six months with The New York Call. She covered labor strikes, penned compelling profiles of starving tenement dwellers, reported on the New York food riots of 1917, interviewed Leon Trotsky, followed the fate of the country's first female hunger striker imprisoned for advocating birth control, and wrote of opposition to the United States' impending involvement in World War I.

McDonough provides historical context to this collection. Included here are fascinating details about the radicals and bohemians mentioned in her autobiography, The Long Loneliness, and the anti-war activism that preceded U.S. entry into World War I.

New York's Lower East Side in the early 20th century is a place of crushing poverty, protest, and energetic literary creativity. Young Day absorbed it all, reporting what she saw with intelligence, sardonic humor, and a perspective that inspires faith in our ability to work for a society where, as she would later often write, "it is easier for people to be good."

The social issues Dorothy covered 100 years ago are astonishingly relevant for us today. Income inequality, the scandalous lack of a living wage, the prioritizing of national security interests (i.e. war-making) over human need are all there, perhaps in more acute form. According to McDonough, the cost of food for the average American family increased 74 percent between 1914-1916, while union wages rose only 9 percent.

Even at 19, Dorothy could articulate a fierce dissent from the cruelties of the status quo without lapsing into despair or cynicism. Describing the ravages of poverty unsparingly, she still noticed beauty and human tenderness in the most desperate corners of human existence.

Her lively dispatches for The New York Call reflect the exuberances of the times. "Sumthin' and "gee" pepper her prose, but there is nothing superficial about the curiosity of this young woman who, by her own account, had a habit of stopping to look at people to "wonder and wonder about their lives," how they "got through every day."

"The Short and Simple Annals of the Poor are Slow Starvation," reads the headline of an article written in November 1916. Another begins:

Walk up five flights of stairs of the dirtiest and the oldest house on 2d street, past the dirty barber shop on the ground floor, where the two barbers play, for lack of something better to do, on the mandolin and banjo; past the first floor, where a prolific woman with no figure sits surrounded by her brood all day and finishes pants; past the room on the third floor where another woman sits and sews and never looks up, because there is nothing to look at; past the room on the fourth floor, where the little Italian woman bursts into song now and then, forgetting herself and her sorrows when she looks at that clouds that are tinted like the breast of a dove; and then up to the top floor, where the rooms are cheaper.

The New York Call reporter walked up many a stinking, tenement stairwell to listen and write as mothers described their tedious struggle to stave off their children's hunger. Many of her accounts read like a documentary film, the camera catching the expression of the toddler "gone batty" from malnutrition and how the "little girl of twelve" scrubbed the kitchen clean except for the patch beneath the cot where her ailing father lay, so as not to disturb him.

Faith is implicit in Day's articles even though they were written prior to her conversion to Catholicism. They bring to mind Vincent Van Gogh's charcoal sketches of the miners of Belgium's Borinage region. In their thoughtful rendering of the lives of the hidden and oppressed, writer and artist remind us, "Here, too, is an image of God." The perspective of pre-Catholic Day inclined toward Christ Incarnate, especially as he is revealed in the poor.

"We do not love concepts or ideas; we love people," Pope Francis told a gathering of leaders of popular movements in July 2015. Young Day seemed to know this implicitly and avoided flattening reality to fit an ideological lens. Numerically speaking, a person can live off $5 a week, she concluded at the end of her "diet squad" experiment, but life would be a "dull misery" of skimping along. To the 60,000 working girls of New York City, whose "cheerless" existence she too experienced, she advised squandering $1 of one's weekly wage for a down payment on a phonograph, then savoring the company the music provides.

It has been too long since I read Day's writings. They invariably stir a deep optimism within me, a peculiar reaction given her focus on life's harsh realities. Yet after reading her, I always feel working for a just order is not only life's best option, but could be a profoundly joyous venture. I felt similarly reading An Eye for Others, a wonderful antidote to that culture of indifference we are well-advised to avoid.

[Claire Schaeffer-Duffy, a freelance writer, lives and works at the Sts. Francis and Therese Catholic Worker of Worcester, Mass.]