President Ronald Reagan gives a press conference in the Old Executive Office Building in Washington, D.C., June 16, 1981. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

A mystifying irony of the moment is that amid the greatest threat to the republic since the Civil War, and as Trumpian conspiracy theories reach levels that in any other era would be dismissed as preposterous nonsense, there is a corresponding gush of truth-telling.

The latter runs from the daily newsletters of historian Heather Cox Richardson, to the pile of books on Donald Trump as an unprecedented threat, to the ongoing excavation of the effects of slavery and segregation. Deep academic treatments warn of the rise of authoritarianism in the United States, and insiders explain how and why evangelicals have made an idol of Trump. One of the most compelling political offerings is Oath and Honor: A Memoir and a Warning, the courageous documentation by former GOP Rep. Liz Cheney of the elaborate plan of Trump's mob and complicit members of Congress to overthrow a presidential election.

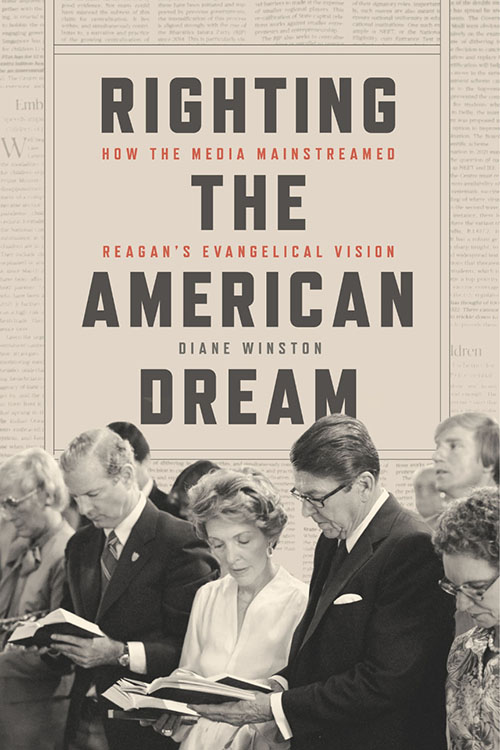

Into that mix arrives an unsettling examination of an era and a president too often held aloft as an example of Republican sobriety and statecraft, and depicted as an offset to today's reality. Righting the American Dream: How the Media Mainstreamed Reagan's Evangelical Vision by Diane Winston is a measured, serious and meticulously detailed account of the interactions of the Reagan era and its significance for today. Winston, a distinguished journalist and scholar, is Knight Chair in Media and Religion at the University of Southern California.

In many ways, Reagan was the origin story for today's Republican Party and a model for those inclined to demean government and the media.

The manufactured versions of reality today are a time-warp distance from the reality-adjusting narratives that Ronald Reagan, as Winston details, so convincingly conveyed during his tenure in the 1980s. There exists, however, a progenerative connection between then and now, even if what Reagan ultimately begat is, to be fair, far more sinister and destructive than anything he might have imagined.

Whatever the case — or era — Winston's research also holds a warning for the dangers that inhere even for the most conscientious journalists past and present. Simply recording and conveying the narrative of one side or another can make one complicit, however unwittingly, in advancing fanciful narratives or just plain falsehood. Report Reagan's version of events during the invasion of Grenada, when media was excluded, and that becomes the story no matter how much correction follows.

Report — as responsible media feel obliged to do — Trump's promise of bloodbath, his ambitions to dictatorship, his language about immigrants, the press, the justice system or his claim that there are "good people" on both sides, and they become, for some, the truth. It matters not how much backpedaling he does or how much evidence is then compiled to demonstrate that none of it is true.

Such a realization raises the stakes on journalism's ongoing struggle to achieve objectivity — or, more realistically, to understand what objective tools work in service of the craft. It raises the stakes as well on the more difficult challenge of how to deal with easily demonstrated blatant falsehoods that are also widely accepted as truth.

Ronald Reagan gives his acceptance speech as presidential nominee at the Republican National Convention in Detroit on July 17, 1980. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

Reagan's 'religious imaginary'

Essential to Reagan's influence on culture and politics was what Winston intriguingly describes as Reagan's "religious imaginary," a device that combined his awareness of the value of religious language with a political vision that included "the magic of the marketplace" and individual responsibility as cure-alls for whatever ails society.

Reagan's religious imaginary, she writes, was based on John Winthrop's "A Model of Christian Charity," a 17th-century treatise believed directed at fellow Pilgrims in the Massachusetts Bay Colony that fell into obscurity only to be rediscovered 300 years later and appropriated as "a social contract rooted in God's love for America."

"A religious imaginary expresses a commonsensical, collective understanding of what matters and why," Winston writes. "It accomplishes this by integrating metaphysical truths, ethical norms, and civic virtues into the core convictions and salient images defining a good citizen and a good society." In effect, it becomes a country's "lived religion."

Reagan's religious imaginary was nothing new. His "core convictions echoed the same worldview that religious conservatives had held for decades," Winston notes. "But when he became president, his faith in this religious imaginary had a significant impact on the nation. Invoking his worldview in speeches and interviews, it was normalized through subsequent news narratives." He embellished Winthrop's metaphor of a "city on a hill," adding "shining" to the description.

Advertisement

Reagan has long been granted a pass in the popular imagination as a grinning, genial presence who gave Americans something to be happy about following the Iran hostage crisis and energy shortage traumas of the Carter administration. But there were considerably darker sides to his tenure in the White House.

One concerns multiple levels of scandal not treated in the book. Another, the main theme of this work, deals with his use of religious and economic language that gave the culture permission to draw conclusions and approve policies based on racial stereotypes, unfettered capitalism and a nationalistic arrogance.

"Reagan's ability to set and dominate news media narratives was crucial to his success," writes Winston. Two elements crucial to that dominance was his convincing inclusion of "religious or moral" elements in whatever the subject, and the media's dutiful reporting of whatever form his religious imaginary took at the moment.

Further, some in his administration knew how to exploit his experience as an actor and former GE pitchman. "Every moment of every public appearance was scheduled, every word was scripted, every place Reagan was expected to stand was chalked with toe marks," said Donald Regan, his secretary of the treasury and later chief of staff.

President Ronald Reagan addresses the nation on events in Lebanon and Grenada, speaking from the Oval Office in the White House in Washington, D.C., Oct. 27, 1983. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

The Reagan administration's expertise at controlling the media was on full display in his handling of the invasion of Grenada, which Winston analyzes in detail. Reagan controlled the narrative, conjuring up an exaggerated threat, and kept the press at bay for days. It was another sunny achievement for the U.S., a turn-the-page military event that, post-Vietnam, allowed him to declare that we'd won one.

The press responsibly reported Reagan's version of things, which became the first impression of the invasion. When journalists began to dig into and report the truth of the matter, it was too late. The country was happy and celebratory, and Reagan's polling numbers jumped.

Those polls "indicated that the public did not want to hear about the administration's exaggerations or outright fabrications," writes Winston. "Many Americans felt positive about the troops' success, and Washington's version of things prevailed."

Converging forces

A convergence of forces and actors — figures who constructed an American religiosity — undergirded Reagan's political ambitions. Televangelist preachers such as Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson; activists like Richard Viguerie, Paul Weyrich and Edward McAteer; and resurgent evangelical, Pentecostal and fundamentalist movements all played a role in reinforcing the religious imaginary.

President Ronald Reagan meets with Jerry Falwell at the Oval Office in the White House in Washington, D.C., March 15, 1983. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

The disparate groups that embraced the worldview that "linked God's blessing to individual responsibility agreed with the president on the importance of welfare reform, U.S. military dominance and traditional family values," Winston writes.

The emphasis on individual responsibility, another theme that was repeated in coverage of Reagan, elevated that narrative in the public imagination no matter how much reporters might frame stories emphasizing the administration's seeming insensitivity to poverty.

That attempt at balance, however, backfired. "Repeating Reagan's message — normalizing his ideas about the undeserving poor, indolent welfare mothers, and a Black underclass — softened public attitudes about fairness," writes Winston. "Reagan and his surrogates also played on deep-rooted currents of racism and sexism as well as newer fears of economic displacement and cultural marginalization that many whites harbored."

President Ronald Reagan shakes hands with Donald Trump at a reception for the Friends of Art and Preservation in Embassies Foundation, at the White House on Nov. 3, 1987. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

Reagan understood the real fears in the land and he knew how to exploit them.

In many ways, Reagan was the origin story for today's Republican Party and a model for those inclined to demean government and the media. It is a story that has run beyond the bounds of political decency and accountability. In today's toxic and splintered media environment, any reportorial attempts to explain it come up short.

Trump won the presidency eight years after Winston began research for the book. In an epilogue, which frankly serves as a kind of completing sector to a long arc, she doesn't settle on whether Trump is "either the apotheosis or the nadir of the Reagan religious imaginary." Why not both?

For those who use religion for political gain regardless of consequences, Trump is Reagan on steroids. For others, it might be difficult to imagine a more repulsive or sacrilegious religious imaginary than Trump's appropriation of the Bible, bedecked with a flag cover and bearing country lyrics and the words of the founding documents of a secular state, while referring to himself as a Jesus figure.

Righting America reveals the deep roots of the American religious imaginary, that dangerous mix of religion-fueled politics that has become the currency of those who would defile both religion and politics to hold onto power.