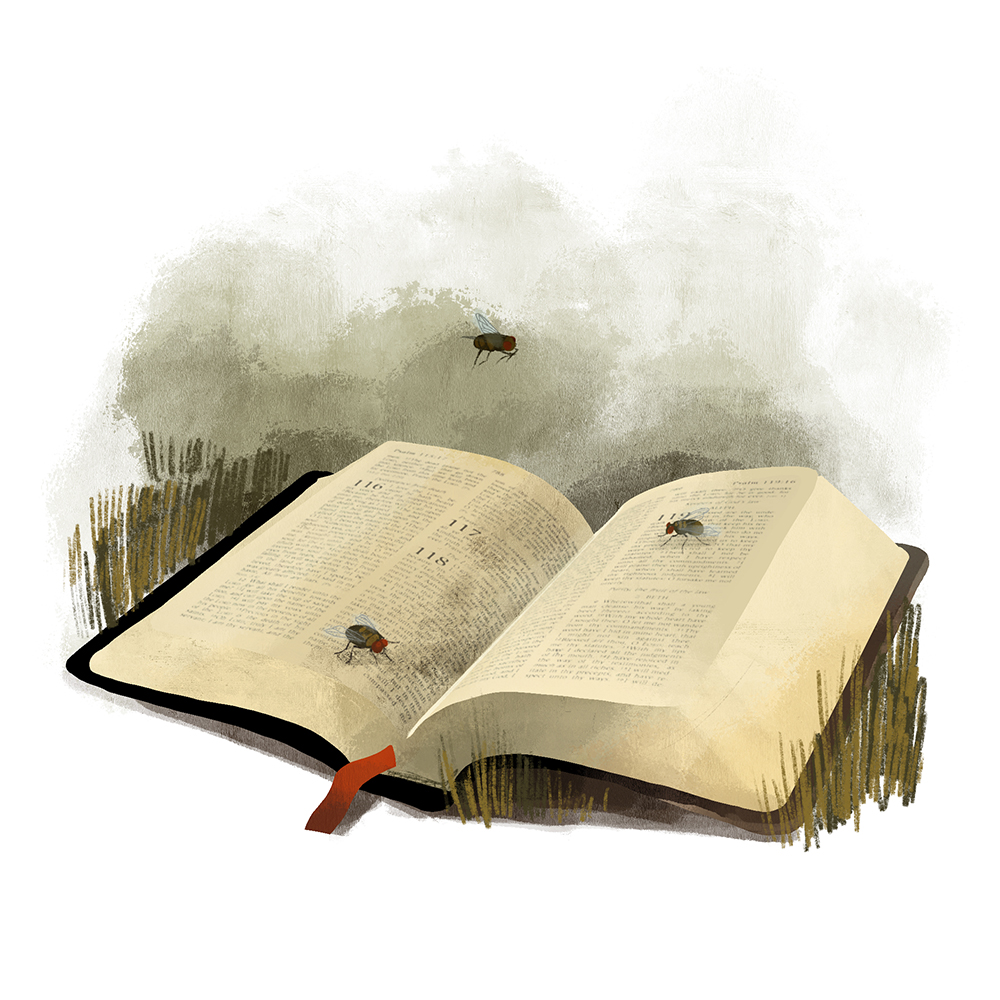

Ethel Cain's debut album, "Preacher’s Daughter," is a Southern Gothic exploration of religious trauma through the story of a fictional character. (Artwork by Ryan McQuade)

I don't know how to heal religious trauma. How do you begin to piece through decades of devotion? When the house of your belief is burned to the ground, the work of turning over the rubble, looking for valuables is tedious and painful. You might find treasures intact in the ash, but some things you felt were sacred have been caught in the fire and will never be what they once were. I turned to religion for an answer to my own pain, looking for a novena or a portrait of Our Lady that would heal the deep wounds inflicted by Christians, but while religion claims it can save you from anything it has a hard time saving you from itself.

I first heard about Hayden Anhedönia — better known by her alter ego, Ethel Cain – on TikTok from raving teens spellbound by the artist. They testified that her debut album, "Preacher's Daughter," was dark, gruesome and transcendent: the best thing they had heard all year. Upon first listen, I understood what had them hooked.

The album opens with the sound of a Southern preacher mid-sermon on "Family Tree (Intro)." It's enough to transport anyone with southern roots back to a dilapidated white chapel; the kind with a sign out front that reads "Hell is Real. Jesus Saves," a fan buzzing in the corner against the oppressive heat and old wooden pews that are hard and unforgiving. Ethel introduces herself with the lyric "These crosses all over my body/ Remind me of who I used to be." Before we even know Ethel we know her scars, etched by a collision of faith and inner turmoil.

Cain's thoughts on humanity are rather hopeless, reflecting "Jesus can always reject his Father/ But he can not escape his mother's blood/ He'll scream and try to wash it off of his fingers/ But he'll never escape what he's made up of." To Ethel Cain, humanity seems to be a curse; a curse that will play itself out over the course of her life.

"Preacher's Daughter" goes on to tell that story and the horrors that await Ethel Cain. It is a Southern Gothic gem, an unapologetically raw and brutal nightmare.

(Ryan McQuade)

Anhedönia herself is not unscathed by religion. Growing up on the Florida panhandle, she learned to sing in the choir of the Southern Baptist church with her mother where her father was a deacon. Hayden left the church at 16 after coming out as gay and later a transgender woman. She described her departure and the haunting presence of a religious upbringing to the "Artist Decoded" podcast: "When I moved out, I was like, 'Oh, I'm free, 'I'm out of the church, out of the South, I'm gone, I'm a free woman, a free bird,' " she said. "But then it started to creep up and I was like, 'Oh there's a lot wrong here.' And I realized that the aftershock, the lingering effects of Christianity, were not going to be easily dealt with and forgotten."

For Hayden Anhedönia healing these "aftershocks" took the form of Ethel Cain. She explains, "So [Ethel Cain] can just be a pair of shoes that I put on and go on stage and I'm the embodiment of like anger and religious trauma and these crazy horrific things and then I take it off and I'm a normal person and I'm healing and I'm getting better."

Advertisement

There's something cathartic about listening to "Preacher's Daughter." You’re welcome to step into the shoes of Ethel Cain as long as you can stomach it; to move around in the depravity of the human condition and the brutality we can inflict on others and ourselves in the name of God. It's an experience you don't find often in church. There are sacraments for the penitent, retreats for the lost, but where are the services for those who need to scream at the top of their lungs? Where can you confess that the trauma has turned to dreams; dreams of burning down a church or smashing a statue or running away or cursing the Divine? Where do the blasphemers go on Sunday?

The fictional Ethel Cain, after years of abuse by her preacher father, runs away. Her buried trauma takes the form of men: men she will fall in love with, men who will abuse her and a man who will ultimately kill and cannibalize her. If that last point has made you sick to the point of clicking away, then we've gotten to the point of this album.

Trauma, while it may be religious, is not purely spiritual. It manifests in the sinking gut, sweating palms and nauseous memories. I will not presume that this album is for everyone. "Preacher's Daughter" is for the traumatized; those who need an outlet to feel the anger that comes from being abused, ostracized, vilified or shamed by an institution emboldened with divine authority. The album is a visceral ride, but refreshing in its honesty.

"Preacher's Daughter" is for the traumatized; those who need an outlet to feel the anger that comes from being abused, ostracized, vilified or shamed by an institution emboldened with divine authority.

"Preacher's Daughter" ends with our protagonist in heaven but her gospel is not one of unification with God. Rather she sings in "Sun Bleached Flies," "God loves you, but not enough to save you/ So baby girl good luck taking care of yourself." In the end, her love is for her mother, who stays up late worried about what has become of her missing daughter. "Mama, just know that I love you/ And I'll see you when you get here."

I don't know how to heal religious trauma. But I know that it starts by feeling it. It means something for someone else out there to echo the doubt and anger and sincere desire I still have to exist in a community that cradled me in one arm and hurt me with the other. I'm not certain that the church will ever become that "safe place" but I'm happy to have found it in this album. I hope it inspires more artists to channel their trauma into art, characters and worlds, no matter how macabre they may be.