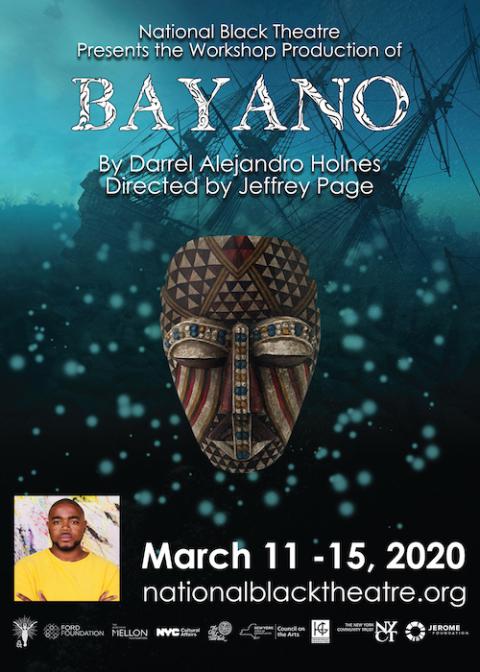

Darrel Alejandro Holnes, a playwright who grew up in Panama, presents workshop productions of his latest play, "Bayano," at the National Black Theatre in New York City, March 11-15, 2020. (Thomas Kuhn)

The empty rehearsal room was quiet in late afternoon, a peaceful contrast to the hustle and bustle of buses, cars and people visible through the windows looking out on 125th Street, one of Harlem's busiest thoroughfares. Darrel Alejandro Holnes came here to talk about his latest play, "Bayano," which two weeks later, starting March 11, is having its first public exposure in a workshop production upstairs at the National Black Theatre.

It's been a two-year journey to get to this point, from first applying to National Black Theatre's I AM SOUL Playwrights Residency program, through acceptance and writing and rewriting the play. Using "The Odyssey" as inspiration, Holnes wanted to tell the story of Bayano, a 16th-century enslaved African king who led the largest slave rebellion in Panama against the colonial Spanish.

"He was the Harriet Tubman figure of Panama," Holnes said. "He was the greatest colonial liberator anywhere in Latin America."

Promotional artwork for "Bayano" (Provided)

Throughout the creation of "Bayano," as he has with his other work and his life, Holnes has been strengthened by his Catholic upbringing in Panama and the African spirituality that mingled with it. He wears a silver cross containing sand from Jerusalem, a gift from his mother, over his cream-colored sweater, an outward sign of his faith. This faith is needed now more than ever, he said, when he has trouble finding anything hopeful in the news.

"Faith is ultimately where I find my optimism," he said. "It's helped me move forward through this process despite many setbacks."

Born in Houston, Holnes was raised in a suburb seven minutes outside of Panama City. He returned to the United States in 2005 at age 17 to attend Loyola University in New Orleans but never completed the first semester because Hurricane Katrina left the school underwater. He transferred to the University of Houston, then went on to the University of Michigan for graduate school.

It was his grandmother, "the spiritual center of our family," who influenced his faith formation. She moved to Panama from Costa Rica in the early 20th century.

"The church gave her pride, place and a sense of community," he said. "So much of her life was shaped by her commitment of faith."

But Holnes is also aware of the church's role in protecting the institution of slavery in Panama. Portraying this history, along with creating a theatrical drama of song, dance and story around Bayano's life was important. Holnes had first learned about Bayano in elementary school, but mostly it was in relationship to news of rebellions and slave escapes. He wanted to explore the history, spirituality and liberation of this historical figure.

"The story was well documented but never from his perspective or a black perspective," Holnes said. "I've done my best to try to honor what his perspective was and give him a voice. It's the story of a great liberator and also tells the story of the struggle with faith."

And he's worked to understand both sides of the church in colonial Panama.

"The church's role in faith helped Africans get up in the morning, but religion was also used to explain and use slavery," he said.

In addition to a solid body of work and awards, Holnes also has the distinction of being the first Panamanian American to receive a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship — in 2019 for his poetry — and he is one of only two artists of Panamanian descent to ever receive the honor. In addition to writing, he teaches at New York University and at Medgar Evers College at the City University of New York.*

"In a lot of my plays, the characters are always struggling with their faith," he said. "To believe is to ask questions. My characters are always asking questions about life and its responsibilities."

While he still sees Catholicism "as part of my community" and worships at Sagrado Corazón de Jesús (Sacred Heart of Jesus) Catholic church* when he is in Panama, he now attends Middle Collegiate Church on Manhattan's Lower East Side because its practices of service are much closer to those he experienced as a child.

Advertisement

"I grew up with a community of Catholic churches that were incredibly active in social justice. I grew up thinking that being Catholic is volunteering in a soup kitchen," he said. "I felt the Catholic Church was to be a voice of the poor and needy. I feel the Catholic Church in the United States has a different dynamic. Middle Church is very activist-oriented and really lives by faith."

Throughout the 45-minute interview, Holnes holds a hand-carved wooden staff with the head of an African man that he bought in Cuba.

"It makes me feel close to this project. I think what it would be like to be someone enslaved. They take everything from you so you own nothing. You would want something of your own so you go out and make it."

After the play's workshop presentation March 11-15, Holnes will work toward getting the show into a fully staged production, which he hopes will make people feel empowered.

"What I admire about Bayano is that he really took his freedom into his own hands," he said. "We should be able to do even more. We can break from things that oppress us. I hope people will try hard to feel they can free themselves from anything they feel is holding them back."

*Editor's note: This article has been updated to clarify the college name at CUNY and to correct the name of the parish in Panama.

[Retta Blaney is an eight-time award-winning journalist and author of Working on the Inside: The Spiritual Life Through the Eyes of Actors.]