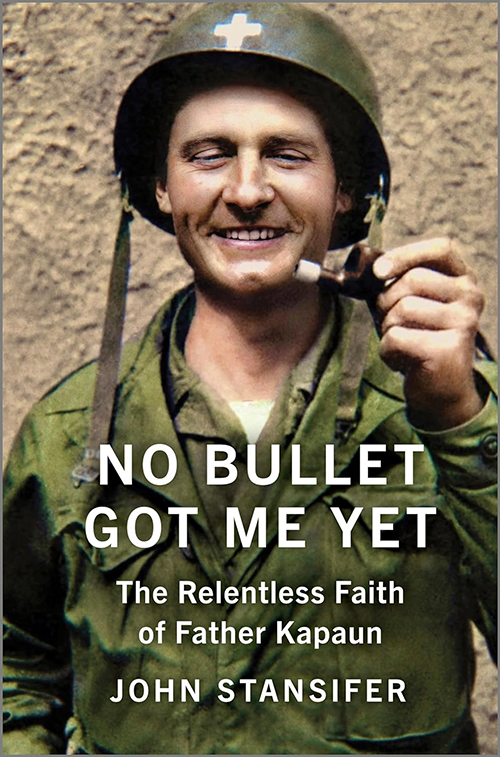

U.S. Army chaplain Fr. Emil Joseph Kapaun, who died May 23, 1951, in a North Korean prisoner of war camp, is pictured celebrating Mass from the hood of a jeep Oct. 7, 1950, in South Korea. (CNS/Courtesy U.S. Army medic Raymond Skeehan)

No Bullet Got Me Yet is a collection of letters written by, to and about Emil Kapaun, a Catholic priest and army chaplain in the Korean War. Archived by the Father Kapaun Guild, the letters comprise the record of Kapaun's heroism in the 1st Cavalry Division on Pusan Perimeter in the summer of 1950 and the sacrificial service he provided fellow POWs after he was captured by Chinese troops in November. He died at POW Camp 5 in May 1951 and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by President Barack Obama in 2013.

Stansifer's narration includes Kapaun's farm-family background in Kansas, his socialization into the Catholic faith — "the warp and woof" of family life — and the educational track that led him to the priesthood. From boarding school at Conception Abbey near Kansas City in 1936, he went to Kendrick Seminary in St. Louis. By the time he served his first Mass in 1940, Germany had annexed a part of Czechoslovakia and the country was hearing war drums from Europe.

Fr. Emil Kapaun, a U.S. Army chaplain, is pictured in an undated portrait. (OSV News/St. Louis Review)

But Kapaun wasn't feeling the vibe. The Versailles agreement ending the First World War had robbed Germany of its rights and territory, he wrote in a letter to friends, and Hitler wanted to take them back. The Americans who fought in Spain against Hitler's ally Francisco Franco were "fighting for the Communists against the Christians," wrote Kapaun — a cold-war premonition that would take him to Korea.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, changed Kapaun's views on the Second World War. Referred to as "pagans" in a letter he wrote after the raid, the Japanese had attacked "God's country," calling him to service. After a stint as an auxiliary chaplain on a local air base, Kapaun entered training for the army chaplaincy in August 1944. In March 1945 he deployed to the China-Burma-India theater of operations.

Kapaun was discharged in 1946 but was drawn back to the army in 1948. By that time, he had assimilated to military life and the fight against the rising tide of godless communism was calling. In January 1950 he shipped out for occupied Japan, where Gen. Douglas MacArthur had requisitioned "ten thousand Christian missionaries and a million Bibles to complete the occupation of this land." There, Kapaun was assigned to the 8th Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division, the unit he embarked with on a Landing Ship Tank (LST) for Pusan, South Korea, in July 1950.

The record of Kapaun's heroism in the 1st Cavalry Division began in the battle of Taegu on the outer boundary of the Pusan Perimeter in August, when he and his assistant risked enemy fire to rescue two wounded men who had been abandoned by medics; for that, he would be awarded the Bronze Star for bravery. The landing of United Nations troops with U.S. Marines at Inchon allowed Kapaun's unit to move north.

Advertisement

The letters collected by Stansifer describe battle after battle in which Kapaun distinguished himself. The editor's narration provides a usable outline of the war's military operations, but the letters themselves don't qualify as Korean War documentation. Collected by the Father Kapaun Guild as an amicus brief for his canonization in the Catholic Church, the letters are religiously-themed testaments to his faith and service to the anticommunist Christian mission in Korea, weaponized with its appendance to the military. "I've never known a braver man, a more devoted Christian leader, a more sympathetic listener or a better friend …" wrote a fellow chaplain. "I've prayed that he would be spared, but God rewarded him in a greater way. … He is a hero, a Saint if anyone ever was."

The provenance of the letters is sketchy. Kapaun's letters sent home during the 10 months before his capture are presumably a sample of a larger set — but how were they selected, and by whom? Other letters, quoted from secondary sources, have been pre-filtered by earlier editors and publishers. Interviews with veterans done by Stansifer, after Kapaun's 2013 receipt of the Medal of Honor, are especially problematic given the 60-year gap between their time with the priest and their memories of him.

These limitations aside, No Bullet Got Me Yet could fit on an undergraduate course syllabi with a segment on the military chaplaincy. Public historians interested in the intersection of military and religious institutions as a Cold War vector might see its value. An unnuanced period piece, the book tells us a lot about American years sometimes overlooked.