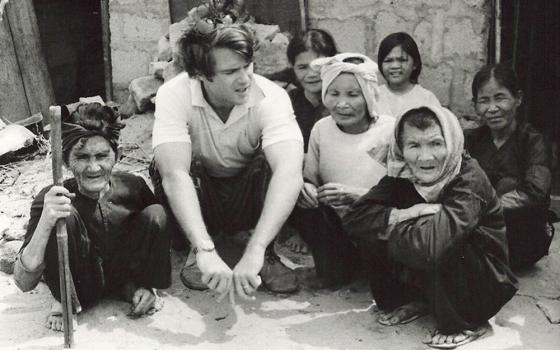

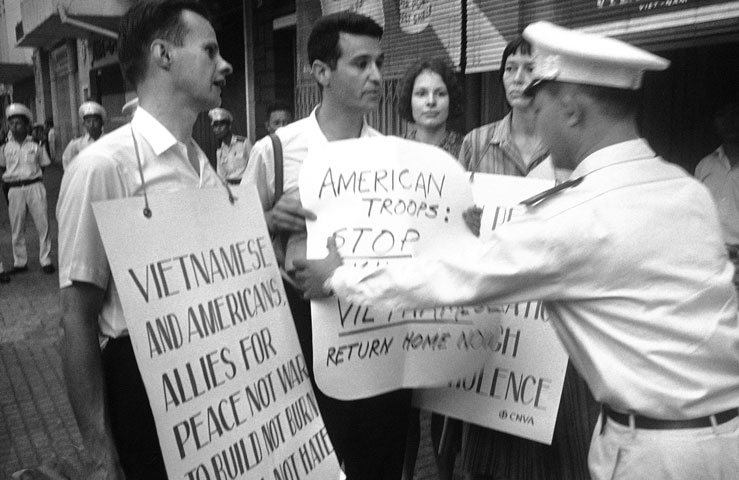

William Davidon, second from left, is stopped by a Saigon policeman in Vietnam in 1966. Davidon and other anti-war Americans were heading to demonstrate at the U.S. Embassy, but were taken to the airport for expulsion. (AP Photo)

THE BURGLARY: THE DISCOVERY OF J. EDGAR HOOVER’S SECRET FBI

THE BURGLARY: THE DISCOVERY OF J. EDGAR HOOVER’S SECRET FBI

By Betty Medsger

Published by Alfred A. Knopf, $29.95

Betty Medsger's monumental study shares two subjects: the FBI and the Catholic left anti-war movement of the Vietnam era. The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover's Secret FBI is a book she was born to write, her magnum opus, given that it is largely unprecedented in her career. Medsger began as a traditional journalist, first at the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and then at The Washington Post, but by the mid-'70s she ran off to the West Coast and the groves of academic journalism and freelancing.

It was an atypical career move, since Medsger was such a good reporter. Indeed, The Burglary is a demonstration of what establishment journalism could and did accomplish back then, as opposed to the rougher sort of new journalism that flourished during the 1970s and '80s -- Tom Wolfe, Hunter Thompson, et al.

The burglary in question was that of the office of the FBI in Media, Pa., in 1971. Medsger's book begins with its instigator, William Davidon, his biography and his connections to the new Catholic left, just then coming into prominence. The Flower City Conspiracy, draft-board raiders who were typical of the period, had broken into a suite of federal offices that included an FBI office in 1970, but they were apprehended on site. That event inspired Davidon, but he decided this time to get away, escape scot-free, which had not been the usual practice with such protesters. Other protesters had followed the example of Josephite Fr. Philip Berrigan and Jesuit Fr. Dan Berrigan, who had become the face of such actions.

Medsger also sketches the larger history of the late 1960s in America, and even today it is startling to read. Then we get the intimate story of the burglary, its participants and other parallel events, including Davidon's status as an unindicted conspirator in the case of the soon-to-be-held Harrisburg Seven trial.

A lot was going on back then. The Catholic left was the most peaceable offshoot of anti-war protesters in the Vietnam era. But, in both the public and the press's view, all such events tended to blend together, from draft-card burning trials, such as the Boston Five in 1968, to the circus-like Chicago Seven case in 1969, to the killings at Kent State in 1970.

Medsger revisits the half-century history of J. Edgar Hoover. The fated coincidence of the Media burglary in 1971 and Hoover's death in 1972 both denied the burglary its rightful place in history and paradoxically made its revelations as influential as they were, culminating in the Senate's 1975 Church Committee Report, which called for a number of reforms within the bureau. Almost none were implemented.

Medsger makes clear what a destructive figure Hoover was. At the time of the Media break-in, he was equally powerful and unstable. One hallmark of her exacting, prudent account is that Medsger never samples any personal motivations for Hoover's conduct, as a number of other authors have, citing supposed repressed homosexuality and mixed-race hostility, among other baroque charges that have been aired.

Medsger just sticks to the facts, and they are alarming enough. Though obviously sympathetic to the religious anti-war resisters, her style is no way polemical.

As a freelancer, Medsger covered the Camden 28 trial in 1973 and she provides a fascinating account of that important, but underreported, trial. It came a year after the Harrisburg trial, and the national media had little appetite for more blanket coverage of Catholic radicals. (The Burglary pairs well with a recent documentary, "Hit & Stay: A History of Faith and Resistance," that also captures these events.)

Medsger's last chapter is called "Questions," and though she answers most all of them, some remain unanswerable. "Why were the Media burglars never caught?" is one. The FBI, Medsger points out, was locked in a quandary. It wanted to squelch as much publicity about the Media burglary as it could, since the burglary shone a damning light on the bureau's many illegalities. It was Medsger's original article in 1971 at The Washington Post that led to numerous exposés. But even at the Post, the Media burglary was drowned out by the tumultuous Watergate days and the resignation of President Richard Nixon in 1974.

Capturing the burglars would only do what the FBI wished wouldn't happen: bringing, by means of a trial, more attention to its illegal practices. More likely, though, their freedom was the result of the FBI's simple incompetence, much on display then as now -- Hoover's true legacy at the FBI. As Medsger writes:

Just as Hoover's secret FBI's emphasis on conducting political surveillance and dirty tricks -- along with his emphasis on solving easy crimes, stolen cars and bank robberies, while neglecting the crimes that damaged society most, organized crime and government corruption -- distorted the mission and competence of the bureau while he was director, the difficulty of accessing and analyzing the enormous data collections of Top Secret America has threatened bureau competence since 9/11. When the bureau does not know what dots it has, it cannot connect dots.

Medsger's powerful and illuminating book is especially poignant and pertinent now, since the Oak Ridge Three -- remnants of what's left of the Catholic protest community -- recently have been sentenced to prison: three years for the octogenarian nun and five for her two aged confederates. Perhaps if our "anti-war" president read The Burglary, he would be compelled to take out his pardon pen.

[William O'Rourke is professor of English at the University of Notre Dame and the author of, among other books, The Harrisburg 7 and the New Catholic Left. A 40th anniversary edition, with a new afterword, appeared in 2012.]