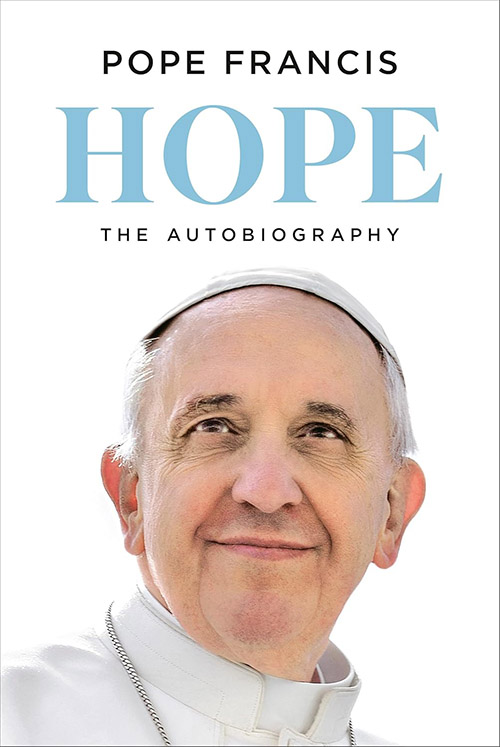

Pope Francis begins his weekly general audience in the Paul VI Audience Hall at the Vatican Feb. 5, 2025. (CNS/Lola Gomez)

From his first papal appearance in March 2013 on the balcony above St. Peter's Square, charming Italians with an avuncular purring of "Bueno sera," Francis has steered a path unlike any previous pope. Now, thanks to his newly released memoir, Hope, the story of the world that made Jorge Mario Bergoglio — and, by extension, the world leader we know as Pope Francis — is a story finally told in his own words.

Collaborating with the Italian journalist Carlo Musso, Francis dwells on his ancestral background in Northern Italy as bonds between the old country and new shaped his worldview. He ignores a number of mysteries, such as why, as pope, he has yet to return to Argentina (presently governed by a libertarian nationalist who has denounced him) and possible scandals in the Roman Curia that drove his predecessor Pope Benedict XVI to retire. Though he speaks with compassion of clergy abuse survivors, Hope ignores Vatican resistance against his own commission for protecting minors. These details await probing biographers.

Since World War II, the pope has been a moral statesman, a global diplomat for peace. Pope Pius XII was a revered post-war figure whose silence on the Nazi round-ups of Jews in Rome became an issue only after his death. Pope John XXIII as papal nuncio in Turkey during the war had helped Jews escape. "Authority is before all else a moral force," he wrote in the 1963 encyclical Pacem in Terris. "The appeal of rulers should be to the individual conscience, to the duty which every man has of voluntarily contributing to the common good." Pope Paul VI made an impassioned plea for peace at the United Nations. Pope John Paul II's stirring sermons in his native Poland, still in the grip of Communism, made him a catalyst in the fall of the Soviet Empire.

Within days of becoming pope, Francis was dogged by media reports suggesting his complicity with Argentina's dictatorship in "the dirty war" of 1976-83. In Bergoglio's List (2013), the Italian journalist Nello Scavo found a much different story in the complexities of the young Jesuit provincial's struggle to protect his divided community, while helping people escape, a reality explored in Austen Ivereigh's impressive 2014 biography, The Great Reformer.

Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, now Pope Francis, washes the feet of residents of a shelter for drug users during Holy Thursday Mass in 2008 at a church in a poor neighborhood of Buenos Aires, Argentina. (CNS/Reuters/Enrique Garcia Medina)

Francis showed a profound sense of symbolic language in washing the feet of an imprisoned Muslim girl in Rome on Holy Thursday 2013, a signal of reconciliation with Islam via the media. His first official papal trip was to the island of Lampedusa, visiting migrants who survived the treacherous Mediterranean crossings.

"When I heard the news of yet another shipwreck just a few weeks before," he reflects, "the thought kept coming back to me, like a painful thorn in my heart. … I too had been born into a family of migrants — my father and my grandparents, like so many other Italians, had left for Argentina and knew the fate of those who are left with nothing. I too could have been among the outcasts of today, so that one question is always lodged in my heart. Why them and not me?"

This cri de coeur for the world's poor is the thematic engine of Hope.

He writes of the barrio where he was raised as "a complex, multiethnic, and multicultural microcosm" in which he grew up with Jewish friends whose roots lay in Odessa "where a vast Jewish community lived, large numbers of whom would be massacred by Romanians and Nazi occupying forces during World War II. Many customers of the factory where my father worked were Jewish, employed in the textile industry, and many were our friends. Likewise we had various Muslim friends, even among boys in my group, who for us were 'the Turks' since they generally arrived with a passport from the old Ottoman Empire."

Pope Francis greets immigrants at the port in Lampedusa, Italy, in this file photo July 8, 2013. During his visit, the pontiff urged people not to be part of the "globalization of indifference" to the plight of the millions worldwide who are immigrants and refugees. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano via CPP)

Advertisement

Francis draws links between the lessons of home, church and barrio, and the spiritual rigors he embraced as a young Jesuit. He writes of his friendship as a student of 17 with Esther Ballestrino de Careaga, a 35-year-old left wing librarian exiled from Paraguay. "She gave me books to read and encouraged me to widen my knowledge with further reading" — including the Communist journal La Vanguardia. He recoiled from the execution of the Rosenbergs and the spread of American McCarthyism. "I once said that communists stole the flag from us because the flag of the poor is Christian," he reflects.

Bergoglio was a young Jesuit provincial when Esther's pregnant daughter was kidnapped. Upon her release, he writes, "She told how she had been hooded, stripped naked, beaten, how electric shocks were applied to her body" — and escaped being raped by saying she had leprosy. To help Esther evade persecution, the Jesuit agreed to carry off her library, including many Marxist texts. Esther got her family into exile, yet she insisted on returning to join protests of the Mothers of Plaza De Mayo in Buenos Aires, seeking return of their children. In 1977, "Esther was seized by political police agents in front of the church of Santa Cruz," gone forever.

He recalls a reunion with her daughters on a 2015 papal trip to Paraguay, a grace note as his thoughts trail back to wartime memories of a bank clerk, an artist, two French nuns and a priest who suffered torture and death. "They were terrible years and for me, also years of enormous stress: transporting people in secret through roadblocks" to escape.

"I too could have been among the outcasts of today, so that one question is always lodged in my heart. Why them and not me?"

— Pope Francis

Downplaying any personal heroism, he remarks on "the many shadows [that] hung over the Church itself" — deeply split between collaborationists and people seeking justice. As pope, he ordered the Vatican archives to open its diplomatic files in the dirty war years. Francis' revelations, in his voice, advance a powerful story leading to a broader terrain of human rights.

"More than sixty countries in the world treat homosexuals and transsexuals as criminals, a dozen or so with the death penalty, which is sometimes even carried out," he writes. "But homosexuality is not a crime, it is a human fact, and the Church and Christians cannot remain indifferent in the face of this criminal injustice, nor can they respond faintheartedly. They are not 'children of a lesser god': God the father loves them with the same unconditional love."

Francis paradoxically opposes "gender theory that seeks to cancel differences on the pretext of making everyone equal," a critique based on natural law by which Christian Nationalism has declared war on trans people like those Francis has pastorally welcomed as pope.

Pope Francis celebrates Mass at Ndolo airport in Kinshasa, Congo, Feb. 1, 2023. According to Congolese authorities, over 1 million people attended the Mass. (CNS/Paul Haring)

In one of the most powerful episodes, he visits war-torn Congo "with over 5 million deaths since the end of the 1990s. It is the largest conflict since World War II … with the scandalous indifference of multinational companies and foreign powers, ethnic forces fight to the death over natural resources and power."

"At Kinshasa I kiss the stumps of hands and feet that have been chopped off. I stroke heads. Listen to sighs … Their tears are my tears, their pain is my pain. And altogether we say: Enough! Enough of the atrocities that cast shame on the whole of humanity! It is time to stop regarding Africa as a mine to be exploited and a land to be pillaged."

Echoing his Laudato Si' encyclical on the climate crisis, he denounces an "economy that kills, that excludes, that starves, that concentrates enormous wealth in a few to the detriment of many, that multiplies poverty and grinds down salaries, that pollutes, that produces war."

"Everything is connected: a perverse system of meaningless development, deforestation that proceeds illogically and illegally and makes us lose an area of prime forest the size of Belgium each year, the destruction of entire ecosystems, the attack on biodiversity."

"When the Gospel truly exists — not a display of it, not an exploitation of it, but its concrete presence — there is always revolution."

— Pope Francis

Francis gives the strongest words imaginable by a world leader on the climate crisis. Hope is a book that should be taught in every class on political science, business and theology. Francis raises a challenge to all believers of the common good:

"When the Gospel truly exists — not a display of it, not an exploitation of it, but its concrete presence — there is always revolution. A revolution in tenderness … using your ears to hear the other, to hear the cry of the young, of the poor, of those who fear the future; to listen to the silent cry of our common home, of the sick and contaminated earth. And after seeing, after listening, there is no saying. There is doing."