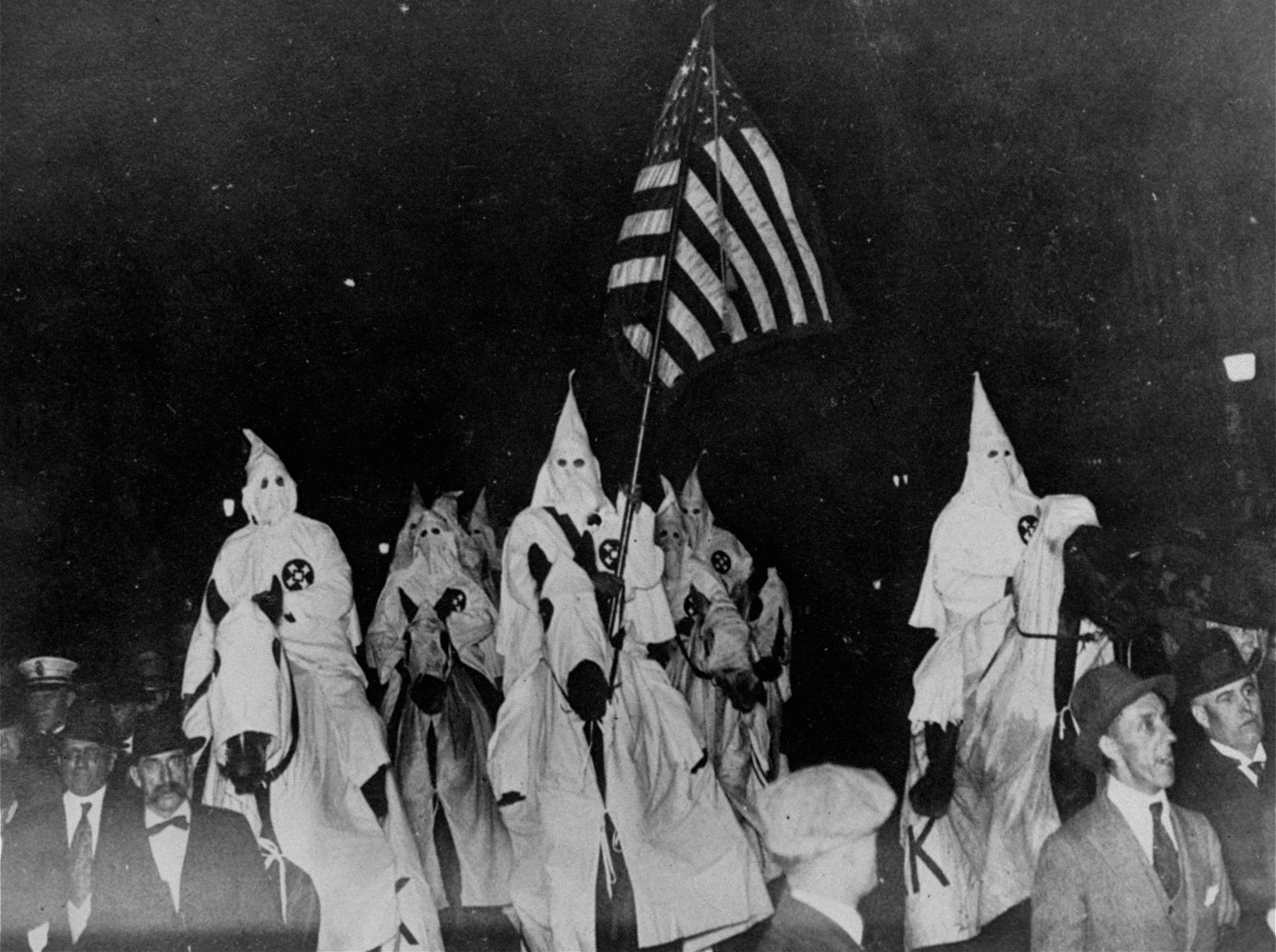

The Ku Klux Klan parades through the streets of Tulsa, Oklahoma, Sept. 21, 1923. (AP)

As the right-wing movements of intolerance gain greater and greater hold over the levers of American political and judicial power today, historians have begun to examine their roots in earlier periods of American history. Timothy Egan's A Fever in the Heartland draws powerful and uncomfortable parallels between the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and the rise of the MAGA movement in the past decade.

Linda Gordon's recent history of the Klan addressed this same period and argued persuasively that the 1920s Klan was no fringe extremist movement, but rather a mainstream American cultural, economic and political force that swept the nation. Timothy Egan, a prolific author of at least 10 nonfiction books, New York Times columnist and winner of the National Book Award for his history of the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression, takes a slightly different approach. He focuses intently on a particular Klan organizer with unsettling parallels to some of today's right-wing leaders.

Religious bigotry animated the 1920s Klan powerfully. That bigotry had deep roots and widespread reach among America's white Protestant population, a significant portion of whom embraced the violent intolerance for Catholics, Jews and Blacks that the Klan inflamed. Egan is less interested in conveying the breadth of this activity than he is in examining the moral hypocrisy that the Klan leaders practiced as they led what Klan members saw as a movement to restore moral integrity to American culture. He directs his focus tightly around the rise, rule and eventual downfall of the Klan's most dynamic and powerful leader, D.C. Stephenson.

D.C. Stephenson, grand wizard of the Klu Klux Klan in Indiana and other northern states during the height of Klan power in the 1920s, is seen in this Dec. 12, 1922, Indianapolis Star photo. (Wikimedia Commons/Public domain/Indianapolis Star)

Madge Oberholtzer, seen in this circa 1925 photo, died after KKK leader D.C. Stephenson raped her and she took poison. Her deathbed testimony led to his downfall. (Wikimedia Commons/Public domain)

Though many Americans likely associate the Klan with the American south, where it first began in the 19th century and where it held powerful sway in the 1920s, Egan points out that the northern Klan did the most damage. He notes that the state with the highest percentage of Klan members and the state in which the Klan exercised the most complete control over state and local governments was actually Indiana. Hoosiers happily welcomed — even championed — efforts to constrain Catholics and Jews, to limit their economic activities and their participation in civil life and to target Black people even more intently and violently.

But if Indianans, Ohioans, Pennsylvanians and Michiganders were ripe for exploitation, it took D.C. Stephenson's skillful manipulation to turn that anxiety and hate into Klan memberships. He sold the hooded order masterfully through such tactics as large outdoor rallies, parades and visits to Protestant churches. And, of course, cross burnings.

Egan twins his telling of Stephenson's rise to prominence with the parallel story of his personal venality and moral failings. We learn that Stephenson was a charismatic salesman whose oratorical and organizational skills ballooned the Klan's membership throughout the northern states. He sold a Klan that focused intently on cleansing American society of moral ills and those whom he blamed for fostering those ills: Catholics, Jews and Blacks. He exhorted Klan recruits and members to prohibit alcohol's sale and consumption and to police their neighbors' sexual activities. The Klan he led corrupted local and state law enforcement so that police and prosecutors bullied dissenters and targeted critics. Judges colluded to advance Klan interests. Stephenson thoroughly controlled the Republican Party in Indiana and other states.

[Stephenson's] followers readily overlooked his many moral flaws and hypocrisies to follow him down the path to what they saw as the restoration of a golden era of Christian America.

Protestant ministers joined the Klan enthusiastically and endorsed from their pulpits the messages the Klan wanted people to hear. The Klan would often show up at a church in mid-service, march up the aisle with a sack of money to donate to the congregation and retreat from the church, all in hooded anonymity.

Stephenson himself embodied many of the dangers that he railed against. He married, abused and then abandoned two wives. All the while that Stephenson championed a return to moral greatness, he held alcohol-fueled parties at his mansion and assaulted women to whom he felt sexually attracted.

As he rose in power in the northern Klan he targeted a number of young women. He often promised marriage as he forced himself on them, in the back of his cars or in various apartments and hotels. He sometimes got caught, literally with his pants down and sometimes by police, but always bluffed or bullied his way out of the situation. Many of the police had joined the Klan and were receptive to his explanations or succumbed to his threats. He intimidated his female victims against filing charges or going public. Nobody would believe them, he warned.

Republican leaders feared criticizing the Klan in public and refused to denounce their extralegal activities. What did the excesses matter in service to such a righteous cause?

But then it all came crashing down. Some critics had begun to weaken the Klan a bit, through such tactics as publishing local Klan membership lists and railing against their extralegal bullying. A group of students at Notre Dame in South Bend actually fought back against a group of Klansmen who had gathered to intimidate the Catholic students. (Their physical resistance may even have been the origin of the Fighting Irish nickname.) But the real blow came from a young woman whom Stephenson had ravaged.

Madge Oberholtzer lived with her parents just down the street from Stephenson's mansion. She graduated from Butler College and exemplified the 1920s "new woman" in many ways. She did not necessarily support the Klan's aims, but she worried that Republican budget cuts imperiled her state librarian job and that only Stephenson might save it. She knew well that he controlled the state legislature and the governor.

Riot police stand between Ku Klux Klan members and counterprotesters as they arrive in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 to rally against city proposals to remove or make changes to the city's Confederate monuments. The rally by far-right demonstrators led to the death of a counter-protester. (CNS/Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

The price Oberholtzer had to pay was to go on a number of dinner dates with Stephenson and then, at his insistence, come to his house late one night. Stephenson professed his love for Oberholtzer and forced her to accompany him and two bodyguards on a train headed for Chicago. When she resisted, he raped her on the train. Stephenson also beat her and bit her body in multiple places. In the midst of this multiple-day ordeal, she managed to consume poison.

She suffered tremendous pain, feared that Stephenson would escape responsibility and sought to end her life. Stephenson eventually brought her home, denied any knowledge of her struggles and accused her angry father of trying to extort thousands of dollars from him with a "fictional" story of rape. Stephenson explained to his supporters that his political enemies invented the charges to undermine his important work of restoring America to its greatness.

But Madge Oberholtzer prevailed.

A brave prosecutor sought to convict Stephenson even as Klansmen threatened his life and his family. A local judge allowed the prosecutor to use Oberholtzer's deathbed testimony against Stephenson and an Indiana jury found him guilty of murder.

Advertisement

Stephenson's salacious and malicious behavior helped to undermine the Klan in Indiana and other states. It lost its popular fervor and its grip on the Republican Party. But not before it spearheaded through the U.S. Congress legislation that closed off immigration from largely Catholic and Jewish areas in eastern and southern Europe, established a national prohibition on the sale of alcohol and enacted numerous state and local laws that restricted Catholic, Jewish and Black residents from living freely in those locales.

Readers will likely see in the book's many additional details that I have not conveyed here even more parallels to developments today. Egan conveys deftly the dramatic narrative of D.C. Stephenson's rise and fall and the power he had to captivate many Americans who feared their decline from cultural and political dominance. White Protestant fears did not inevitably turn to hateful attacks on religious and racial minorities; that outcome depended a good deal on Stephenson's masterful manipulation.

But Stephenson did not have to work very hard. His followers readily overlooked his many moral flaws and hypocrisies to follow him down the path to what they saw as the restoration of a golden era of Christian America. Those views did not evaporate with Stephenson's fall from grace. As Egan suggests, they have once more percolated to the surface among those convinced to make America great again.