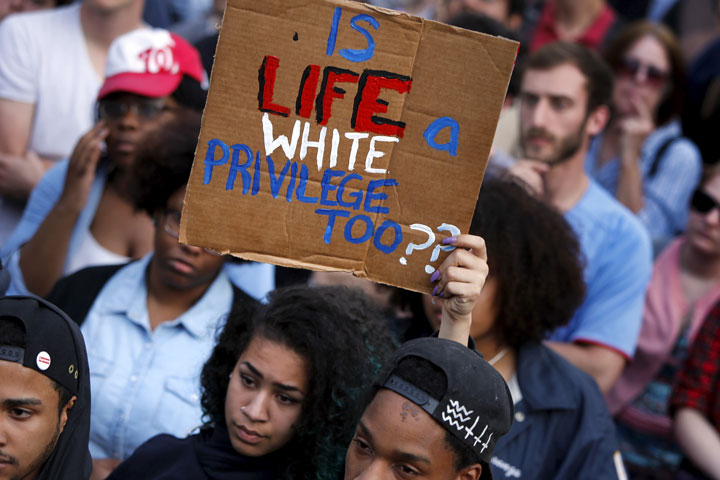

Protesters against police violence march toward the White House in Washington April 29. (Newscom/Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

BEYOND APATHY: A THEOLOGY FOR BYSTANDERS

BEYOND APATHY: A THEOLOGY FOR BYSTANDERS

By Elisabeth T. Vasko

Published by Fortress Press, $29

Elisabeth T. Vasko's challenging text, Beyond Apathy: A Theology for Bystanders, makes the case that all Christians, wittingly or not, are often a silent party to violence -- sexual violence, slut-shaming, gay-bashing, white racism, bullying, and more. As privileged bystanders, she says, we must shed our unethical passivity, acknowledge our complicity, and let our brokenness transform us.

She quotes Dorothee Sölle: "I am also responsible for the house which I did not build but in which I live." Or, in Vasko's words, "Though we may not be liable for the creation of structural injustice, we are responsible for its attenuation."

This, then, is Vasko's primary concern, and she makes a compelling case that it should be of fundamental concern to all thoughtful Christians. Unfortunately, the density of her prose may prove a challenge to nonacademic readers looking for guidance in a more easily digestible format.

Vasko draws on feminist, womanist and liberation theologies. She gives credit to theologians of color and to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community, whose interpretations of the Gospel and accepted social mores are often radically different from those of dominant white, heterosexual culture.

The recognition that such a culture exists and that members thereof profit from it -- socially and economically -- is Vasko's starting point. Whether they do so consciously or not is ultimately immaterial, although Vasko allows that most of us fall into the unconscious camp. Still, this does not excuse it -- nor should it.

"Structural violence creates social injustice. The violence that is rooted in the everyday evils of systemic and institutional oppression is harder to root out because it often escapes recognition," she writes, cutting to the heart of her argument. "Practices of social exclusion, coercion, and intimidation continue to undergird human relationality within personal, social, and institutional spheres. These practices, which often go unnamed, foster unprecedented levels of social privilege for a select few at the expense of many."

The "privileged apathy" or "passive bystanding" around which the author frames her text is, she argues, a learned behavior born of conflict avoidance and indifference to suffering other than our own, compounded by social privilege and a concept of "divine perfection that suggests that only God is good enough, powerful enough, and wise enough to offer the remedy."

Not so, says Vasko. What she proposes in response is a "theology of redemption that acknowledges human complicity in sin and, at the same time, bespeaks of the power of human agency to cooperate with God in the transformation of the world."

She indicts the tradition of Christian atonement theory as being tied to white racial privilege in its "alignment of divinity with maleness, rationality, and whiteness" and a theology in which "Jesus' body is only redemptive when it is dead, lifeless, passive, and submissive." She sees this imagery as justification for "sacrificial scapegoating, a form of victim-blaming."

She also covers white denial (of systemic oppression) and systemic ignorance (that allows racial injustice to go unchallenged), and calls for those who are "systematically privileged" to give up their self-deluding sense of innocence and face their role in perpetuating injustice.

Her interpretation of the story of the Syro-Phoenician Woman probably dives more deeply into the Gospel account than most readers will have heard in the pews. The book's intended academic audience will appreciate the exegesis, while Vasko's remarks at the chapter's conclusion about the difference between social justice (which empowers) and charity (such as monetary collections and canned food drives, which do not lead to lasting partnership) will hit closer to home for other readers.

So what is the thoughtful, concerned Christian to do? Vasko calls for eucharistic solidarity, which, "for privileged people ... involves more than self-reflection on one's own complicity in violence. The praxis of eucharistic solidarity requires outward attempts toward social solidarity, including active welcome and public advocacy."

That may include the redistribution of wealth and power, immigration reform, challenging racist theologies, opening up secular and sacred public spaces to the experience of nonwhites, and desegregating daily existence.

That kind of compassionate solidarity with the marginalized -- who, indeed, are marginalized because we have helped to make them so -- is the only course of Christian action that may lead to a world without violence, or a less violent world.

If Vasko's message is about comforting the afflicted, it is equally as much about afflicting the comfortable. That, dear privileged reader, would be you and me. In this case, as the comic strip character Pogo famously said, "We have met the enemy, and he is us."

[Julie Bourbon is editorial director at the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges.]