The casket of Cuban Cardinal Jaime Ortega, is seen during his funeral Mass at the cathedral in Havana July 28, 2019. (CNS photo/Fernando Medina, Reuters)

Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago promulgated revised guidelines for funerals on All Souls' Day. The document doesn't exactly break new ground in its recommendations, which range from when and where a vigil or wake is to be conducted to the church's approach to cremation and treatment of cremains, but it does put heavy stipulations on where, when and how a eulogy can be given.

"Eulogies, stories, and favorite songs are most appropriately shared during this time of visitation at the Evening Vigil," the guidelines, "When the Time Comes: A Resource Guide for when Catholics enter Eternal Life," state. "The pastor of the parish may allow a reflection by one individual. This is to take place between the Post-Communion prayer and the end of Mass. The personal reflections should be limited to 3 minutes and are to be presented in writing to the pastoral minister assisting the family in advance of the service."

This rule draws a firm line through a sensitive pastoral context, in which grieving families are processing their loss and navigating how to say goodbye. The Chicago guidelines track with those promulgated in other U.S. dioceses, some of which exercise even stricter measures for eulogies, relegating them exclusively to funeral vigils. The guidelines in the neighboring Diocese of Rockford, Ill., issued in 2002, are nearly identical in their approach to eulogies.

Advertisement

"There's not a radical departure of what we said previously, but it is certainly more direct," said Fr. Lou Tylka, chair of the Chicago presbyteral council and, for the last five years, pastor of St. Julie Billiart parish in Tinley Park, Illinois. Sparked by a request from a pastor and then taken up by the presbyteral council, Tylka describes the undertaking as an act of pastoral accompaniment and the responsibility to provide the people they serve with something tweaked "to current reality."

Largely against improvisation

This includes families that are far less connected to the Catholic Church or even unchurched and an increasingly consumerist mindset around funerals, driven by convenience and personal touches. Joan Gecik, executive director of The Catholic Cemeteries in the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis, notes that, while her archdiocese hasn't promulgated guidelines of this sort, her experience in funeral liturgies makes her understand why Chicago would take the step.

"It is very hard for pastors or pastoral ministers, in dealing with families, who basically feel that they have the right to whatever they want — which is again a very consumer-driven understanding of what church is about," Gecik said, counting the experiences of people hijacking the liturgy with a 20-minute, improvised eulogy that "thoroughly embarrassed the family" among the horrible results.

Cardinal Blase J. Cupich of Chicago swings a censer over the casket of retired Archbishop Harry J. Flynn of St . Paul and Minneapolis during his funeral Mass Sept. 30, 2019, at the Cathedral of St. Paul. (CNS photo/Dave Hrbacek, Catholic Spirit)

The Chicago guidelines state, "Experience shows that sharing personal remarks at the Funeral Mass can be inopportune for a number of reasons. It can create hard feelings if hurtful things of the past are raised or create discomfort in ill-advised attempts at humor. There are also concerns in view of past experiences that eulogies can overshadow in length and attention the Funeral Mass itself, especially if those offering words turn the Church's rites into a celebration of life that focuses only on the accomplishments of the deceased's past, with scant attention to our faith in the resurrection."

Tylka emphasized that Catholic funerals are also ultimately about looking forward in hope to the resurrection and to joining our loved ones in the life that God has prepared for us. "If we don't center ourselves on our belief in Jesus as the one who is raised from the dead who gives us eternal life, then we lose something."

In accompanying family's through the decision not to go off-the-cuff, Tylka said he has had family members express relief afterward. "I could never have talked about my mom in that moment, like I thought I could have," is one comment he recalled. "To turn around and look at your family and also know that the remains of your loved one are either before you in a casket or in an urn," he noted, "the emotional moment can overcome you." He added that even though his parish averages 110 funerals a year, "there are times when even I get emotional because of a connection to a person."

Healing role of remembering

But grieving families still see the role of the eulogy as important, whether in reduced/restricted form or not, especially in an age when more and more families are less and less Catholic. Melina Birchem of Brainerd, Minnesota, in the Diocese of Duluth (which also has guidelines similar to Chicago's), recalled that her 92-year-old grandmother's funeral Mass, despite its liturgical beauty, was also uncomfortable, save for its liturgy.

"My mom is the youngest of 12, we're all raised Catholic, but only my mom and one of her brothers are still Catholic," she said, and so most of her family didn't connect to the liturgy "or were very uncomfortable with it." But that changed when an aunt spoke after communion.

"It was this reconnecting point — something I could listen to and understand because it was coming from someone who knew my grandma, who drove three hours every weekend to care for her," Birchem said. "My Aunt Sarah brought me back in that eulogy, and it also united my family and gave us a connecting point even if we didn't stand on the same faith grounds —or in the case of a few of my aunts and uncles, really no faith at all."

"If we don't center ourselves on our belief in Jesus as the one who is raised from the dead who gives us eternal life, then we lose something."

—Fr. Lou Tylka

Birchem notes that her aunt honored the resurrection-centric spirit of the funeral Mass, "focused not on funny jokes but by giving us the outline of the woman we lost but the saint we gained." She added that she recognizes that stories, jokes and otherwise memorializing a deceased loved one also have a place in Catholic funeral rites, albeit apart from the Mass.

Gecik in St. Paul and Minneapolis noted that the Order of Christian Funerals outlines three distinct steps — the vigil, the Mass and the burial — but that over the last 10-15 years, most people skip the vigil. She said the one vigil she's attended in the last decade was "a wonderful experience," a "time to share with the family in the context of ritual and song," but also a more relaxed format where the sharing of stories is more appropriate.

Foregoing the vigil, on other hand, creates pressure for the funeral Mass to be everything.

"I've heard from a number of people in my work that some of this is for cost, because if you have a vigil service in a funeral home, there's a cost associated with it," Gecik said. "Many families feel, 'Well, this is enough. … We're only asking people to come out once. People can come out before the Mass to visit with the family very briefly.' I don't think it does justice to allowing people to really visit with the family. But it's kind of the way the culture has gone."

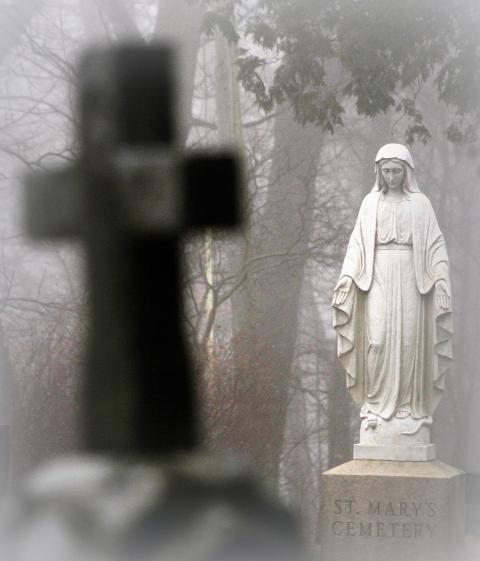

A statue of Mary and a grave marker at St. Mary Catholic Cemetery in Appleton, Wisconsin. (CNS photo/Brad Birkholz)

Gecik noted that Americans "want things done quickly, efficiently. We want it done and gone. And I especially see this around death." And this can be found in less bereavement time being offered by employers and other efforts to make funerals as quick and convenient as possible. "It's something that you check it off your list and you get on with life. That's not at all what we believe."

Consistent support

Other Catholics who shared about their experiences noted the need for grieving loved ones to receive consistency from the church, that is, that guidelines for funerals should be consistent from parish to parish and from family to family. In this regard, the relatively high-profile promulgation of the Chicago guidelines presents an opportunity for unity and deeper understanding. Dominican Sr. Lois Paha, director of pastoral services for the Diocese of Tucson, sees the value in Chicago making a teaching moment out of the guidelines and said she appreciates the archdiocese's inclusion of cremation and other issues.

"People need to remember that the church is present for all of their needs," she said. A holistic approach to the issue of death and dying, she added, is part of the wider fabric of the church's pastoral care, she said, because full and active participation in the life of the church comes "through liturgy and service."

[Don Clemmer is a journalist, communications professional and former staffer of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. He writes from Indiana. Follow him on Twitter: @clemmer_don.]