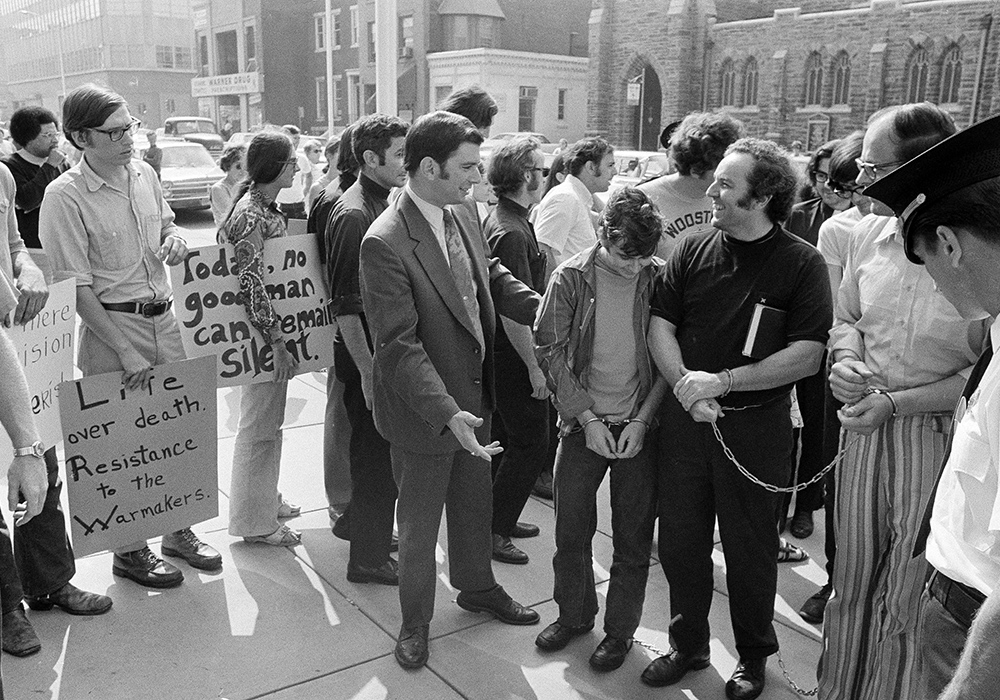

Supporters of persons arrested a week earlier in an attempted raid on a Selective Service office greet those arrested at a court hearing in Camden, New Jersey, on Aug. 30, 1971. Those arrested were brought from a New Jersey jail in handcuffs. Among them is John Grady, right, handcuffed, wearing black. They became known as the "Camden 28." (AP photo/Bill Ingraham)

"Is There Anything Left of the Catholic Left?"

I knew I was going to enjoy Spiritual Criminals: How the Camden 28 Put the Vietnam War on Trial, Michelle Nickerson's rollicking account of Catholics raiding a draft board office in Camden, New Jersey, when I spied that question in its table of contents.

Nickerson's book begins with a crash course in "the Catholic Left" as it existed in the 1960s and '70s. Catholics were enjoying a new assimilation into and acceptance by wider American society in the aftermath of World War II, yet an unpopular but vocal contingent rejected war and the warmongering that fueled the engines of U.S. consumerism. After 1964, when President Lyndon Johnson escalated the deployment of U.S. troops in Vietnam, the Catholic peace movement gained a wider following.

With the stage set, Nickerson turns her attention to Camden, New Jersey, where St. Vincent Pallotti Church, in the suburbs of Camden, offered a "folk Mass" that had become a hub for families and young people. After Mass, parishioners often discussed their anti-war views over meals and carpooled to peace protests.

In the fall of 1970, some members of the folk Mass crowd invited a trifecta to help them plan a draft board raid: John Grady, a married man with five children, and Kathleen "Cookie" Ridolfi and Anita Ricci, both in their early 20s and friends since grade school. Grady was twice the age of both Ridolfi and Ricci — and carrying on simultaneous affairs with both. The three "traveling companions" had planned other anti-war actions along the Eastern Seaboard. This "problematic love triangle," as Nickerson calls them, became the foundation for the Camden action.

In one swift chapter, Grady, Ridolfi and Ricci gather the 25 others, "Ocean's Eleven"- style, and plan their raid of the draft board office in Camden's federal building for the early morning hours of Sunday, Aug. 22, 1971. After eight trespassers vandalized the draft board office for several hours, they and their lookouts were intercepted by FBI agents, who had been tipped off to the raid but let them proceed in order to catch the activists red-handed.

During their three-month-long trial, the activists (who became known as the "Camden 28") mounted a thorough moral defense of their actions and called on stellar expert witnesses in Dan Berrigan, the Jesuit priest and a perpetrator of the burning of draft cards in Catonsville, Maryland in 1968, and Howard Zinn, the socialist historian. Their arguments paid off: the dramatic trial concluded with an unexpected finale.

Nickerson's question — Is there anything left of the Catholic left? — remains salient.

A book like Spiritual Criminals has the potential to offer a significant contribution to U.S. Catholics' understanding of our history and provide inspiration for political activism today. Nickerson's question – Is there anything left of the Catholic left? – remains salient. And the endings to the Camden 28's stories can help provide an answer.

Although many in the group went on to try to live ethically in an economy built on exploitation and destruction, few of the activists continued to live in a radical way, challenging the status quo or forging bold new paths of Gospel living, according to Nickerson.

After their triumphant trial, the stories of the Camden 28 end with the whimper of assimilation rather than the roar of transformation. I wondered if this was, in part, due to the fact that the tactics of the group resembled too closely the tactics of the government they were protesting — a resemblance that became a crucial plot point in their trial.

"The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house," feminist author Audre Lorde declared in a 1979 address. "They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change."

Throughout her story of the Catholic left, Nickerson notes the many sexual liaisons of older men in the anti-war movement (many of them either married or priests) with younger, idealistic women. Nickerson maintains a scholarly and historiographic remove from these incidents, but I would have welcomed more analysis of these patriarchal gender dynamics and how the injustice baked into them may have undercut the goals of the Catholic left. Too many of our houses are built with the master's tools.

Advertisement

Patriarchy claims that to own something — or someone — gives the owner the right to abuse, misuse or destroy it. Reading the Camden 28's story, I wondered if a model of civil resistance that focuses on destruction rather than regeneration has sufficiently freed itself from the logic of patriarchy.

In a less patriarchal paradigm, ownership and responsibility are not defined by domination or coercion — or the right to destroy — but by care. Justice consists of tending to, caring for and handing down. One thread of the Catholic left that Nickerson highlights reflects this alternative logic, and could offer a less patriarchal paradigm for Catholic action: liturgy.

During an Ash Wednesday liturgy several months after the raid, one of the Camden 28 — the Irish priest, Michael Doyle — inscribed ashes from burnt copies of the Pentagon Papers, rather than palms, on the foreheads of his congregation. On the same day, Nickerson notes that Dorothy Day was in attendance at a similar liturgy where draft cards were burned, across the river in Philadelphia. Despite Day's concerns about many war protestors' destructive tactics, Day found the liturgy moving and beautiful.

The liturgical movement, which was a powerful influence on Day herself, held that the central act of Christian worship contained a call to reconstruct the social order in the image of the God of justice and mercy: a call to welcome the stranger as Christ — to live in solidarity with one another as Christ's mystical body rather than divided by race, nation or gender; in short, a call to live the Eucharist as though it were true.

I wonder how differently the Camden 28 stories might have ended had their parish community been a hub of not simply resistance to evil but of creating this new, tender society of justice and care that the liturgy calls forth. What if our parishes were places where we could live in interdependence with one another and the earth in a way that precluded a need to depend upon the American war machine and the economy built upon it?

"Without community, there is no liberation," wrote Audre Lorde, "only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between an individual and her oppression." Perhaps, if Catholic communities could become these schools of liberation, there might be more left of the Catholic left.