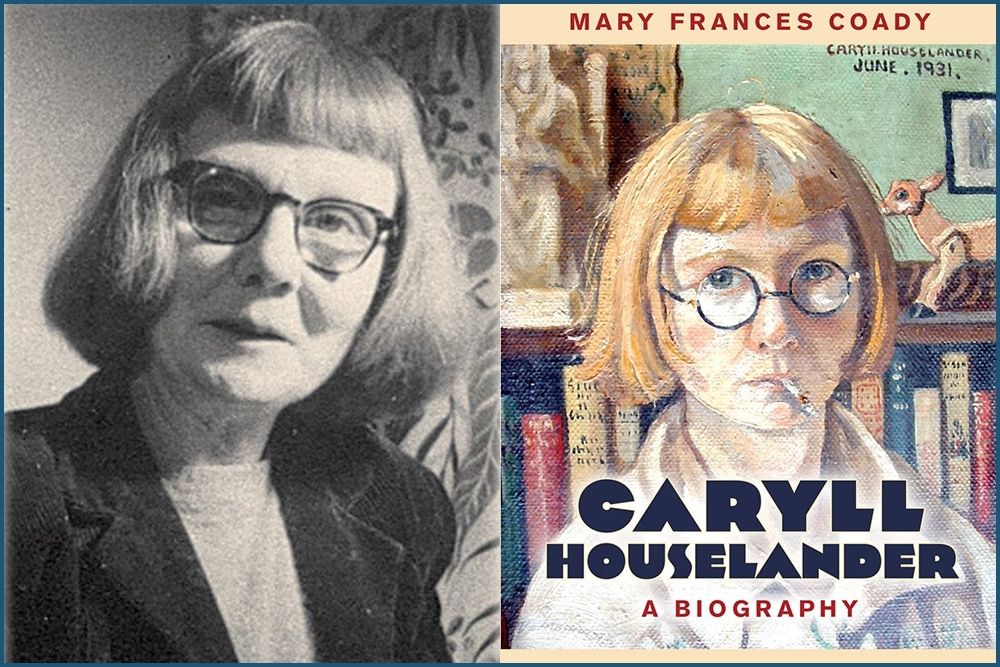

Author Caryll Houselander is pictured in an undated photo beside the cover of Caryll Houselander: A Biography, written by Mary Frances Coady. (CNS; Orbis Books)

She was surely the oddest Catholic author who ever lived. She went about London with her face powdered dead white, in vivid contrast to her natural carrot-colored hair, chopped off in front just above her eyebrows. Short in stature, she peered at the world through thick, round eyeglasses. She cursed like a longshoreman, liked to drink gin, and was rarely seen without a cigarette dangling from her lips.

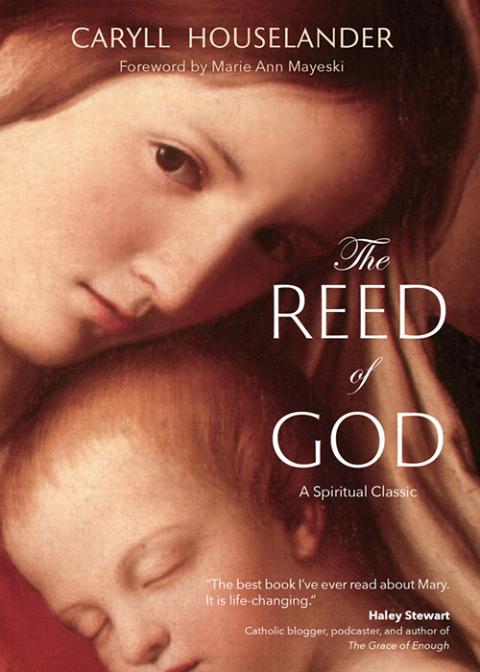

And yet Caryll Houselander inspired thousands with her urgent, compelling prose during and just after World War II. Her book The Reed of God is a lovely piece of Marian spirituality, still in print almost 80 years after publication. Houselander was especially popular in the United States where most of her books first appeared, since her publisher's London office had been destroyed in the Blitz.

In Caryll Houselander: A Biography, Mary Frances Coady has done an excellent job of bringing Houselander back to life — a life particularly difficult to get a handle on because Houselander, like her mother before her, could be careless about facts when telling her own story. Her truncated autobiography, A Rocking Horse Catholic, was not initially distributed in Britain because her family complained of its errors and omissions.

But Coady sorts it all out in this factual, carefully-researched biography. She tells of Houselander's early years, the child of mismatched parents who divorced when Houselander was 11. She was a sensitive, artistic girl, totally unlike her impulsive mother, Gertrude. She spent her youth in convent schools, where she was sometimes considered a "freak" for her looks and mannerisms; but where she flourished.

After moving to London with her mother and older sister, she attended art school for a time and went through a bohemian period, doing odd jobs to sustain herself. She decided the Catholic Church was hypocritical and walked away from it when asked to pay a fee for sitting in a pew.

Advertisement

Coady is especially sensitive to Houselander's religious development. She was baptized as a young girl, went through an intensely devout phase, left the church briefly in early adulthood and came back after a vision in the London subway in which she saw Christ in all the travelers there. From that point on, Houselander's books elaborated on the theme of Christ present, not just in saints; but in all persons — and in human history generally.

As she wrote to wartime Londoners, "Because he [Christ] has made us 'other Christs,' because his life continues in each of us, there is nothing that any one of us can suffer which is not the passion he suffered." In this way, her intuitive religious vision anticipated Pope Pius XII's encyclical on the "Mystical Body of Christ."

Houselander spent her early career as a struggling artist and woodcarver. Her first writing appeared in devotional periodicals, including The Grail magazine, where it was spotted by Frank Sheed and his wife Mazie Ward. Ward became a devotee of Houselander, constantly encouraging her to undertake new projects — including a novel late in life, and a treatise on guilt, neither of which was successful. But Houselander's spiritual writing, now often overlooked, was devoured on both sides of the Atlantic.

"Because he [Christ] has made us 'other Christs,' because his life continues in each of us, there is nothing that any one of us can suffer which is not the passion he suffered."

— Caryll Houselander

Ward also produced the first biography of Houselander shortly after her early death from cancer in 1954. Yet is not considered to be a reliable source because Ward accepted her friend's stories at face value and prudishly glided over Houselander's youthful affair with a British spy who went by the name of Sidney Reilly. Houselander was devastated when Reilly left her for another woman. She doesn't mention it in her own autobiography, but for years afterward she kept Reilly's photo at her bedside and even adopted Reilly's first name, calling herself Sidone, or "Sid."

Coady's book restores Houselander to her rightful place in the history of spirituality, covering Reilly and all the other characters in Caryll's colorful, fully-lived existence — including the living arrangement of "Gert," her motorcycle-riding mother, with Iris Wyndham and her hoyden daughter Joan.

For those who already know Houselander and those who want to meet her, this is a book for you.