"The Plague in Rome," an 1869 painting by Jules Elie Delaunay (Artvee)

A mysterious new illness arrived from the East, killing young and the old. The rich fled cramped cities as doctors desperately tried new but ultimately useless remedies. The economy faltered. But among this chaos, some managed to show charity and compassion to their sick and dying fellows.

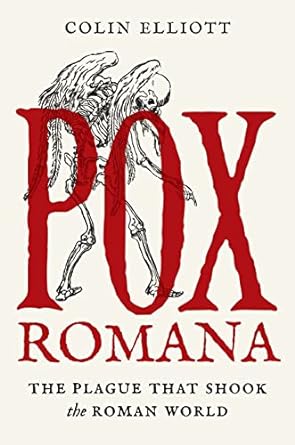

This was the world of the Roman Empire in the late second century. In his new book, Pox Romana: The Plague That Shook the Roman World, Colin Elliott looks at the effects of the Antonine plague on the Roman world and its effects on an empire already beginning to crumble under its own weight. He also looks at how one of the empire's minority religious groups — Christians — both cared for the sick in the face of the plague and were persecuted by scared people trying to do whatever they could to keep social order.

The book's title is a play on Pax Romana, the famous period of peace in Rome considered to have lasted from circa 27 B.C. to 180 A.D. Previous scholars have suggested that this peace ended solely due to the Antonine plague. Elliott's argument is that the empire was already struggling. He describes the vast filth and distemper of the preindustrial world: the grimy bathhouses, the smoke-filled apartment buildings and the almost complete lack of useful medicine. It offers an interesting look into the often romanticized world of the supposed peak of the Roman Empire.

Grain harvests in the years prior to the plague had been poor. Much of that grain was used to prop up the imperial capital itself — the world's largest city at a million people — that could barely feed its denizens, even in a good year. Rural people, many of them enslaved, went hungry as large grain taxes were imposed to feed urban citizens. The city's poorest were not citizens, and went hungry too. It was a society already teetering on the edge. Plague was an accelerant on a fire that had already started to burn.

That large army necessary to enforce the Pax Romana also meant large numbers of men marching long distances, far further than the tightly constrained radius around a village a peasant would travel. Disease spread thousands of miles from the empire's eastern borders in Mesopotamia to its western end in Britain and everywhere in between.

"Plague in an Ancient City," a circa 1650-1652 painting by Michael Sweerts (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Something else that had traveled in the previous century and a half from its origins in the eastern end of the empire was a new religion: Christianity. Christians were seen as suspicious due to their refusal to participate in the Roman state religion. Romans, whether they believed in it or not, were expected to offer sacrifices to the gods; to not do this was to potentially provoke divine wrath. Christians were seen as atheists, and theories about their horrifying behavior spread, with the emperors' teacher saying Christians ate infants and had incestuous orgies.

Elliot acknowledges there are no texts directly linking the Antonine plague with anti-Christian persecutions, but there is plenty of documentation linking fear and unease, particularly around disease, with mob uprising against Christians. This was not yet state-driven (indeed, the state would sometimes try to suppress it), but driven by the populace. The theologian Tertullian, writing at the end of the plague years, would comment that Christians were blamed for every disaster, with the immediate response being to throw Christians to the lions.

Christians were different from other Romans, not only because of what they did not do but because of what they did: caring for the sick, the poor and the dead, not solely out of the sense of noblesse oblige of euergetism but as a religious tenet. They had a community of believers that helped each other that was distinct from the patron/client relationships that characterized Roman society. This reflected their religious belief in a God who freely gave grace, and whose son sacrificed himself for all, which also contrasted with the transactional nature of Roman state religion.

Advertisement

Pox Romana is a well-researched book that not only draws heavily on surviving textual records, both writings as well as other data like censuses, but also on archaeological findings (particularly related to coinage) as well as climatological evidence. It gives enough details without getting bogged down in excessive description of military formations or aqueduct construction.

One frustrating part of this otherwise stellar book is the author's unnecessary and often strange digressions into modern politics. It would be difficult to publish a book about a pandemic in 2024 and not mention COVID-19 at all, but at times it feels like the author is using his book to forward a particular political and economic agenda.

Elliott is rightly critical of the poorly functioning Roman system of grain taxation, but then says our modern ability to buy cheap bread is a result "not of political planning but of voluntary trade, technology, and market integration." It belies an ignorance of modern agricultural policy, and other criticisms of state power and taxation make it seem like he is unaware his own livelihood as a state university professor is wholly dependent on taxpayers.

He writes about a later Roman plague where Romans were required to show papers saying they sacrificed to the state gods by talking about how they had to "contribute to collective inoculation through ritual worship" and that this was a "passport" that verified they had "duly sacrificed and … therefore immune from blame for the woes of an evil age." There is railing against Soviet collective farms and referring to rural bandits as "deplorables." Such phrasing distracts from what is otherwise an engaging read.