Sr. Jean Dolores Schmidt prays with the Loyola University Chicago men's basketball team in 2018. (CNS/Courtesy of Loyola University Chicago/Bill Behrns)

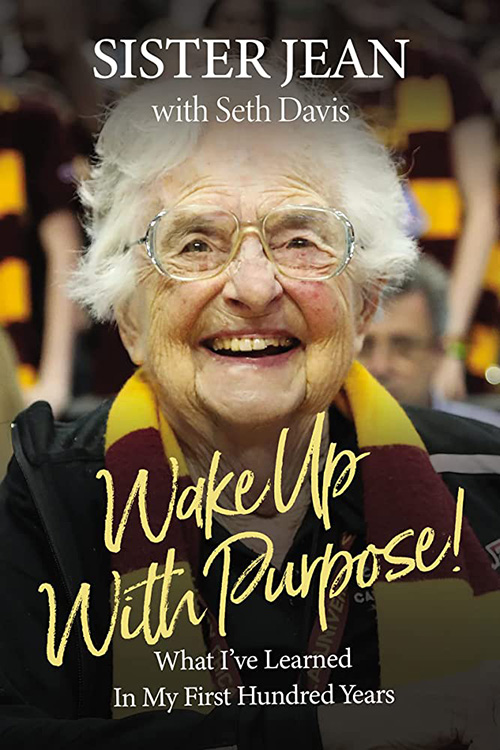

Sr. Jean Dolores Schmidt is a kicky, cool nun. But as she points out in her engaging new book, Wake Up With Purpose!, she prefers to be called "sister" because "nun" refers to women religious who are more contemplative and less engaged with the busy world.

No one could accuse Sister Jean of disengaging from the world. She's 103 years old and still active in various ways, including her now-famous role as chaplain of the Loyola University men's basketball team. When that team overcame the odds in 2018 by making it to the Final Four of the annual March Madness tournament, the world discovered — and, well, fell in love with — Sister Jean, who seemed to be featured in the media more than the team itself.

Now, with the help of sports journalist Seth Davis, she has written a delightful and lively memoir that tries to answer all the questions the media and the public raised about her a few years ago.

Advertisement

The Catholic Church can get no better press than this warm offering, made especially valuable because it covers her reactions to the many changes that have come for women religious in Jean's own long lifetime. In other words, the book is a living history of one corner of the church in the last 100-plus years. (For example, in one anecdote, family members couldn't find Jean in an airport because they were looking for her in a habit, which she no longer wore.)

The book also shows how a simple, even submissive, approach to theology sustained Jean when she didn't have an answer to the ancient question of theodicy: Why is there suffering and evil in the world if God is loving and all-powerful? A question that, so far, lacks a single answer that satisfies everyone.

The best that Sister Jean could do with that question is this: "We can trust that God has a reason for everything that happens, even if we don't quite understand it at the time." It is an approach to theology that often gets challenged, yet for Jean, it has felt sufficient decade after decade.

'Too often,' Sister Jean writes, 'we think of God as a very stern judge. I think in many ways, though, we're getting back to the spirit of acceptance in the church.'

Jean's centurylong journey, starting at her birth right after the end of World War I, takes us through much of American, world and church history. We also get the history of Jean's family and an account of her childhood years in her San Francisco home, in which she seemed to be a cheeky smaller version of the cut-to-the-chase adult she was to later become. Jean recalls how, if she thought guests in her parents' house "were overstaying their visit," she would "pipe up, 'It's time for you to go home now.' "

In many ways, the book paints Jean's mother to be her model for clarity and adaptability. You can almost hear the grin in Jean's voice when she notes, "Before my mom married, she used a horse and a motorcycle to get around. Yes, a motorcycle."

Jean's family was far from wealthy, though her parents managed to hold things together financially, even if it required getting rid of their phone in the Depression to save money. Her relative comfort with minimal financial assets seemed to make the decision to become a sister a bit easier.

Throughout the book, we find a woman deeply committed to her ministry but also unwilling to become a rigid ideologue: "Too often," she writes, "we think of God as a very stern judge. I think in many ways, though, we're getting back to the spirit of acceptance in the church."

Sr. Jean Dolores Schmidt holds a bobblehead made in her likeness while recuperating from hip surgery in January 2018. (CNS/Chicago Catholic/Karen Callaway)

She gives considerable evidence of having developed a progressive social conscience as she moved through her ministry, at one point noting, "In all my years at the three private Catholic schools where I taught in California, we did not have a single Black student. That is simply wrong and grossly unfair."

Like many priests and religious, Jean worries about their dwindling numbers. She says this of her community of the Sisters of the Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the motherhouse of which is in Dubuque, Iowa: "There used to be several thousand of us, but now we're down to a few hundred." Still, she invites young women to consider joining the BVM community.

Sister Jean's consistency in how she approaches the world, as evidenced in the book, is impressive. Even when she was inundated with interview and autograph requests as the Loyola basketball team was advancing through the NCAA tournament, she remained unimpressed with herself. When shown a drawing for a proposed bobblehead doll of her image, it wasn't her looks or her clothing she had qualms with, but rather the fact that there was no basketball in sight. "What's that all about?" she recalls quipping. "So they fixed it by putting a ball in my hands."

Wake Up With Purpose! proves what many of us have long known: Sister Jean, humble, smiling, loving, funny and caring, has become an important face for the Catholic Church. The church couldn't make such a person up — and it should be grateful that it didn't have to.