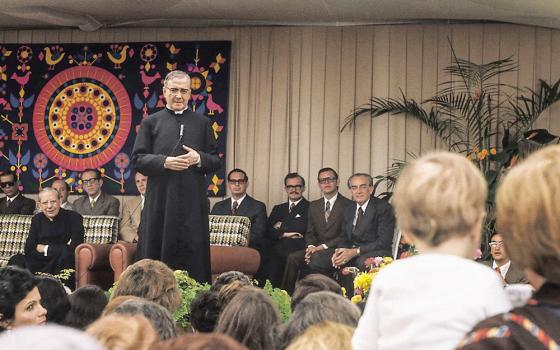

Retired Australian Auxiliary Bishop Geoffrey Robinson of Sydney (CNS)

FOR CHRIST’S SAKE: END SEXUAL ABUSE IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH ... FOR GOOD

FOR CHRIST’S SAKE: END SEXUAL ABUSE IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH ... FOR GOOD

By Bishop Geoffrey Robinson

Published by Garratt Publishing, AU$17.95

The title might lead one reasonably to expect a kind of pamphleteering campaign against abusers and a tick list of suggestions for new structures and programs to deal with abuse.

Bishop Geoffrey Robinson, however, dares something more fundamentally revolutionary in For Christ’s Sake: End Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church ... For Good. He dares to pull on the thread that unravels the cloak that has hidden the institutional disease. We all know the symptoms, of which sex abuse is the most apparent and most alarming. Robinson unwinds the thread slowly, and for the most part ignores all of the horrific particulars and incomprehensible depravities of the abuse scandal. That part of the story by now is well-documented.

Instead, like a good diagnostician who knows that understanding a disease begins with understanding the patient’s story, he performs an exacting examination of the culture out of which the abuse crisis has grown.

“There is an ancient saying ... ‘the corruption of the best is the worst,’ ” he writes in the introduction. Given the dimensions of the scandal, he says, “we can no longer limit our blame to the individuals, but must also look for factors within the very culture of the Church that have contributed. And when so many authorities in the church have attempted to conceal the abuse, or treated victims of abuse as though they were an enemy of the church, we must again look for systemic factors behind such behavior, factors that are part of the very culture of the church.”

Those lines alone are worth the book, for they cut through the unending obfuscations, excuses and rationalizations that have become the familiar hierarchical talking points.

What we all know by now is that outside forces -- state inquiries, aggressive prosecutors, victims and their advocates -- are able, with varying degrees of success, to force the details of the scandal out of the culture. All of that leads to copious apologies (though for what is never detailed), new programs to protect children, new resolves that this should never happen again.

Such steps are all to the good, but they do very little to deal with the “why” of the matter, and it is at the point of “why” that Robinson is initiating an invaluable discussion.

Pursuing the “why” leads one deep into the story, into the foundation of the institution and its very idea of God. What one finds at the bottom, despite an accompanying rich language of love, is an ever-present “angry” god, Robinson says.

“The very structure of the church, with a monarchical pope insisting on obedience and using coercive means to ensure conformity, means that the angry god is never far away. ... This has created a church in which, despite the talk of love, practice has been based too much on fear rather than love, and authorities have always had the support of the angry god for their words and actions.”

A retired auxiliary bishop of Sydney, Robinson speaks from the inside and though he may be marginalized because of his critique, he nevertheless understands the workings of the institution as well as the need for discipline and clear teaching. He also understands the distortions that can accumulate when fear becomes a primary motivation for how one behaves, as well as the disorientation that can occur when fear is removed. What holds the community together when fear no longer works?

He is not an advocate of cheap grace, even as he methodically inspects the church’s attitudes on sexual morality and the “exaggerated importance” given to such teachings. The priest “who still believes in an angry god, whose moral thinking is confused and immature, and who sees all sexual morality in terms of mortal sins directly against God,” he writes, “is living in an unhealthy culture, a culture out of which many different unhealthy actions can, and do, arise.”

Ministry can become misshapen, to the point of abuse, because of the elevated notion of ordination that has evolved over centuries, the “ontological” difference that serves to separate priests from the rest of humanity. What results is a mystique that leads to a sense of privilege and protection from accountability.

The scandal is an enormous drain on the credibility of the Catholic church and major obstacle to growth in other areas of church life. As enormously debilitating as it can be, it is a symptom of deeper maladies. To overcome the scandal, Robinson says, the church “must look at itself again from the foundations up, and that must include looking at laws and beliefs” that some might consider immutable.

[Tom Roberts is NCR editor at large. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]