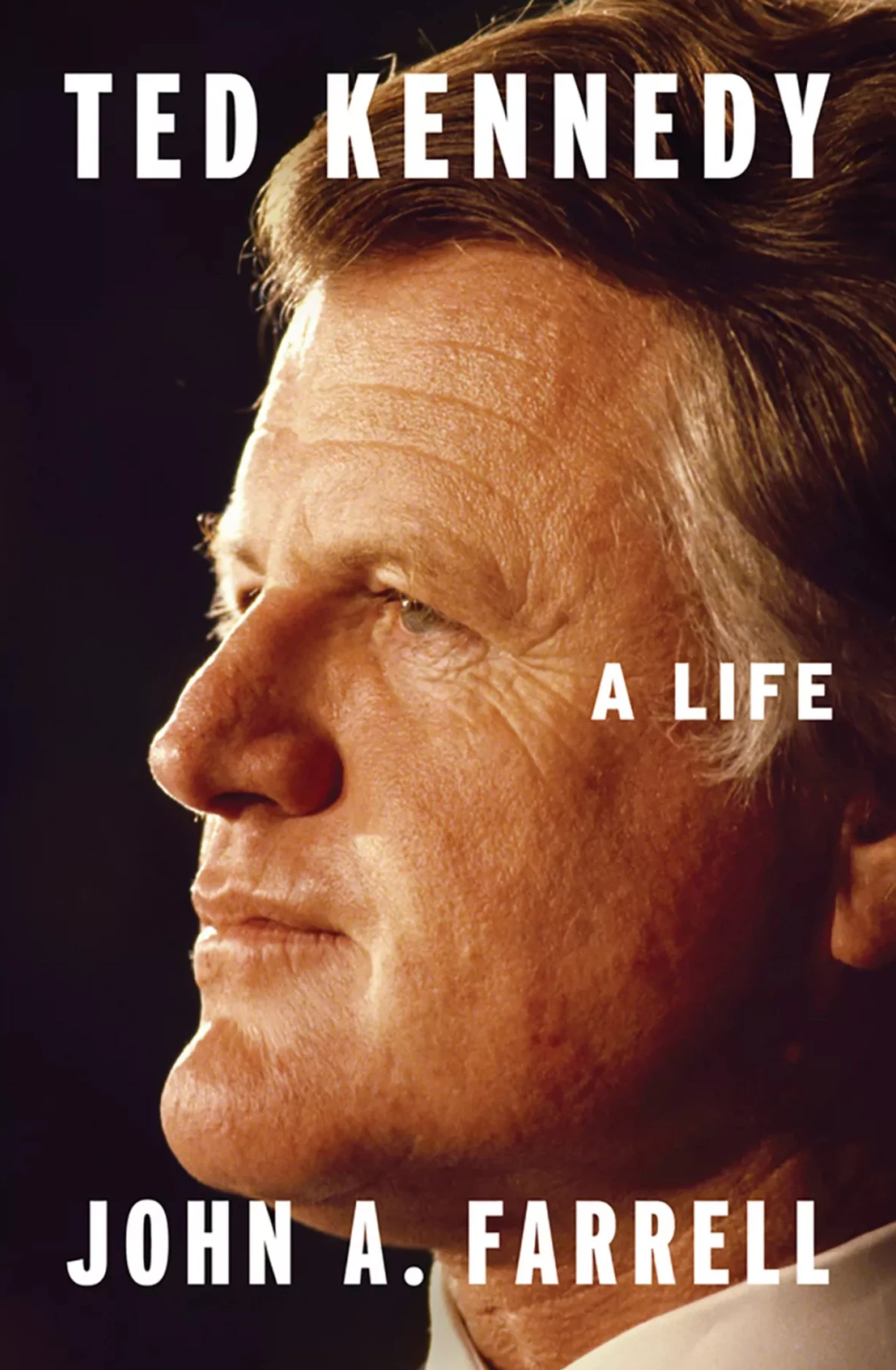

Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Massachusetts, attends an organizational meeting of the Senate Judiciary Committee as its chairman in Washington, D.C., Jan. 24, 1979. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division/U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection/Thomas J. O'Halloran)

Biographical portraits published during the lifetime of the youngest brother in America's most famous Catholic family tended toward partisan poles. Depending on the author, Ted Kennedy was either a sentimentalized liberal lion who fought in vain to fulfill the dreams of his brothers or a buffoonish blowhard who split his time between criminality and crafting ill-conceived public policies.

In Ted Kennedy: A Life, author John Farrell goes to neither extreme. Instead, Farrell strikes a deliberate balance between the man and his work while staying largely out of the partisan fray.

Much of this essential new biography of Kennedy focuses on two matters, both arising from Farrell's access to unprecedented resources — namely, portions of the late senator's personal diary, and selections from the diary of historian (and Kennedy ally) Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

The first such revelation is particularly topical. According to Kennedy's diary, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito, who wrote the 2022 decision overturning Roe v. Wade, assured the senator in private that he regarded the 1973 decision as precedent. This assurance came while senators weighed Alito's worthiness for the high court in 2005. Alito stated that he planned to adhere to Roe, but Kennedy doubted that — with apparent good reason.

There is no place where Ted Kennedy's perseverance through personal tragedy is more evident than in the tally of his legislative accomplishments.

The other major disclosure is perennial to any discussion of the youngest of Joseph and Rose's nine children. Revelations in Schlesinger's diary seem to confirm what many observers have long suspected about Ted Kennedy's behavior in the hours after the 1969 Chappaquiddick car crash that killed Mary Jo Kopechne. Apparently, Ted told his sister Jean Kennedy Smith that in the panicked hours after the crash he tried in vain to find a way to cover it up.

While these revelations are significant, they far from tell the whole story of Farrell's thorough and thoughtful account of the Senator's life.

Farrell's previous political biographies include esteemed takes on Tip O'Neill and Richard Nixon. The author's bona fides as a biographer are further established by this account of Edward Kennedy. Farrell has the distance and the sources to render the man with unprecedented fullness.

He takes particular care to present the blow-by-blow of Kennedy's admirable curriculum vitae. Edward Moore Kennedy was a public figure for longer than his brothers Joe, John and Robert were alive. His accomplishments as a policymaker are also significantly more substantial than those of his brother the president and his brother who nearly became president.

Virtually every piece of liberal legislation signed into law between the mid-1960s and Ted Kennedy's death in 2009 bore his strong imprint. This legacy includes civil rights, voting rights, fair housing legislation, immigration reform, the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Affordable Care Act, which was signed into law seven months after his death.

Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Massachusetts, addresses a rally for reform of immigration law April 10, 2006, in front of the U.S. Capitol in Washington. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

Kennedy presented as the standard bearer of a past Age of Enlightenment but worked the corridors of power with a pragmatism that made him one of the most effective legislators in the history of representative government.

There is no place where Kennedy's perseverance through personal tragedy (including two of his three children battling cancer) is more evident than in the tally of his legislative accomplishments, laid bare in Farrell's account. Kennedy could negotiate and make deals inside and out of his caucus as well as anyone, apart from family nemesis Lyndon Baines Johnson. Kennedy's inherited gift of gab and abundance of charm didn't hurt this cause.

Farrell gives the impression that Kennedy's ill-fated plunge into the 1980 Democratic primaries proved a boon to his later legislative efforts by unbinding him from other people's aspirations. It also corresponded with the end of his long-troubled first marriage, a subject Farrell addresses in a clear-eyed but never gratuitous fashion.

On personal matters, Farrell proves plenty willing to delve into Kennedy's demerits. He plays all the greatest hits of his subject's personal flaws: his expulsion from Harvard for cheating, his boozing and carousing and his often-atrocious personal judgment. Farrell emphasizes the degree to which Kennedy's well-publicized mistakes prevented him at times from advocating effectively for the policies he championed.

This not only goes for the Chappaquiddick affair hamstringing his presidential aspirations; Farrell also delves into Kennedy's silence during the 1991 Clarence Thomas hearings.

Advertisement

Earlier that year, the senator had spent an evening at a Palm Beach, Florida, bar with his son Patrick and nephew William Kennedy Smith. The evening ended with his nephew arrested for sexual assault, a charge for which he was later acquitted.

With Smith's trial looming, Kennedy contributed little regarding Anita Hill's accusations of sexual harassment against Thomas. Despite his presence, Kennedy played only a minor role in the contentious Supreme Court hearings, which helped reshape the discourse surrounding personal conduct in the workplace.

Catholic readers will take particular interest in Farrell's thorough discussion of Kennedy's role in immigration reform. The present-day vibrancy of the Catholic Church in the Southwestern United States and the continuity of the church in many American cities, including Kennedy's hometown of Boston, are a product of the immigration policies the then-junior senator helped bring about in the 1960s.

His brother John's administration failed in its efforts to unmoor the nation's immigration policy from a quota system put in place during the 1920s. It took the efforts of the youngest Kennedy to shepherd a bill that radically remade the nation's immigration system. The new law ended the old quotas based on the 1890 Census, encouraged family reunifications and created a framework for refugee resettlement.

In subsequent decades, millions of Catholics from Latin America, Africa and Asia made use of these new pathways into the United States. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act made the Catholic Church in America again a living, breathing immigrant church. In the long run, this may be the late senator's most significant legacy.