Palestinians light candles before Christmas morning Mass at St. Catherine's Church, adjacent to the Church of the Nativity, in Bethlehem, West Bank, Dec. 25, 2021. (CNS/Debbie Hill)

In Kelley Nikondeha's new book The First Advent in Palestine, we go on a journey that isn't easy, comfortable or filled with the same nostalgia that many Advent books hold. But this book gives us something more: it takes us on a journey of truth telling, care, justice and hope. It gives us insights on what we can do with the life we’ve been given and a history we have told time and again.

I interviewed Nikondeha for NCR to raise questions about how we can embrace an Advent season that is truly for the life we are living here and now, one for all people and not just those for whom hope comes easily. May we live with courage for what this narrative of liberation requires of us.

NCR: You write of Mary in the book, "And while she was not yet significant, I doubt she was ever known for being meek or mild." What violence is done within the church by characterizing Mary as a meek, gentle girl and not a strong, empowered woman who was fighting (and singing) for justice — and her own healing?

Nikondeha: Many of us have been given a picture of Mary as an icon of purity. That serves the patriarchy quite well: this idea of a pure, submissive young girl. But I don't actually think that's the best way to understand her. Mary was formed from, by and for resistance — in particular, resisting the empire of her day for the sake of liberation.

She was invited into the liberation story of Advent, of Christmas, for the sake of her people. It's easy to say that she was invited to be the mother of Jesus, but even that domesticates what was happening in the text. What's happening is that Mary, coming from a very hard place in the Galilee region, is invited by God to be part of a liberation movement, not JUST to be a mother, which was expected of girls at that time.

This invitation to Mary is extraordinary because she's invited to play a key role in God's liberation movement through motherhood. Motherhood is the vehicle. So we should see Mary more as an icon of resistance, not of the patriarchy. And I hope that would do service to Mary's story, that it would also have the potential to be more generative, especially for women in the church. Maybe it would make her more relatable to know she’s come from a hard place and suffered hard things and still stepped into this work that God invited her into. She's such a compelling example of what's possible.

Let's get deeper into the power of art, because it's an important element in your book and in the stories you share about Palestine. How has art been used as a tool of resistance and resilience?

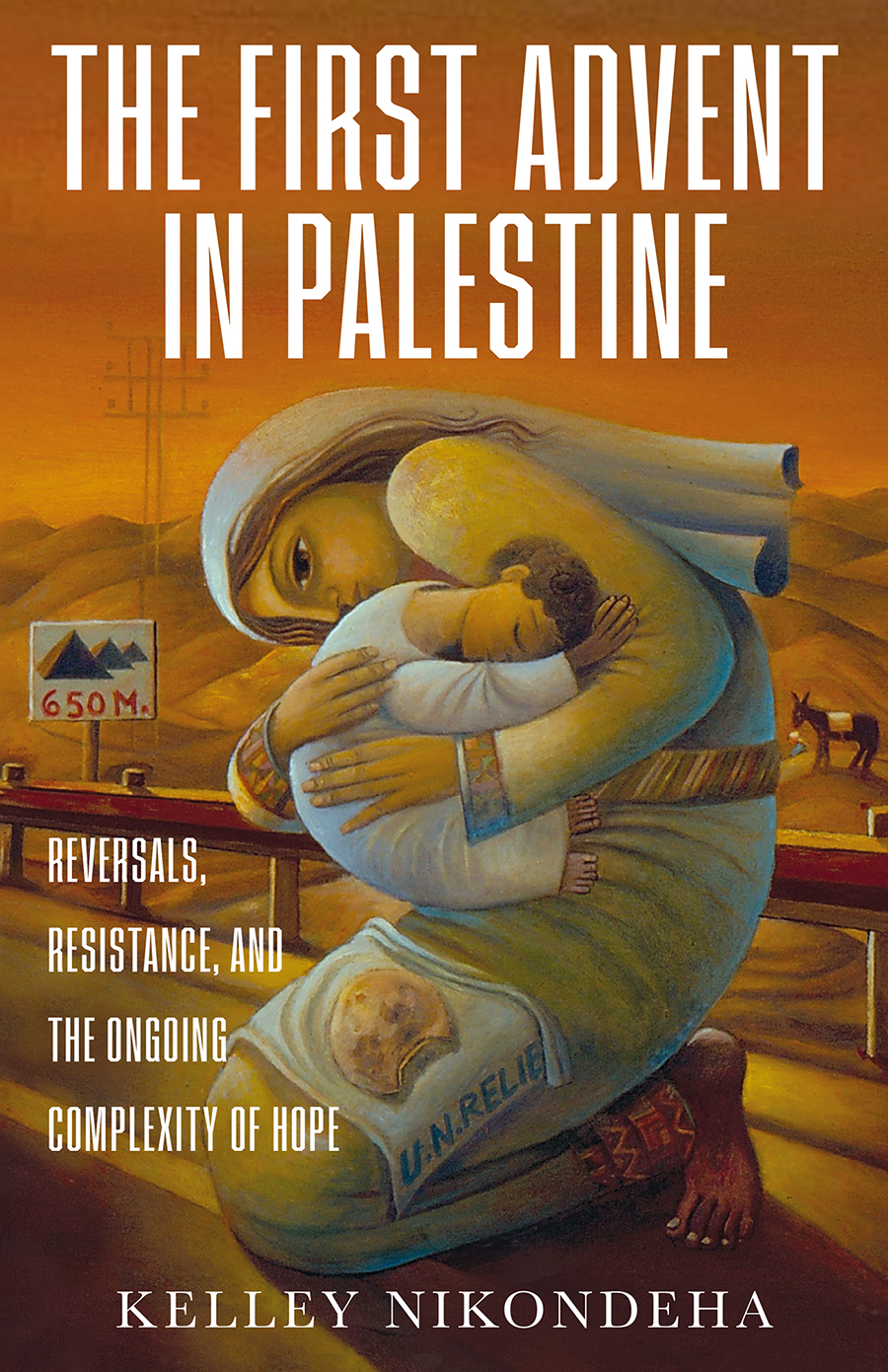

There is an art gallery at a hotel in Bethlehem which has the "with the worst view in the world," according to the artist Banksy, because it is a direct view of occupation. In the lobby there's a lot of Banksy's work, which is, of course, resistance art. But upstairs is a gallery with only Palestinian artists showing their work; the famous Palestinian artist Sliman Mansour has pieces there. I remember standing in front of one of his pieces, immovable, because the story he was telling was so captivating.

I now know that Mansour is in his 70s and he's known as the Palestinian artist of resistance. He's kind of a hero of his people. He didn't set out to be a political figure, just an artist. But when your people are oppressed, you can't help but reflect that in your artwork.

While there, I was thinking that in a sense that he is a star in Bethlehem, because he shines a light on the reality of what's happening in Palestine in his artwork. But he's also lighting a way forward, the hope of what could be resurrected or more fully embraced on the other side of occupation.

I find that artists like that in Palestine (and around the world) provide the necessary illumination and function as stars: shining a light on the truth and shining a light forward. I don't think you can pull those two things apart, and that’s what I love about the work of so many Palestinian artists. They show you reality, creating space for you to feel it, and they are whetting the appetite for what could be. That's the job of artists. That's how they change the world.

Advertisement

You mention the work of activist Sami Awad and that he works for peace by "connecting people." Living in such a divided and tumultuous society today, it feels like peace is totally lost. How do we hold on to the power of community and connecting people in the midst of this?

When I think about my time with Sami in Bethlehem, I remember that he was expressing a lot of hopelessness in conversations about justice and reconciliation, because he couldn’t see a way forward in any immediate sense. But he continued to create space for people to come together and share their stories and connect. He somehow knew that those connections would eventually bear fruit.

I'm reminded of how Jesus answered the question are you the one? He'd answer them by saying come and see. The come and see is an invitation to connect in a very embodied way. The power of connection is also an invitation to pilgrimage, not for the sake of personal piety or individualistic spirituality, but to journey into someone else's reality.

When I traveled to Palestine and had tea with Sami, it was sacred. Being in another's space and place disarms us, allowing us to dislodge some of our prejudices and maybe even help us get rid of those calcified ways of thinking that we showed up with. We can take a pilgrimage across the ocean, but we can also take one across the street, entering into the world of our neighbors.

Pilgrimage is a metaphor for walking into the world of another person. Peace activists like Sami understand this, and we can learn a lot from them by taking the time to ask what our own pilgrimages should look like.

So much of this book and your work touches on cycles and systems of hope and hopelessness. Oppression cycles throughout history, changing its face but still holding so much power over marginalized peoples, and this can often feel hopeless. When we talk about hope, what's the difference between shallow hope and a deep, subversive hope?

I think when we look up to the stars without surveying the reality on the ground first, we’re going to be engaging in a shallow kind of hope, where we just want to launch straight into what is shiny and good and promising without wrestling with the actual hardship that is being experienced on the ground. When we look at the realities around us and engage them as such, a hard-born hope can emerge. It's deeply connected to the loss and the lament of the place as well.

I've been recently reading a book called Embracing Hopelessness by Miguel A. De La Torre. In the book, he writes about how hope can be used to pacify or numb people so that they are not fully engaged with the world around them, just waiting to die and go to heaven. So hope can function to keep oppressed people complacent and De La Torre is advocating for an embrace of hopelessness, so that when we allow ourselves to see how bad it is to live with injustice and to name the territory accurately, it makes us dissatisfied enough to be a catalyst.

Then we will say, "There has to be another way," which leads to organizing, moving together toward what I would call hard-born hope that comes out of that real, lived experience. Then we can engage the injustice and determine together that we are going to change the lay of the land. We must allow the hopelessness to energize newness through the Spirit. But you don't get to hope without reckoning with the loss and engaging collective lament.

These are the things that good artists invite us into. It's the work of activists around the world. It's what the Biblical text offers us: to feel bereft and to trust that we will be energized to create something new.