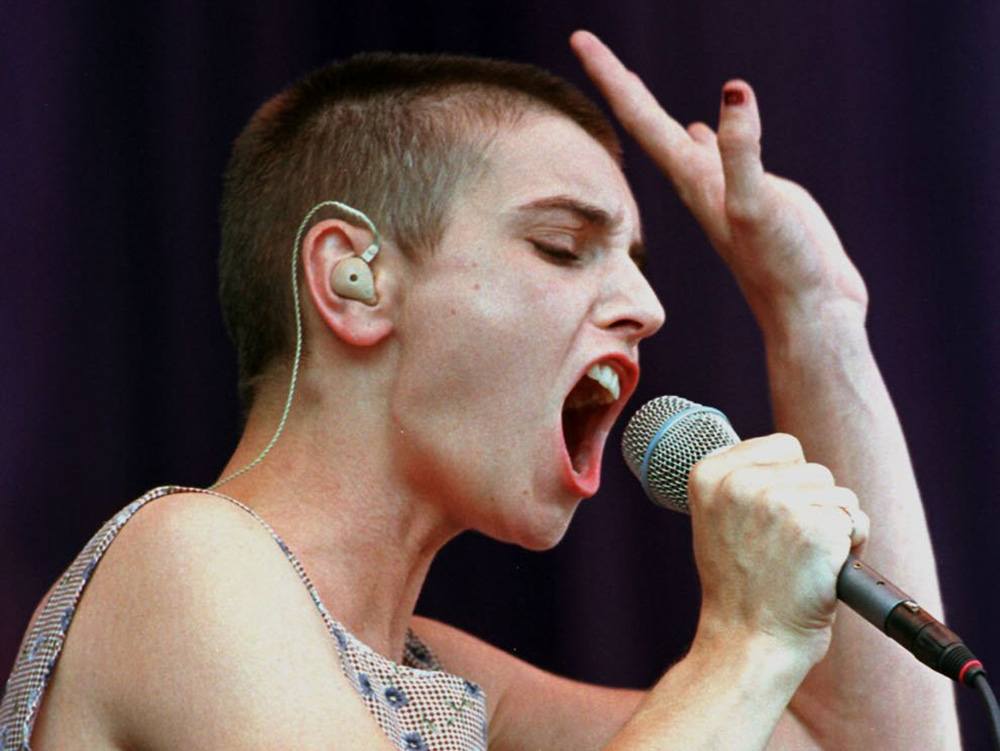

Sinéad O'Connor performs in concert in Pasadena, California, in 1998. (CNS/Reuters)

In 2010, when Pope Benedict XVI issued a pastoral letter apologizing for hundreds of years of sex abuse by clergy in Ireland, he also failed to offer any suggestion that the church's policy toward abusive clergy would change. This did not sit well with Sinéad O'Connor, whose career had been permanently damaged 18 years earlier when she tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II on "Saturday Night Live."

In an opinion essay for The Washington Post in response to Benedict's letter, she was blunt. Irish Catholics, she wrote, "are in a dysfunctional relationship with an abusive organization."

Today, when many Catholics around the world feel the same way, we can more easily understand that in her willingness to sacrifice her career for the sake of the truth, she was prophetic. But like so many other women throughout history, she suffered greatly for it. For Gen X women in particular, however, and Gen X women who grew up Catholic even more so, she represented us in a way no other celebrities did.

Sinéad's prophecy prepared us for the earthquake, if we were willing to listen.

Gen X Catholics were in their 20s and 30s when the Boston abuse scandal broke, and we became the first generation to disaffiliate from religion at the same rate that Millennials and Gen Z later would. But we also watched as Sinéad, our peer, sporting a shaved head like Joan of Arc, tore up that photo of the pope years before The Boston Globe's Spotlight investigation led to Cardinal Bernard Law's disgrace and the thousands upon thousands of revelations of global clergy abuse that would follow. Sinéad's prophecy prepared us for the earthquake, if we were willing to listen.

I didn't own a television in 1992, when Sinéad stood in front of a field of burning candles on Saturday Night Live and tore a photo of the pope, because someone had broken into my apartment and stolen the TV. I was 21, and learned about her performance a few days later, at my Catholic college. Shortly after my graduation, the college president, a male member of a religious order, would be removed for having a sexual relationship with an 18-year-old male student.

I recall some of my professors mumbling condemnations of Sinéad. That photo had belonged to her mother, who had violently abused her before convincing Sinéad's father to send her to a Magdalene laundry, Ireland's homes for "wayward women."

Advertisement

For two years, teenage Sinéad listened to other Catholic girls crying and screaming as the nuns on staff told them they were "terrible people."

Generations of women in Ireland have stories like this, and shocking news like the discovery of 800 infant corpses in the septic tank of a Magdalene Laundry in Galway are a horrific reminder of the scale of abuse Irish Catholics endured. Scientists and psychologists are just now beginning to unpack the mysteries of epigenetic trauma, and to understand that violence and abuse can damage not only their immediate victims, but generations of people who came afterward.

The abuse crisis broke the Catholic Church in Ireland. Irish Catholics, sick of their bodies being policed, would later vote overwhelmingly to legalize same-sex marriage and abortion. At his installation in 2022, the new bishop of Galway, Michael Duignan, said that the church in Ireland "is crumbling before our eyes."

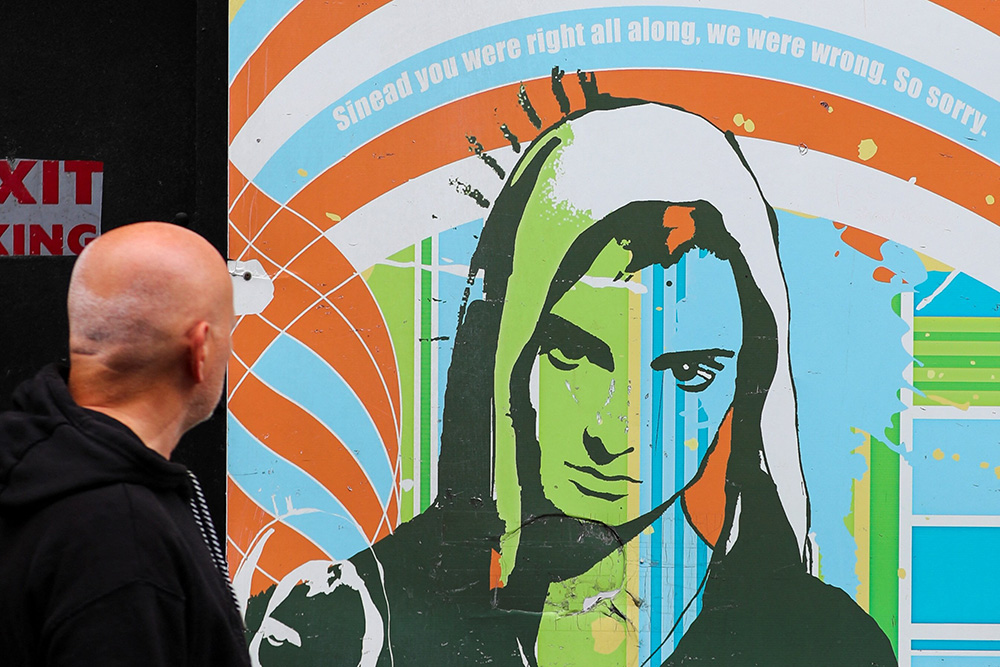

A man looks at an artwork depicting Irish singer Sinéad O'Connor in Dublin July 27. The July 26 death of the acclaimed 56-year-old singer and songwriter has seen an outpouring of tributes from all walks of Irish life. (OSV News/Reuters/Damien Storan)

And as parishes close and dioceses declare bankruptcy in record numbers, American Catholicism is seeing the rot of clergy abuse crumble its own foundations as well.

Like so many other Irish Catholics of her generation, however, Sinéad tried to hold on to things about Catholicism she saw as worthy of saving. In a conversation with Washington Post readers about her op-ed on Benedict, she wrote that "we Irish have always adored the Holy Spirit," and that the Holy Spirit might be the one to clear the church of "bad leaders."

She added, "Let me make [it] very clear that I am not a hater of Catholicism. And I believe the name of Catholicism can be made good again by changing its present leaders and by confession and transparency."

Sinead O'Connor is seen with a tattoo reading "Lumen Christi" in 2015. (MTI via AP/Balazs Mohai)

Sinéad would later get ordained in a breakaway Catholic church before eventually finding peace as a Muslim. In her 2021 memoir, Rememberings, she wrote that "the Koran is like a song" and God is "an incredible songwriter."

This kind of spiritual restlessness is not entirely unfamiliar to her Gen X peers. With only half of Gen Xers describing religion as "very important" to our lives, we have felt more liberated than previous generations to change religion, explore alternative spiritual paths, or leave religion behind altogether.

In pictures taken for a New York Times profile of her in 2021, O'Connor, who changed her name to Shuhada Saquat but still answered to Sinéad, wore a hijab along with a Star of David ring and a large hand tattoo that read "Lumen Christi." In Islam, she explained to a reader who complained about the clash of symbolism, "the Q'ran exists to confirm all previous scripture. So one can keep one's Star of David rings and Christian tattoos."

As Gen Xers stumble into midlife, we do so knowing many of our own musical prophets have died. Kurt Cobain, Tupac Shakur, Chris Cornell and too many others whose music also blended rebellion, spirituality and social critique are gone. To add Shuhada/Sinéad to that list is a grief, and a special kind of grief to a Gen X Irish American Catholic woman like myself who needed her example so badly in order to stop being a good girl and start speaking truth to power.

In her case, by the time people were finally ready to listen, the world's cruelty had run her down, and it was too late. In the wake of the loss of her extraordinary voice with her death on July 26, I hope we can better listen to other wounded women, calling out for justice in our broken world.