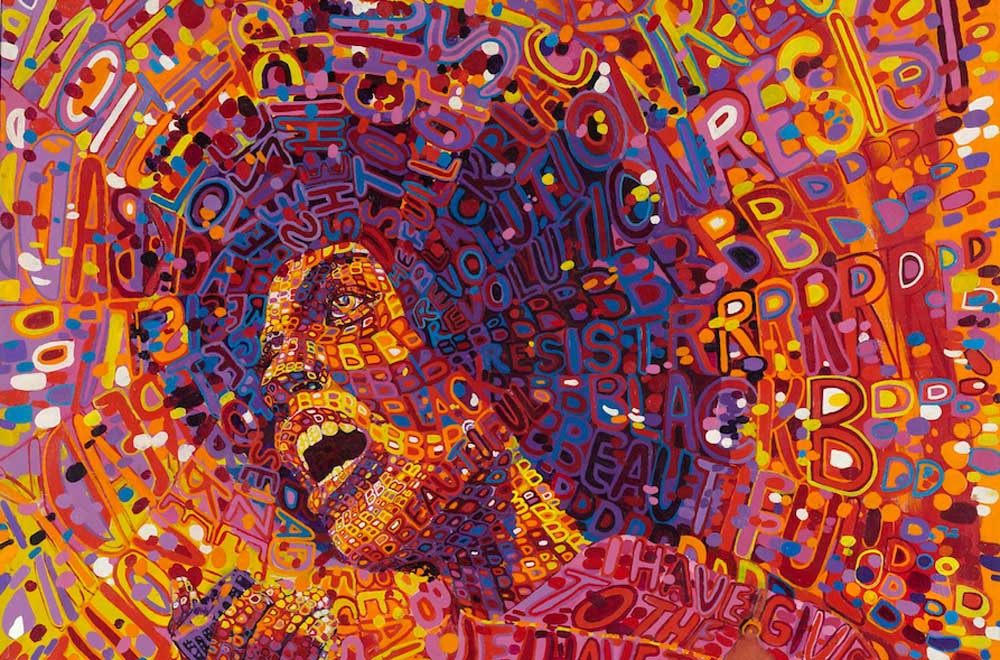

"Revolutionary (Angela Davis)" by Wadsworth Jarrell, 1971. © Wadsworth A. Jarrell. (Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum)

The Brooklyn Museum has done it again. Even with a number of splendid exhibitions in New York this season — the grandeur of "Delacroix" at the Met, the revelation of Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim, major retrospectives of Andy Warhol and Bruce Nauman at the Whitney and the Modern, respectively — the essential one is "Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power."

After originating at the Tate Modern in London (curated there by Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley), it has come to the Brooklyn Museum until Feb. 3, where it is curated by Ashley James. For knock-out art, historical depth and current timeliness, it can't be beat.

Including over 150 works by more than 60 artists, the show covers the tumultuous years of national change from 1963 to 1983. The background spans the years of protests against the Vietnam War, the height of the Cold War, the space race and moon landing, second-wave feminism, Watergate and the erosion of trust in a wide range of institutions. The foreground is the response of black artists asserting themselves with striking diversity in painting, sculpture, photography, prints and assemblages.

The first half of the show, on the museum's fifth floor, is organized geographically and begins in New York, where a group of 15 painters led by Charles Alston, Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis in the summer of 1963 formed the Spiral Group, intending first to organize a bus trip to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. (The group included one woman, Emma Amos, who at 25 was also the youngest.)

They held one group show in Greenwich Village in 1965, with the single requirement that all works include social comment exclusively in black and white. The restriction was not difficult for the fairly established Bearden, whose large-format photomontages were winning wide recognition. Yet it was a risk for Lewis, who had won acceptance, if not wide exhibition, among the abstract expressionists. But see his stunning "Processional (aka Procession)" (1965), based on images from the Selma to Montgomery march, and the earlier "America the Beautiful" (1960), which gradually reveals itself as a fearsome gathering of the Ku Klux Klan.

"Processional (aka Procession)," by Norman Lewis, 1965, from a private collection; © Estate of Norman W. Lewis (Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, New York)

Nearby is a mini-show in a single gallery showing the photography of New York's Kamoinge Workshop (Kamoinge being the Kikuyu word for "a group of people working together"). Leading the group was Roy DeCarava, whose restricted, velvety range of dark tones gave his work contemplative depth and sometimes also, as in his famous "Mississippi Freedom Rider, Washington, D. C., 1963," monumental presence.

Despite the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the violent events of the years from 1965 (with the assassination of Malcolm X and the Selma March a month later) to 1968 (and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination) heightened the sense of need for black artists to support black causes. In 1966, Stokely Carmichael made his famous call for "Black Power." The artist-educator David Driskell set about organizing a major exhibition on the history of black artists. (The eventual result was the landmark "Two Centuries of Black American Art, 1750-1950," in 1976, first at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and then at the Brooklyn.) The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition was founded in 1969, and new institutions like the Studio Museum (1968) and El Museo del Barrio (1969) sprang up in Harlem and East Harlem.

The gallery recalling this scene — in New York especially — is centered on Elizabeth Catlett's gleaming Mahogany sculpture "Black Unity" (1968), with a raised fist on one side and portraits of a black man and woman on the other. Directly behind it is Faith Ringgold's "The Flag Is Bleeding" (1967), from her "super-realist" American People Series. In Benny Andrews' "Did the Bear Sit Under a Tree?" (1969), fist and flag figure together as a man with a zipper for a mouth shakes his fist at a flag made from rolled-up fabric. Another all but heartbreaking painting is nearby, Archibald Motley's "The First One Hundred Years: He Amongst You Who is Without Sin Shall Cast the First Stone: Forgive Them Father For They Know Not What They Do." The medley of dark images includes the crucifixion, Ku Klux Klan crosses, Satan and the dove of peace side by side, and more; the artist worked on the painting for nine years, and then never painted again.

An installation at "Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power," running Sept. 14, 2018 through Feb. 3, 2019, at the Brooklyn Museum in New York; from left: "Did the Bear Sit Under a Tree?" by Benny Andrews, "Black Unity" by Elizabeth Catlett, and "The Flag Is Bleeding" by Faith Ringgold (Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum/Jonathan Dorado)

Continuing its geographical survey, the Brooklyn show moves to Los Angeles, shaken by the Watts Rebellion in 1965, where artists like Melvin Edwards, Betye Saar and John Outterbridge worked especially in assemblage, celebrating the potential of found materials while also deriving from the practical need to "make do with what one has." Then a smaller gallery, centered on the Bay Area, recalls the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense that Bobby Seale and Huey Newton founded in 1966 and to which Emory Douglas's bold, aggressive poster work in the movement's newspaper The Black Panther brought an urgent immediacy that still startles.

The final, and largest, gallery on the fifth floor has show-stopping art from Chicago, where Organization of Black American Culture started on the South Side in 1967 and became famous especially for its "Wall of Respect," a mural celebrating African-American heroes and heroines. A year later, African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists, or AfriCOBRA, was formed and sought to contribute even more directly to liberation causes. Among its leaders was Jae Jarrell, two of whose radical fashions are shown in front of three large portraits by her husband Wadsworth Jarrell in typically "coolade colors": Malcolm X as "Black Prince," Angela Davis wearing his wife's "Revolutionary Suit" (complete with cartridge belt) in "Revolutionary (Angela Davis)," and "Liberation Soldiers." (The portraits, done in acrylic with a liberated pointillism, suggest Gustav Klimt on psychedelics.) But there are other compelling artists here as well, mostly figurative — Jeff Donaldson, Gerald Williams, Barbara Jones-Hogu — though with one punchy, pure abstraction (James Phillips' "Aggression").

An installation at "Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power," running Sept. 14, 2018, through Feb. 3, 2019, at the Brooklyn Museum; from left: "Revolutionary (Angela Davis)" by Wadsworth Jarrell, "Revolutionary Suit" by Jae Jarrell, and "Liberation Soldiers" by Wadsworth Jarrell (Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum/Jonathan Dorado)

Downstairs on the fourth floor, aesthetic exploration rather than geography is the organizing principle. And it starts with an absolutely gorgeous piece by Sam Gilliam, "Carousel Change" from 1970, an enormous piece of canvas painted lyrically in multiple acrylic hues and hung so that it seems to be held aloft by multiple tent poles. Forget that it blurs the distinction between painting and sculpture. You just want to dance under it.

Thereafter the art is for the most part so arresting that you may overlook the tension between figuration ("Show the real lives of our brothers and sisters!") and abstraction ("Why limit it to the Man?"). So we have Jack Whitten's "Homage to Martin" (1970), a fierce, frontal black triangle (a set of triangles within one another, actually), whose surface the artist has roughened with his Afro comb. And Frank Bowling's expansive abstract landscapes in acrylic that faintly reveal stencils of continents formerly laid beneath them. And William T. Williams' homage to John Coltrane, "Trane" (1969), a terrific, slashing spectrum of diagonal bands of color intersecting and overlaying each other and loosely organized around an irregular rectangle angled at 45 degrees in the center of the painting.

Sam Gilliam, "Carousel Change," by Sam Gilliam, 1970, from Tate Museum, courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, California; © Sam Gilliam (Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum/Mark Blower)

There is also all manner of figurative work. "Three Graphic Artists," at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1968, featured the revered Charles White and his students David Hammons and Timothy Washington. Barkley Hendricks became known for his life-size portraits — "Blood (Donald Formey)" from 1975 is a prime example — but also for provocative, and revealing, self-portraits. The show also includes a searching, warm portrait by the white Alice Neel of her black friend Faith Ringgold (1977).

Other artists were "rethinking the surface," as curator James puts it, with Ed Clark using a broom to spread the blocks of color on his abstractions, Martin Puryear refining the finish of wood sculptures like "Self" (1978) so that you want to caress them, and Alma Thomas becoming enamored of space travel and painting "Mars Dust" (1972). Still others worked to bring movement into their pieces: Joe Overstreet producing brilliantly painted, tent-like objects such as "We Came from There to Get Here" (1970); Melvin Edwards hanging a "Curtain (For William and Peter)" (1969), made of barbed wire and chain; and David Hammons tossing high on the wall "Bag Lady in Flight" (1975), made of shopping bags, grease and hair.

The show concludes with a section on Linda Goode Bryant's Just Above Midtown Gallery in New York, which made space for experimental black art for 10 years between 1976 and 1986. Here the stand-out is the collection of photographs of "Art Is…", a 1983 performance piece by Lorraine O'Grady. Dressed as her alter ego Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, O'Grady led a float up Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard with performers carrying empty gold frames that onlookers could pose in — and become themselves art.

"I think art's goal," O'Grady said, "is to remind us that we are human, whatever that is. I suppose the politics in my art could be to remind us that we are all human."

Advertisement

In what is now a second age of Black Power, the fecundity of the artists in "Soul of a Nation," not to mention their courage and commitment, is both bracing and beautiful. How effective were the alarms they rang about the depth of racism in America? Surely there have been gains in the equality of African-American citizens in the three-plus decades since — the emergence of black corporate leaders, the national (if not universal) recognition of King as a major moral prophet, the election of the first black president of the country, the opening of the great National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington, and most recently the stirring campaigns of two black politicians for the governorships of two Southern states.

But the recent police violence against black men that has resulted in the Black Lives Matter movement, not to mention the ingrained segregation of major cities such as Chicago, Detroit and Baltimore, make the use of the language of progress and equal justice seem not simply evasive but offensive to many. While filming his summer hit, "BlacKkKlansman," a reality-based film on 1970s racism, Spike Lee did not have to look far to find a contemporary coda in newsreel footage of last year's "Unite the Right" white supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia, about which our sitting president said there were very fine people on both sides.

Where, you have to ask, are our political parties, civil society and religious communities seriously doing enough to address the fissures in the fabric of the nation?

But in the art world at least, there are signs of awakening. The Met Breuer this fall showed the sculpture of Jack Whitten. There is an acclaimed exhibition of Charles White at the Museum of Modern Art. And the Smart Museum of Art on the South Side of Chicago is showing "The Time Is Now! Art Worlds of Chicago's South Side, 1960-1980," featuring many of the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists who appear also in "Soul of a Nation."

Whose "soul"? Whose "nation"? For many of the artists in "Soul of a Nation," it was their own souls they sought — and longed to save. For many of them, "nation" meant a nation of equality and freedom — for themselves, their sisters and brothers so long deprived of that dignity.

The essential question now is how to cultivate such a community, or at least a community of communities — open, in equality and freedom, to all, with dignity and opportunity for all. It is not merely, I think, a matter of "inclusion," or even "integration." Reconciliation and rebirth would be better words.

Indeed, the time is now.

[Jesuit Fr. Leo O'Donovan is president emeritus of Georgetown University in Washington and a frequent commentator on the arts for NCR.]