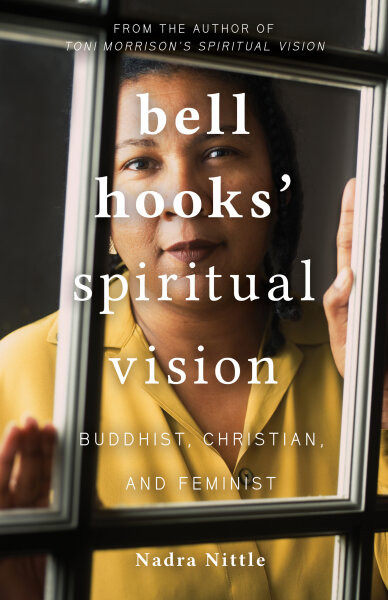

The late bell hooks is pictured at a talk in October 2014 at The New School in New York City. (Wikimedia Commons/Alex Lozupone, CC by SA 4.0)

When I think of bell hooks, I think of a fierce, tenacious, unapologetic cultural critic and feminist theorist; a literary giant in the 20th and 21st century; a writer and scholar deeply invested in political activism. Nadra Nittle's new book, bell hooks' Spiritual Vision: Buddhist, Christian, and Feminist, affirms all these things, but also transcends them in offering an account of hooks' thoughtful engagement with her interior life.

Nittle honors the complex and dynamic character of the late bell hooks by intimately examining her spiritual life as a self-described Buddhist Christian, recognizing hooks first and foremost as a woman of faith before her identification as feminist, writer or scholar. Nittle argues that it is essentially hooks' vision as a Buddhist Christian that lays the foundation for the conviction in her writings, ultimately bridging her feminist approach to spirituality with her political activism.

The writer known as bell hooks — whose pen name honors her great grandmother, Bell Blair Hooks — never authored any of her work under her birth name, Gloria Jean Watkins, as part of her praxis of nonattachment to identity. Her trademark commitment to lowercase all the letters in her name stemmed from a "desire to direct attention to her work rather than herself," a desire rooted in the virtue of humility that her Buddhist Christian spirituality emphasized. Nittle asserts that "Although Christianity is a monotheistic religion and Buddhism is a nontheistic one, they both focus on compassion, personal transformation, action, and a call for followers to distance themselves from materialism and worldliness."

The writer grew up in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, one of seven children in a fundamentalist Christian family, within which she suffered emotional and physical abuse throughout her childhood. "Audacious, intelligent, and willful, Gloria suffers in a family that doesn't know what to make of her giftedness," writes Nittle. "Powerless during the era of segregation, and enslavement before then, some Black parents dehumanized their children just as a racially stratified society had dehumanized them." Her childhood was about survival; it was not until after she left home that she was able to find safe places for her creativity to flourish, which then led to the ignition of her passion for child liberation theology.

As part of her lifelong suspicion of "imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy," hooks believed that "truly keeping children safe in homes requires ending patriarchal domination." To hooks, children are not the future: They are the present. They are the right here and the right now, and their voices must be heard.

Advertisement

Nittle offers stories from hooks' youth of exemplary role models that grounded her childhood despite the abuse in her home. There is Miss Erma, an unapologetic congregant at hooks' church who validated hooks as an orator; Daddy Gus, the maternal grandfather who heavily influenced hooks' "development as a nonviolent feminist and anticapitalist believer"; and an unnamed disabled deacon at her church who exemplified Christlike patience.

These exemplars served as extensions of the incarnation to hooks and grounded her in the midst of an unstable childhood, helping her to "recognize her self-worth" and to realize that "she didn't need to conform." It is through these local, holy saints in her life that she was able to see herself in a way that validates the self, while simultaneously decentering the self. She would later see this aligned with the Buddhist commitment to "a spiritual practice that emphasizes self-actualization, a development that occurs when a person releases the idea of self."

This spiritual vision as a Buddhist Christian not only influenced hooks' commitment to child liberation theology, but also to feminism. However, Nittle notes, hooks refused to identify herself as a womanist. "She argued that Black women didn't need a separate term to describe themselves in the feminist movement because the term she coined — 'imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy' — captured the interlocking forms of oppression that target them."

Author and social activist bell hooks (Newscom/KRT/Donna Dietrich)

Nittle offers a thoughtful counterargument to hooks' nuanced claim, stating that in her opinion "this stance ignores the Black women who felt that feminism didn't address their particular needs." Although deeply aware of the imbalance between Black and white women within the feminist movement, hooks believed that "it was more important to stand with women who have 'dared to claim feminism' than to claim womanism."

Lastly, hooks' Buddhist Christian framework greatly influenced her philosophy on the concept of love, which she defines as "an action that nurtures one's own or another person's spiritual growth." One of hooks' most popular books, All About Love: New Visions, was originally published in 2000. After her death in December 2021, interest in this book spiked, and it appeared on The New York Times bestseller list in both 2021 and 2022.

Notably, this was in the midst of the pandemic, as yearning for meaning and spirituality exploded, and hooks' writing served as solace for many people. Her critique of how Americans fail to prioritize nurturing their spiritual life "because individualism, capitalism, and power compete for their attention in a society that values material over the spiritual" resonated with readers. According to hooks, love should challenge the capitalistic framework. Nittle captures the wisdom of hooks, writing, "Intellect is not remotely as important as love is. … One should engage the spiritual consistently."

Nittle's book offers a blueprint to the interior life of bell hooks, reflecting on how a dedication to her Buddhist roots strengthened her relationship with Christianity, and vice versa.

Ultimately, Nittle's book offers a blueprint to the interior life of bell hooks, reflecting on how a dedication to her Buddhist roots strengthened her relationship with Christianity, and vice versa. For hooks, Buddhism, Christianity and feminism work together, not against each other. Activism is a spiritual practice that requires a personal asceticism — a relationship to God — and this makes all the ecclesiological difference.

Nittle references theologian LaRyssa D. Herrington's 2022 NCR article, in which Herrington wrote that hooks believed that a commitment to spiritual practice "demands conscious effort where we are willing to unite the ways we think with the ways we act." Her spirituality serves as the foundation for an accountable, practical type of love; a love that stems from the interior life matching the active life.

At large, hooks was an incredibly complex and nuanced woman and wanted to be remembered as such; Nittle gives readers space to dance in these nuances alongside, and with, hooks.