"The Virgin and Child with Saints Dominic and Aurea, and Patriarchs and Prophets" by Duccio di Buoninsegna, ca. 1312-15 (Michael Centore)

At the entrance to "Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350," an exhibition at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art on view through Jan. 25, hangs a small Byzantine icon of the Virgin and Child from the 13th century. On an adjacent wall is a painting of the same subject by the Sienese artist Duccio di Buoninsegna.

Though the two works were executed only 30 years apart, one can already detect in Duccio's piece the stirrings of a new artistic style. Freed from the precision of the Byzantine line, Mary's drapery falls in billows and folds, and the infant Christ emerges from the flatness of perspective into a livelier, more naturalistic pose.

Advertisement

Duccio is one of four main Sienese artists featured in the exhibition, which surveys a golden age of painting that prefigured the humanism of the Renaissance in the following century. Curators have assembled over 100 works in a variety of media to tell the story of this brief but epochal moment in the history of Western art.

It is in the "Maestà," an altarpiece painted for the Siena cathedral in 1311, where we encounter the full scope of Duccio's vision. The double-sided work originally featured an image of the Enthroned Madonna on the front and 40 scenes of the life of Christ on the reverse. The exhibit has gathered several of these panels for the first time in centuries, offering viewers the rare opportunity to view them together.

"The Calling of the Apostles Peter and Andrew" by Duccio di Buoninsegna, from the back predella of Maestà Altarpiece at Siena Cathedral, ca. 1308-11 (Michael Centore)

Each of the eight panels from the "predella," or altar shelf, on display from the rear of the "Maestà," is a window onto the gospel. The jewel-like scenes shimmer in their interplay of color, pattern and passages of gold, like icons where the artist's personality is allowed, ever so discreetly, to shine through.

In a panel depicting the calling of Peter and Andrew, Christ stands on a rocky shore, gesturing to the two apostles in their boat. Peter pivots to Christ with one hand raised as if in acceptance of the invitation, while Andrew's half-turned body and pensive expression betray a certain hesitancy. Duccio has painted the water beneath them with undulating strokes of translucent blue, a rhythm reflected in the movement of fish that swim against the waves.

In the decades following the "Maestà," Sienese artists took up the form of the polyptych, a multipaneled assemblage that allowed for creative and compositional flexibility. One room of the exhibition is dominated by Pietro Lorenzetti's altarpiece for the church of the Pieve in Arezzo, a polyptych that rises on three tiers of panels capped with pointed arches.

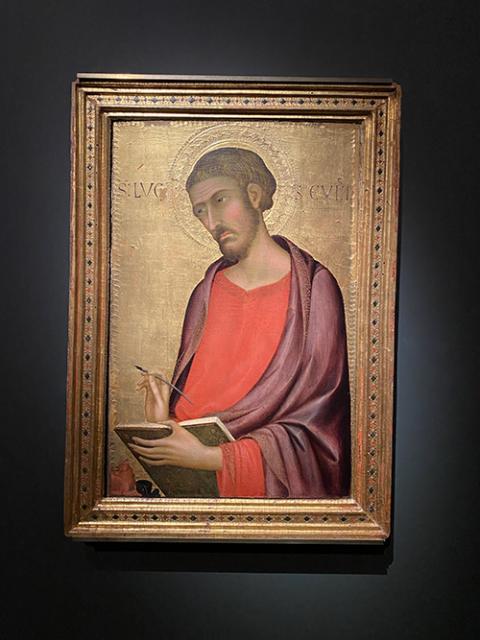

"Saint Luke" by Simone Martini, from the Palazzo Pubblico Altarpiece, ca. 1326-30 (Michael Centore)

With only five panels, Simone Martini's polyptych for the altar of Siena's Palazzo Pubblico is much smaller than Lorenzetti's, though I found in its intimacy an experience of prayer that connected me to its original purpose. A panel of St. Luke drew me in with its portrayal of writerly inspiration. We catch the saint in mid-thought, pen poised above an open book, eyes averted as if in search of the next word to add to his gospel.

Siena's location on the Via Francigena, a trading route that linked northern Europe to Rome and the more distant lands of the East, made it a crossroads of cultural influences. Sienese artists incorporated Gothic, Byzantine and Roman styles, as well as motifs drawn from Asian art. In its spirit of openness and assimilation, Siena rivaled Florence as a center of creative activity.

Nowhere is this more evident than in a section of the exhibition devoted to textiles. Sienese merchants traded fabrics from the Mongol territories of Eurasia, including China and Iran. The curators have brilliantly paired several of these swatches with reproductions of paintings where their patterns reappear, such as the lacelike leaves of a delicate silk weaving repurposed by Martini and Lippo Memmi in their "Annunciation with Saints Ansanus and Massima." Seeing this was a reminder of how human culture evolves in dialogue, and the ways in which art can overcome boundaries of distance, language and time to create a new synthesis.

"The Entombment" by Simone Martini, from the Orsini Polyptych, ca. 1335-40 (Michael Centore)

The remaining galleries feature work by Pietro Lorenzetti and his brother Ambrogio, as well as sculptures and objects of private devotion. One of these, Martini's "Orsini Polyptych," is a stunning series of panels small enough for transport.

In a panel depicting the entombment of Christ, figures tumble along a descending line from the left, bewailing the loss of their Master. Mary leans over the body of her son and lifts his head to touch her cheek. Behind her, the Beloved Disciple takes Christ's hand in his and presses it to his lips.

The image is striking in its saturated color and bold use of pictorial space, but even more so in its emotional compression. Martini has rendered a whole inventory of grief with remarkable economy. Like Duccio's painting of the Virgin and Child, it reveals a humanity that will shift people's perception of religious art — and with it, their understanding of themselves.