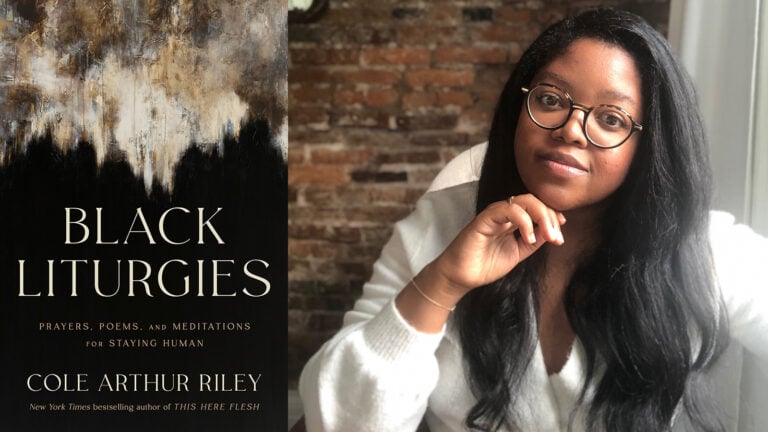

'Black Liturgies: Prayers, Poems, and Meditations for Staying Human' and author Cole Arthur Riley (RNS)

The Sunday after the murder of George Floyd, the liturgies of Thomas Cranmer weren’t cutting it.

In her latest book, Cole Arthur Riley describes logging in to an online Episcopal church service that day, grapes and hot Cheetos close at hand.

"And I waited, knowing what I’ve always known: that there are days when it is particularly difficult to pray words written by a white man," she writes.

The Book of Common Prayer, penned in the 16th century by Cranmer and used in many Anglican traditions, was not crafted with Black people in mind, Arthur Riley said.

"I know what was happening to my ancestors," Arthur Riley told RNS about the era in which the collection of liturgies was written. So, Arthur Riley began writing her own liturgies, centering Black emotions, experiences, memories and bodies in every prayer, mantra and poem. As she shared the liturgies on social media, they began to resonate with thousands aching for a sacred space that centered Black healing and rage. The Black Liturgies account on Instagram has since gained more than 380,000 followers.

She describes her latest book, Black Liturgies: Prayers, Poems, and Meditations for Staying Human, as a "physical artifact" of that digital project. Including letters, poems and hundreds of new prayers on everything from Black Twitter to healing from church abuse, Arthur Riley’s book is never prescriptive and is held together by the author’s vision of spiritual liberation. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

RNS: What are breath prayers, and why include them in your book?

Arthur Riley: The way I practice it, it’s connecting simple phrases to the breath. In this season of life for me, the breath as prayer, the body as prayer, is increasingly important. I know what it is to ignore and sacrifice my body in the name of the sacred. I was taught to sacrifice my body for God far more than I was taught to breathe, rest, lie down by still waters, eat and drink. As part of writing an honest spiritual text, I needed to include the body. Just as much as language can be a portal to connecting with God, so can the body and breath itself.

Some of your prayers are very specific — for the kitchen, for those who doom scroll — while others are more general. How do you balance specificity and expansiveness in your liturgies?

I am very interested in particularity. In my last book, This Here Flesh, there’s a lot of minor stories as opposed to the grand narratives of my family’s life. Sometimes it’s specificity that people connect with because it tends to be more honest. But also there are things that connect us and transcend. So I included some of those as well. But I didn’t really think about that distinction. It’s maybe just a reflection of our lives. They’re comprised of moments that at times feel like they stretch to other people and at times feel so specific, but I think allowing that to be the case is so important. Something like the Book of Common Prayer, which I love, is still very general. And there’s something interesting about having a prayer book that has prayers in it that aren’t for everyone. It trains us in a particular way of being or existing with God. You can allow that decentering and recentering dance to happen.

Your grandmother’s story was strongly interwoven throughout your last book. How does your grandmother continue to live on in this one?

In the artistry section, I talk about her explicitly, but I think it applies to the whole book, this sense of my grandma being very unapologetic about being an artist, a poet. She was existing in a time where no one was giving her any real affirmation. She had one poem published in a small anthology, but apart from that, she will not be remembered as a writer by many people. Still, she had this fidelity to the pen. Every day she was writing. Whatever was in her that allowed her to continue to pick up the pen with so little affirmation from the world around her, I think I needed to at least approach a fragment of that to write this book.

In the section on doubt, you write that religious certainty can be a form of white supremacy. How does doubt inform these liturgies?

So many of us know what it means to belong to spaces that demand you believe a certain thing to belong. I find that path to belonging so sinister. You end up with people claiming they believe all kinds of things if it means they can sit at the table with you. I find that frightening. I think about all the people who don’t really believe in the limited things they say they believe. I feel a lot of compassion for people like that. I also feel compassion toward people with great doubt who are forced to hide it. I think white supremacy pervades in the Christian demand for certainty above all else. I think something can have meaning without needing to conquer other things.

So how does it show up in this book? At the end of the day, I have to contend with the fact that I wrote a prayer book to a God that I’m not convinced exists. I have more doubt than certainty. But to me, there’s meaning and value in the attempt to connect with the divine. I hope there’s some kind of mystical force at the other side of the conversation. But if not, there’s still meaning in how it’s bringing me closer to myself, how it’s bringing me closer to the face of my neighbor.

Did crafting these liturgies shape or stretch your spirituality in any meaningful ways?

I realized how little I personally think about Christ as I’m praying. Maybe I’ve felt some degree of guilt or distance from God because of that. I think this book helped because I was trying to be intentional about not making the liturgies exclusively Christian. That permission to approach the divine in the way that feels right depending on where I am that day was healthy and healing for me.

How do you imagine readers, particularly the Black communities you’ve intentionally centered, engaging with these liturgies?

I had different images that would resurface as I was writing. I had this image of a group of women sitting on couches, talking, eating and maybe pulling the book up for a second and putting it down. I also can imagine it being used in more structured spiritual spaces. A few churches reached out and said that they are using it, which is just wild. I also think of untraditional spiritual spaces. I could picture people in the park or pulling it up at a family reunion. I think the beauty in it for me is that it doesn’t need to all be encountered at once, or only to be encountered in one way.

Advertisement