Isaac Hawkins Hall, on the campus of Georgetown University, is seen in this file photo from April 4, 2017. Previously known as Mulledy Hall and later Freedom Hall, it was renamed in 2017 for one of the 272 enslaved men, women and children sold to plantation owners by Georgetown's Jesuit community in order to finance the school. Hawkins was the first enslaved person listed in the sale documents. (OSV News/Tyler Orsburn, CNS)

It is a striking irony of history that the U.S. Supreme Court should have found affirmative action in college and university admissions unconstitutional just when U.S. institutions of higher education are beginning to reckon in earnest with their entanglements in the North American slave economy.

As the historian David Blight has remarked, "For so long, at many campuses, including my own, Yale, there have been silences in the books but not in the archives." Brown, Harvard, the University of Virginia, and Yale, among others, have commissioned studies to crack open the archives, finding that, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor put it in her dissenting opinion in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, "Slavery and racial subordination were [from the start] integral parts of the institution's funding, intellectual production, and campus life."

Georgetown University's reckoning with its entanglements in slavery may be the best known case, thanks to a 2016 New York Times article by Rachel Swarns, then a reporter for the Times, now a contributing writer to it and a professor of journalism at New York University. Swarns' article and subsequent reporting brought national attention to the mass sale in 1838 of 272 men, women and children enslaved by the Jesuits in Maryland. The proceeds, ultimately around $4.5 million in today's dollars, shored up Georgetown's shaky finances and enabled the Jesuits to begin "transforming themselves," in Swarns' words, "from an order known as one of the largest slaveholders in Maryland to one that would become synonymous with Catholic education."

For example, the College of the Holy Cross was founded in 1843, under the name Worcester College. Its founding president was Thomas Mulledy, the former Georgetown president (1829-1838 and later 1845-1848) and Maryland provincial (1837-1840), who along with William McSherry (provincial 1833-1837, president of Georgetown 1838-1839) willed the mass sale to happen, despite the cries of Black people wrenched from family and over the strong objections of some fellow Jesuits. Two buildings on Georgetown's campus bore Mulledy's and McSherry's names until 2015.

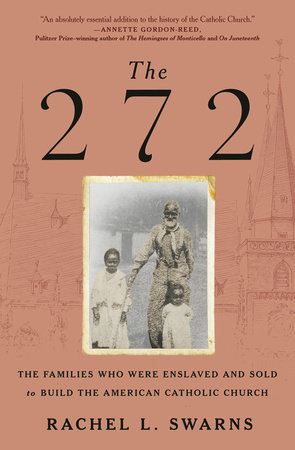

Swarns has synthesized her findings into a new book, The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church. The subtitle of Swarns' book indicates the ambition of its argument. According to Swarns, "Without the enslaved, the Catholic Church in the United States, as we know it today, would not exist." After all, "The priests in Maryland, who relied on the proceeds derived from slave labor and slavery, built the nation's first Catholic college [Georgetown, 1789], the first archdiocese [Baltimore, established as a diocese in 1789, then as an archdiocese in 1808], and the first Catholic cathedral [Baltimore, 1821]." And then "the mass sale of 1838," toward which Swarns' story builds, "would prove to be a critical turning point," enabling the Jesuits to expand into "the young nation's rapidly growing urban centers." (As an aside, the Society of Jesus had been suppressed in 1773, partially restored in the U.S. in 1805, and fully restored in 1814.)

The 272 aims to be a contribution to what Swarns calls "public memory," from which, she submits, the history of Catholic slaveholding "had largely faded" until recent years. Her book is no mere rehashing, however, of other scholars' work, but draws from original archival research.

'Without the enslaved, the Catholic Church in the United States, as we know it today, would not exist.'

—Rachel Swarns

Swarns primarily "follows the trail" of the Mahoney family, beginning with a free Black woman named Ann Joice, who arrived in Maryland around 1676 as a teenager and an indentured servant to the Catholic Lord Charles Calvert, then the proprietary governor of Maryland. When Calvert returned to England in 1684, he sent Ann to the home of his relation Colonel Henry Darnall, also a Catholic, who "seized her indenture papers … and set them on fire," effectively converting her into a slave at "a time when blackness and slavery were quickly becoming synonymous."

As Swarns admits, "the trail goes cold" with some frequency, but she picks it up with Ann's descendant Harry Mahoney, on the Jesuits' St. Inigoes plantation in southern Maryland. (Íñigo was the birthname of Ignatius of Loyola, as well as an 11th-century hermit, monk and saint from Ignatius' Basque country.) For Harry's quick thinking during a British raid on St. Inigoes in the War of 1812, Swarns recounts, the priests "made a pledge to him that [the] family would cling to for decades: They promised that he would never be sold."

Advertisement

As it happened, Harry was not sold in the 1838 mass sale, but members of his family were, rounded up and "treated as animals in every respect," according to an outraged Jesuit, then shipped down to Louisiana, where they became the "assets to be bought, sold, mortgaged, and used as collateral" of former Louisiana governor and onetime U.S. congressman Henry Johnson and his business partner.

The last four of Swarns' 14 chapters broadly sketch the aftermath of the mass sale. Official Catholic thinking about Black enslavement began to change in 1839, when Pope Gregory XVI issued an apostolic letter condemning the slave trade. Swarns notes that Bishop Benedict Fenwick of Boston suspected that the Maryland Jesuits had been warned in advance of the pope's condemnation, perhaps explaining Mulledy and McSherry's haste to execute the sale of the 272. In 1862, Archbishop John Baptist Purcell of Cincinnati "condemned 'the sin of… holding millions of human beings in physical and spiritual bondage,' '' only to be roundly criticized by Bishop Martin Spalding of Louisville, who wrote to Rome in opposition.

Rachel L. Swarns is the author of The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church, published by Random House. (OSV News photo/The Catholic Standard/Lisa Guillard)

Rome sided with Purcell, but quietly: as Swarns writes, its "new stance on slavery … would not be disseminated as Church doctrine for years." Remarkably, Mahoney descendants in both Maryland and Louisiana did not give up on Roman Catholicism, but made significant contributions to it. For example, one joined and eventually led "the nation's first order of Black nuns, the Sisters of the Holy Family." In Swarns' formulation, their faith "did not belong to [the] hard men" who had exploited them.

The book's epilogue brings readers back to our contested present, detailing efforts by Georgetown, the Jesuits, and the descendants of the 272 to come to terms with this difficult history. Swarns quotes the historian Craig Steven Wilder's observation that " '[i]t's the religious institutions that have started to lay out a path … toward restorative justice. … It's much harder for religious institutions to be silent on the moral implications of their own history.' "

Jesuit Fr. Timothy Kesicki, then president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, speaks at a Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition and Hope April 18, 2017, at Georgetown University. The liturgy was held to acknowledge and seek reconciliation for the Jesuits' 1838 sale of 272 enslaved men, women and to help secure the financial future of Georgetown University. (OSV News/Catholic Standard/Jaclyn Lippelmann)

As a start, in 2016, Georgetown extended "preferential status in the admissions process to descendants," similar to legacy status for children of graduates. In 2017, the university and the Jesuits formally apologized for the sins of slaveholding. In 2019, Georgetown pledged that it would raise $400,000 per year to benefit the descendants of the 272, and in 2021 the Jesuits pledged to raise $100 million for a foundation to benefit the descendants and to promote reconciliation initiatives. Notably, Georgetown took the lead in an amicus brief submitted for Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard by a host of Catholic colleges and universities in support of affirmative action.

It is also noteworthy, however, that the foundation has struggled to raise funds: as of August 2022, only $180,000 on top of the $15 million that the Jesuits originally contributed. Like it or not, donors may wonder why they should give money to the foundation rather than, say, Jesuit colleges and universities seeking today to serve a racially and economically diverse student body and not directly implicated, like Georgetown, in the sins of slavery.

Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr., who wrote the judgment in the Supreme Court's first admissions affirmative action case, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978, characterized the goal of "the remedying of the effects of 'societial discrimination' " as "an amorphous concept of injury that may be ageless in its reach into the past." In contrast, Swarns' book clearly outlines the injuries suffered by the 272. She thereby forces, though does not resolve, the hard question of how to atone for the injuries passed down across the generations.