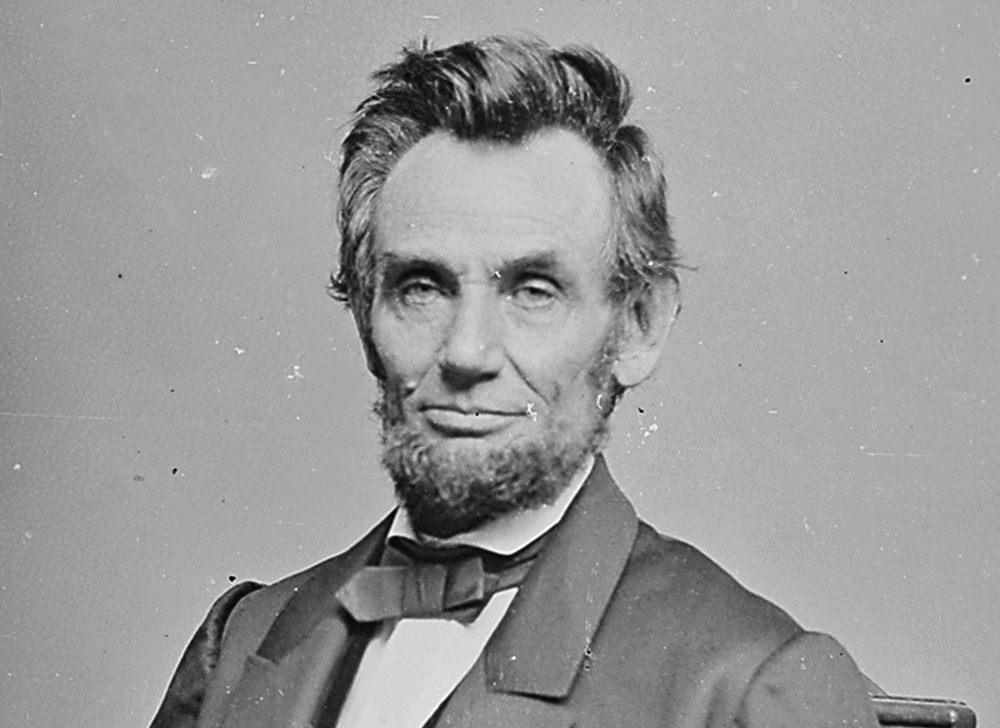

President Abraham Lincoln, photographed by Mathew Brady during the American Civil War (U.S. National Archives)

These days, a noisy faction insists on the ardent Christianity of America's past leaders, as well as the supposed obvious compatibility of devout faith and unfettered capitalism. This faction, I'm afraid, has not likely read much about their revered Abraham Lincoln.

In his thoughtful new book, Lincoln's God: How Faith Transformed a President and a Nation, Joshua Zeitz writes a compelling chronicle of Lincoln's evolving relationship to faith against a backdrop of events that influenced the Great Emancipator as much as he influenced them. Such a portrait of young Lincoln in particular, who "studiously avoided mixing religion and politics," is timely and provocative — at least for readers willing to engage in the kind of earnest reflection to which the former president was so dedicated.

A friend to the former president once bluntly described Lincoln as an "infidel," an "unbeliever in Christianity." But by the time John Wilkes Booth fired his revolver, Lincoln had wrestled with the best and worst angels of his nature (and that of his nation, too), amid a widening gyre of bondage and liberation, war and peace, to discover some semblance of divine order.

From the beginning, Lincoln was a misfit, an ambitious young man who clashed with his father in 1820s Indiana and Kentucky. Young Abe connected Thomas Lincoln's financial struggles to a blind faith in predestination and fled home around age 21, never to return — not even when his father died.

Lincoln settled in Illinois to establish a law career, the foundation of which, he said, would be "cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason."

Conflicts and complications ensued for both the future president and his country. Lincoln was admitted to the Illinois bar and elected to the state House before serving a single congressional term from 1846 to 1848.

While Jacksonian Democrats were the rural Midwest's favored political party, Lincoln gravitated to the rival Whigs — no surprise, given his contrarian streak — despite their close association with Christian social reform movements.

The Whigs had disintegrated by the 1850s, yet Lincoln again gravitated to a coalition deeply influenced by faith. What Lincoln did share with these prominent Christians was an opposition to slavery, which was "central to the new Republican party," notes Zeitz.

But Lincoln didn't fit in there. The truth is that even into his 40s, Lincoln — a "freethinker ... loose-lipped in his disregard for organized Christianity," as Zeitz puts it — was ill-suited for public life.

Lincoln wrestled with the best and worst angels of his nature (and that of his nation, too), amid a widening gyre of bondage and liberation, war and peace, to discover some semblance of divine order.

Ironically, Lincoln's connections to a "phalanx of committed Christian antislavery activists" left him open to charges that he and his allies were "narrow-minded ... bigoted [and] socially coercive," in the words of rival Stephen Douglas.

In a book about "how faith transformed a president and a nation," we should probably hear more about the profound demographic changes initiated by Catholic immigration during this era, even if Lincoln admirably rejected the nativism of many Whigs-turned-Republicans. Poverty, race, labor and urban violence were just some of the complex topics that got tangled up with religion and politics in pre-Civil-War America. The result was "the alignment of church, state, and [Republican] party."

The onset of war only accelerated the religious evolution of both the nation and Lincoln. Zeitz's insightful digressions explore religiously indifferent soldiers who found faith on the front lines and religious Americans who "refined their ideas about heaven."

Less than a year into the bloodshed — recklessly initiated by Lincoln himself, critics charged — Willie Lincoln, Abe's son, died from typhoid at age 11.

In the face of such Jobian torment, Lincoln looked to religion "to make sense of the tragedy that befell his family."

Many Americans similarly looked to faith for their own comfort and guidance in such a trying time in history. Others, though, found something closer to vengeance.

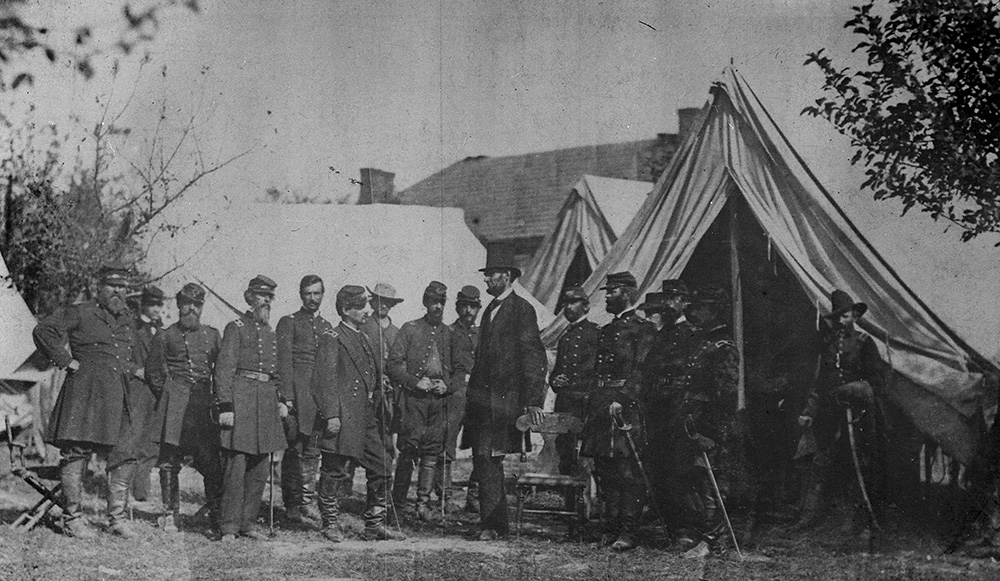

President Abraham Lincoln and his generals, photographed by Mathew Brady after the Battle of Antietam in Maryland in 1862 (U.S. National Archives)

In the fog of war, Confederates were dehumanized, Zeitz argues, while violence became sacred and religious impulses wrathful. This marked not just "a jarring break with Christian pacifism," but seemed to justify a new "vision of state authority and state-sanctioned violence."

By 1864, a delegation representing nearly a dozen Protestant denominations proposed an amendment to the Constitution's preamble to recognize "Almighty God as the source of all authority and power in civil government," and "the Lord Jesus Christ as the Ruler among nations," which would surely have had some fascinating ramifications over the next 150 years, had it passed.

Lincoln somehow navigated these swirling forces nimbly. He spoke of the nation's trials in biblical terms and with divine overtones, while avoiding the troubling "certainty that God favored the North."

To Zeitz's mind, Lincoln had "reverted… to the fatalism of his father's religion," a claim that may be a touch too neat, as is Zeitz's assertion that the "Civil War had blown ... away" the Jeffersonian wall of separation between church and state.

Advertisement

What is clear is that after his son's death, four years of war and two centuries of slavery, Lincoln had come to believe that, in Zietz's words, "the scope for human agency was limited."

Then, on Good Friday 1865, the president made his way to Ford's Theatre.

After Lincoln's death and the Civil War, a new kind of religious zealotry ran — and still runs — amok. This is meant to wrap up Lincoln's God, to offer a thread to future narrative historians. So the author's decision to opt out of addressing the popular claim that progressives have made social justice a new religion for a secular age is forgivable.

The same can't quite be said for his broad assertion that, in the defeated Confederacy, "Protestantism retreated ever inward, focusing on the business of saving souls, one by one, keeping itself aloof from the business of government and politics." Decades of Jim Crow and Ku Klux Klan crucifixes — not to mention modern debates over reproductive and LGBTQ+ rights — beg to differ.

In the end, the most memorable observation in the book comes from Herman Melville, who observed roughly two centuries ago that future religious Americans would prefer to base their passionate convictions on "nothing but their own eyes."

Which might have worked out, if most Americans used their eyes with the rigor and sophistication of a Lincoln, rather than to selectively doom-scroll the most extreme corners of social media — or, for that matter, the Old Testament.