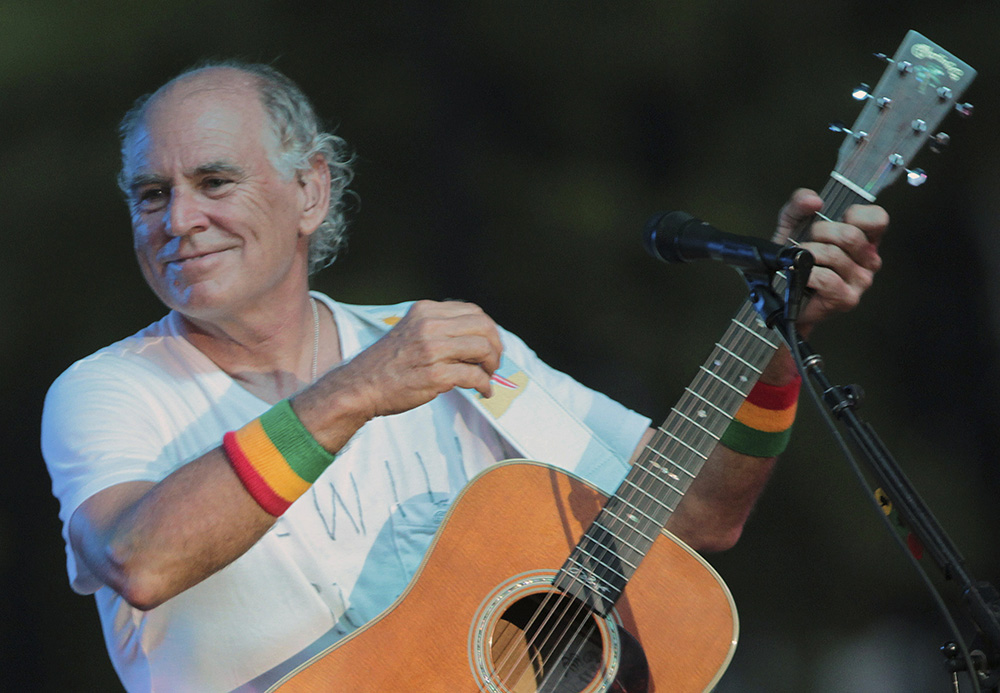

Jimmy Buffett performs at his sister's restaurant in Gulf Shores, Alabama, on June 30, 2010. (AP/Dave Martin, File)

In the wake of celebrity death, people become inherently curious about the person beyond their most public contributions — and one of the most pressing questions becomes their faith. Were they religious? Did they believe in an afterlife? Essentially, what did they think was going to happen to them when this moment arrived?

Last weekend, that conversation began anew as music fans across genres mourned the death of famed beach-bum bard Jimmy Buffett. It felt almost too providential that Buffett — who made it feel like summer all year round — passed on to eternal life on Labor Day weekend, heralded in the United States as the official end of summer.

It played at something deeper in all of us than just the death of a fun-time-generating musician, which led to the bigger questions. Why do so many resonate with the music of Jimmy Buffett — and is there something deeper at play in his songs?

Many outlets were fascinated to find that Buffett was raised Roman Catholic in the South. (Although astute listeners would have heard him say, "I was supposed to have been a Jesuit priest" in "We Are the People Our Parents Warned Us About," and wouldn't be that surprised!) Is that surprise correlated to a feeling that Buffett's brand — a lifestyle of board shorts, frozen cocktails, and toes in the sand — could not connect with a sense of the divine?

Perhaps there is more to the story than a pair of sunglasses and sandy toes defining Buffett's mentality. Was the world Buffett's music crafted akin to the kingdom of God?

Advertisement

The truth is, many people find that type of bliss-seeking escapism to be incredibly spiritual. (And certainly, this author finds being by the water to be profoundly sacramental!) Buffett's presentation was of serenity as a spiritual pursuit, through simple avenues: a boat at sea; a lost shaker of salt; or a ground beef patty layered with lettuce, tomato and Heinz ketchup.

In our capitalist society and experience of adulthood, driven by how much we can produce and the glorification of busyness, Buffett's music challenges us to slow down, to set aside productivity in exchange for rest and renewal, and to see the beauty in the seemingly ordinary. His storytelling crafted a universe in which that slower pace becomes like a retreat, where turning off the noise and intensity of life allows for the voice of peace to be heard.

That certainly resonated with the millions of "Parrotheads," fans of Buffett who congregated for a rollicking concert experience or even just savored the cool taste of Landshark Lager while listening to "Volcano" by the barbecue. Buffett's ease and peace of spirit cultivated a sense of community in anyone seeking the pleasure of eternal summer.

The community is intergenerational: Buffett has been making popular music since the 1970s, and so at least three generations of listeners can connect in the spirit of the "good times" his music evokes. Few things can bring that many generations together with a smile!

Listeners can find Buffett drawing us even deeper beyond relationship with one another, into relationship with something bigger and broader. He invited listeners to be aware of the world around them, respectful of nature and the presence of God alike.

Was the world Jimmy Buffett's music crafted akin to the kingdom of God?

Specifically and acutely, you can hear him sing about the sacramental nature of the ocean and feeling a connection to the divine in "Saltwater Gospel," his collaboration with the Eli Young Band.

"Coastal Confessions" includes a one-sided account of Buffett, a self-proclaimed "altar boy just coverin' his ass," irreverently returning to the confessional after decades, but he uses the adage to paint a relatable picture of a man who journeyed through a life rife with mistakes and is looking for the wisdom in the mess.

Less intensely identified might be a sense of spirituality and soulful tranquility that ran through other Buffett hits. Arguably his most famous hit, "Margaritaville," challenges the conscience to accountability (through the avenue of a blender rendering a frozen concoction).

"Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes" is practically Ignatian in its detachment to adjust "if it suddenly ended tomorrow" and consistently pointing to laughter in the spiritual life.

"Breathe In, Breathe Out, Move On" reminds the listener to set aside stressors and worries, not allowing grudges to steal our proverbial oxygen. Might there be remnants of "turn the other cheek" from another famous seaside teacher and preacher?

In the end, none of us can speak to Jimmy Buffett's spiritual state at the end of his life. We can only see the spirituality that ran through his music and the world he tried to create: one with less noise and stress, more peace and attentiveness; less hurt and grudges, more celebration and sunsets; and at least the occasional cheeseburger in paradise.