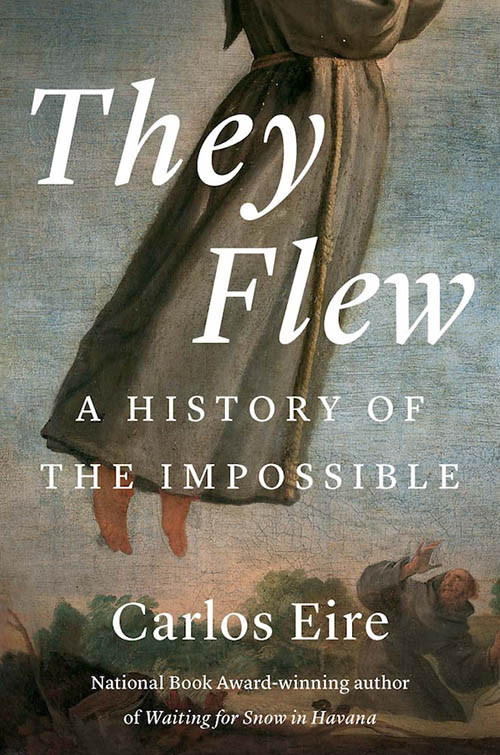

St. Joseph of Cupertino is depicted levitating in an 18th-century engraving by G.A. Lorenzini. (Wellcome Collection)

Imagine being so enraptured by God that you begin to float. For most of us, this could take place only in our dreams. But for a select few, those imaginings are a reality so concrete and yet so wondrous that we are sometimes without words to describe them.

Carlos Eire, the Riggs Professor of Catholic Studies at Yale, is a historian who nonetheless wants to search for words that reflect, or at least give context for, "the impossible."

How, Eire asks, could those who are sane, literate or authoritative in their positions lend credence to the fanciful, even ludicrous notions that people can levitate? How can anyone with an ounce of sense confirm seeing someone defy nature's laws and have the audacity to do so in a court or canonization proceeding? What is it about the power of belief that can infect the masses in such a way as to have them set aside what they think is true and normative in favor of spectacular, mind-bending miracles?

St. Teresa of Ávila in a circa-1903 watercolor by John Singer Sargent (Wikimedia Commons)

I was a student of Eire's while studying at Yale Divinity School. He was fascinated even then by the ideas of the supernatural and mysterious that colored the worldview of Catholic and Protestant Europe, especially in the Reformation era. In They Flew: A History of the Impossible, he brings to bear at least two decades of thinking on the subject.

To get a handle on what he calls "markers of exceptional sanctity," including both levitation and bilocation, and to distinguish them from demonic or magical manifestations, Eire proposes that we reexamine the cases of three principal and famous levitators.

St. Teresa of Ávila, the "reluctant aethrobat," is first in the dock. St. Joseph of Cupertino, whose odd shrieking accompanied his furtive and frequent aerial ecstasies, comes next. The last, Sor María de Ágreda, an "avatar of the impossible," exemplifies the case of a levitator who simultaneously appears in their convent in Spain and the mission territories of New Mexico.

Teresa's mysticism is marked by rapture (arrobamiento) and Eire calls attention to the physicality of the experience. "My body often felt so light that it seemed to weigh nothing at all," she wrote. Though she remained conscious of the ecstasy affecting her, she was in a kind of dissociative state — at once there and not there.

She begged God to refrain from favoring her, not because of her own wants, but because of the wagging tongues of her confessors. In Reformation Spain, flying about could get a girl in trouble.

Advertisement

Church authorities could be harsh skeptics and some had the power to imprison or worse. For Joseph of Cupertino, his levitations were so stirring and unpredictable that his superiors routinely moved him from one friary to another to bring his ecstasies (and popularity) to heel.

The final decision was to ground him in solitary confinement for the last six years of his life. He died in the friary at Osimo, in Italy's Marche, in 1663.

Joseph's levitations might be considered unique were it not for a certain strain within Franciscan life that suggested that religious fervor was connected to abnormal phenomena. The model, of course, was St. Francis of Assisi himself. Thanks to his companions, especially Brothers Leo and Masseo, stories of St. Francis' own levitations made a deep impression on the consciousness of future friars.

Masseo was a witness, but also a participant. Shortly after Francis ordered him to yield, Masseo obediently fell into his arms and was soon set aloft by the power of the saint's own breath.

The impact of the spectacular would repeat in the case of Sor María, who even had the ear of King Philip IV of Spain, but whose life was prone to embellishment. Her popularity was also widespread. Her contemporaries believed she was a saint. The Inquisition had other ideas.

Ostensibly protected by royalty, Sor María spoke of her transvections as if entranced, but gave copious detail on what she saw or felt. The veracity of her accounts of evangelizing the Jumanos of New Mexico left no doubt in the minds of missionaries who had just returned from them. While her writings have been the primary hurdle to her canonization, surely the tales of bilocation also give pause.

It was not the Catholic Reformation that produced so much interest in levitation or reckoned with its phenomena. In an early chapter we get a crash course in the history of the supernatural from much earlier in the church's past, beginning in the second century, with Simon Magnus, a gnostic wonder worker adept in wizardry (see Acts 8:9) whose eagerness for the power over natural laws was his downfall.

To it, we could add that saintly bodies held aloft by some supernatural force in earlier time periods. St. Thomas Aquinas, known for his girth, is a notable instance. While at prayer in a Dominican church in Salerno he was reported to have levitated about 40 inches off the ground, a sign of his "elevation of mind and subjugation of the body."

A 1918 illustration of St. Gerard Majella (Wikimedia Commons)

The canonization records of St. Birgit of Sweden mention several astonished onlookers who saw her take wing. In Raymond of Capua's life of St. Catherine of Siena, we are told a story about Catherine's experience as a young girl enjoying being carried off the ground. "As a fish enters the water and water enters it," he wrote, "so her soul entered into God and God into it."

So many others seem to get in on the act. St. Alphonsus Liguori — sometimes cheekily referred to as "Air-phonso" — would sometimes move skyward while preaching. Not to be outdone, his Redemptorist disciple, Br. Gerard Majella, would also leave terra firma behind while at prayer and bilocate if need be. The Enlightenment had not yet caught up to 18th-century Naples.

Eire's book is liberally illustrated with images of his subjects snared in tree tops, lassoed by fellow religious or kneeling on puffy clouds. They mainly depict a baroque rendition of a person in flight — not just to convey what happened, but also to convince.

Should we, with all our reliance on science and intellectual prowess, throw out at long last silly notions of flying saints? Or by doing so, are we setting the nail in place for a final hammer blow to religion's coffin?

I think back to my grandmother, whose native piety sustained her and often made her appear antique. But I am her progeny and I am conscious that her piety runs through me and can hardly be canceled out. It teaches me to stay open to the impossible, even when shrouded by doubt.