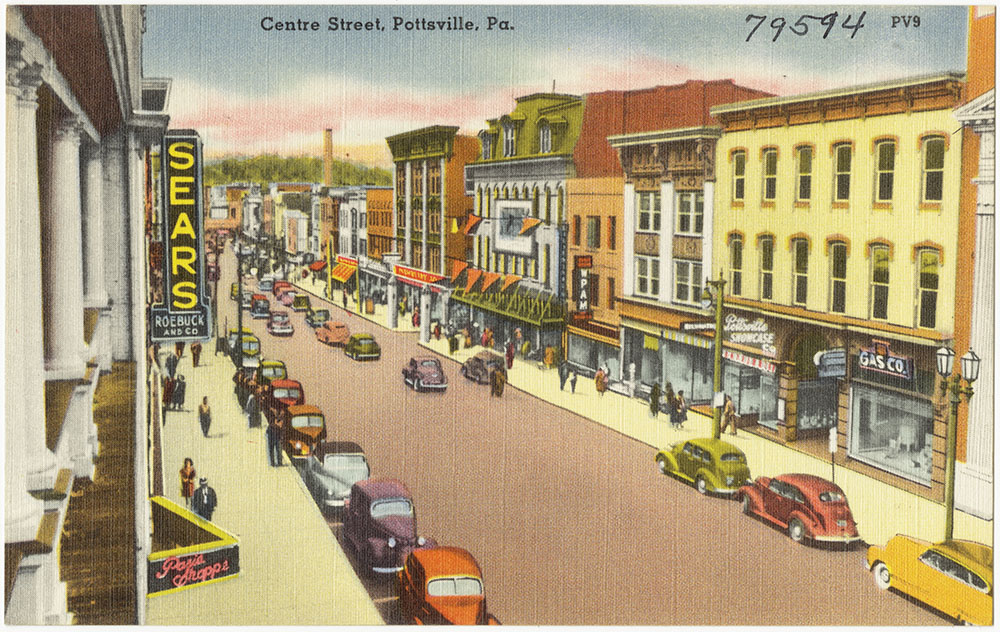

A postcard of Pottsville, Pennsylvania, circa 1930-45 (Digital Commonwealth/Boston Public Library/Tichnor Brothers Collection)

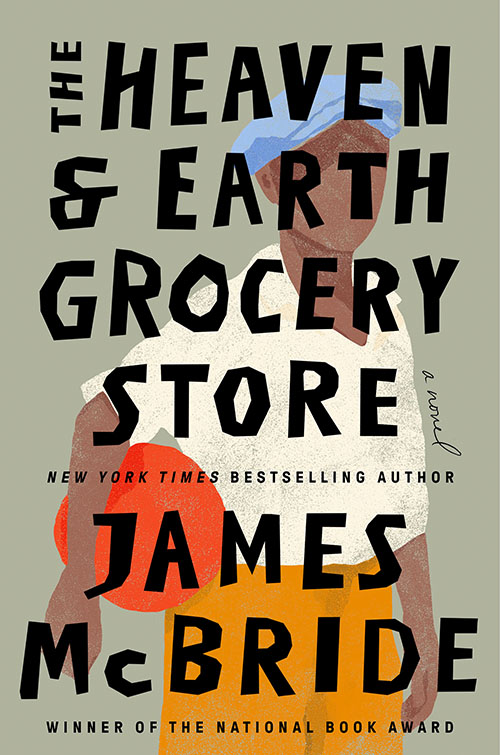

The most shocking moment in James McBride's rollicking new novel is not when a skeleton turns up at a "murder scene" on the first page.

It's not when a ghost materializes and hastens a gruesome stabbing, or even when a "pasty-faced Presbyterian" doctor — and Ku Klux Klan supporter — rants about being "replace[d]" by "the Jews, the Negroes, the Greeks, the Mennonites, the Russian Orthodox," in 1930s Pottstown, Pennsylvania.

The most shocking moment in The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store is when the wizardly McBride steps out from behind the curtain.

Having gathered his melting-pot cast at a wake, McBride digresses, pondering a day when "the glorious tapestry of their history" will be "boiled down to a series of ten-second TV commercials," or fit onto "devices that fit in one's pocket ... a device that children of the future would clamor for and become addicted to ... that fed them their oppression disguised as free thought."

Whatever your thoughts about smartphones, history or diversity, the point is that you never quite know what you're going to get from McBride — book to book, even page to page. You can make educated guesses. You'll get a chorus of voices, torrents of rich language from vivid characters. And God will be one of them.

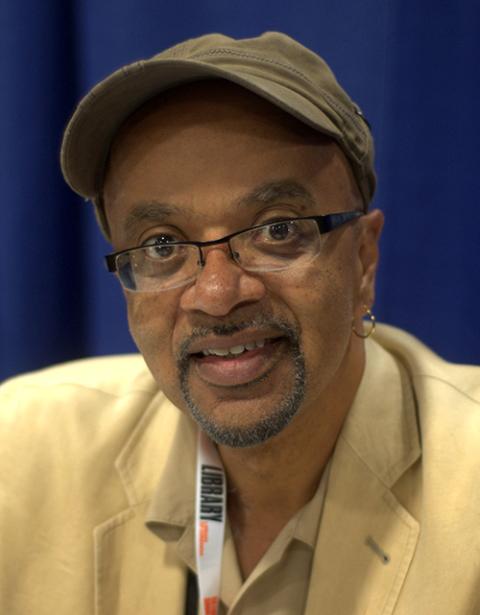

James McBride, author of The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store (Wikimedia Commons/Avery Jensen)

After all, the title of McBride's best-selling debut memoir, The Color of Water — about his sprawling, biracial, Christian and Jewish, Northern and Southern family — comes from his mother's response when young James asks "whether God was black or white." And McBride's second book, the World War II novel Miracle at St. Anna, is set in motion by an object resting on a table as if "God had placed it there, which He, in fact, had."

It's also fitting that a club called "Fatty's Jook" in McBride's newest release has a window sign reading, "Fun Inside." Because despite serious subject matter, you can expect a good laugh when you pick up a James McBride book.

Ultimately, we should think of McBride as a mystery writer in the most literal sense: He keeps us guessing.

McBride's title comes from "the sole Jewish grocery in Chicken Hill," operated by a salty, loving immigrant named Chona, whose husband, Moshe, fills his pockets doing what local bigots won't: catering to newly arrived African Americans fleeing the apartheid Jim Crow south.

The Color of Water fans will see connections here in Heaven & Earth's immigrant shopkeepers and nosy neighbors, its racial and sexual violence. Which begins to explain why McBride's tale starts off with a skeleton "at the bottom of an old well off Hayes street." It's his way of opening a door to the skeletons in our national closet.

Advertisement

McBride manages to confront these harsh realities in prose that sings and swings (he is an accomplished jazz musician, after all). If his routes to plot development are occasionally meandering, they are also scenic, bursting with color and energy.

A fight ensues after a character "balled up his fist ... and I mean that white boy reached back and sent that big fist of his rambling through four or five states."

Another conflict revolves around a boy named Dodo, who can't see or hear. Rumors circulate that a "man from the state ... gonna carry Dodo off to a special school," but Chona will hear of no such thing.

The ensuing showdown veers from caper to thriller, at the center of which are secrets, violence, skulduggery and ... water. Meaning Heaven & Earth also has a fair bit in common with the noir classic "Chinatown."

Doc Roberts may march with the Klan. Yet to many locals, he's the "kind of man whose bespectacled countenance belonged on breakfast cereal boxes." At least until the search for Dodo intensifies, and Doc crosses paths with Chona.

Ultimately, we should think of James McBride as a mystery writer in the most literal sense: He keeps us guessing.

Overall, McBride constructs these various conflicts while avoiding the kind of Manichean angels and demons that flatten many social or political novels. Just as McBride's irreverence never feels crude, his reverence rarely veers off into stuffy sanctimony.

Moshe and Chona are American dreamers, but so is a Polish American named Plitzka, who partners with a sneering Doc Roberts, as well as another character, described as a "frightening mobster."

Dodo's youthful innocence may seem Christlike, but the provocative moniker "Son of Man" is reserved for a far more dangerous character.

"It's not wise to mix things the way they do here in America," a character warns, sounding a bit like a Ku Kluxer. But he's just another dreaming immigrant — one unwittingly foreshadowing a literal (and very consequential) mix-up for Doc Roberts involving parade costumes.

In all its heart and heartbreak, faith and filth, diversity and absurdity, Pottstown is America to James McBride, though not so much for Moshe, who aspires to move to a more respectable neighborhood. "Where the Americans are," he says.

To which Chona replies: "America is here."