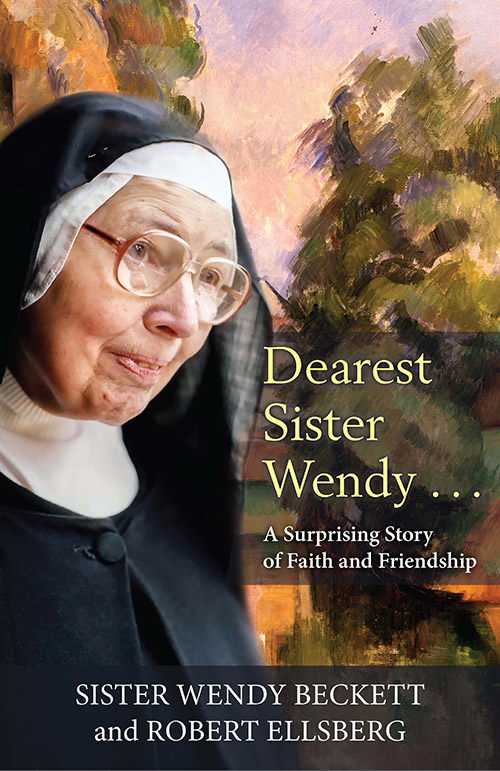

Sr. Wendy Beckett and Orbis Books publisher Robert Ellsberg exchanged letters on a near daily basis during the last three years of Sister Wendy’s life. Initially, the two corresponded about the lives of saints, the meaning of holiness and the spiritual life, but they soon delved into a deep and intimate exchange that encompassed the subjects of love, suffering, joy and the presence of grace in everyday life. (Courtesy of Robert Ellsberg)

Many people, as I did, first came to know Sr. Wendy Beckett in the 1990s through her popular television program, "Sister Wendy's Odyssey." She was an unlikely celebrity: diminutive, dressed in a medieval-looking black habit of her own design, her lively and intelligent features offset by large spectacles. Yet countless viewers became entranced by her tour of famous galleries around the world, and by her incisive and empathetic commentary on the works of art she encountered along the way.

What made this public life all the more remarkable was that since 1970 she had lived as a consecrated virgin and hermit in a caravan on the grounds of the Quidenham Carmelite monastery in Norwich, England. She had embraced that life, a modern version of the anchorhold of her hero, Julian of Norwich, after receiving a dispensation to leave Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, the teaching order she had joined at the age of 16.

Arguably, traveling around the world with her own television show was a departure from the spirit of her solitary vocation. But she accepted it, while it lasted, as a kind of ministry: an opportunity, as she put it, to talk about God to people who were perhaps uncomfortable with religious language. For Sister Wendy, all beauty pointed to the source of Beauty. And through art, she hoped to teach people in the modern, secular world how to see reality in its inner depth. When this ministry faded, she happily returned to her solitary life of prayer.

I had come to know Sister Wendy through publishing U.S. editions of four of her books, and she had generously endorsed several of my own books about saints. Yet I would not have considered her a "friend." Sister Wendy avoided extended correspondence, and her own inscrutable handwriting served as an effective deterrence. And yet, in the last three years of her life I was witness and partner to something remarkable, a deep friendship that indelibly changed both our lives.

By this time, for reasons of failing health, Sister Wendy had moved from her caravan to a cell within the monastery cloister, where she was visited once a day by a sister who brought her food, wheeled her to Mass in an alcove above the chapel, and helped her with correspondence by taking dictation. It was this that facilitated our unexpected correspondence. Sister Wendy, as she revealed to me, was suffering from terminal heart and lung ailments. Whether this contributed to her willingness to share herself as never before, I cannot say. But in what started as an exchange of friendly emails, we quickly found ourselves in an almost daily correspondence that lasted until her death in December 2018.

Wearing my publisher's hat, I encouraged her to write more about her own story and inner life. She rejected this idea as rubbish; she considered herself as of no interest or importance. Yet at some point, as our exchanges ventured into deeper and more personal matters, she suggested that perhaps the book I was describing was hidden all along in our correspondence. Prompted in part by reflections on God's presence in my own life — a story marked by heartache and failures as well as by extraordinary signs of grace — she gradually opened up in return.

She had always disdained self-examination, yet she began to share stories of her own childhood, her early intimations of the sacred, her sense of being an odd misfit in most of her surroundings, her misplaced assumption that in becoming a nun in a teaching order she would be able to pursue her calling to a life of prayer, and how, in seeking to follow God's will in all things, she had found her path to a life that most perfectly suited her temperament and her calling. And yet, remarkably, it seemed that in opening our hearts to one another in this way Sister Wendy was embarking on a new and unfamiliar odyssey.

Through my eyes on the world, and my encounters with authors and friends whose faith was expressed in work for peace and justice, she said that I was opening new horizons in her solitary cell. And through her commentary and loving response to my personal life — including the stories of my childhood, the influence of my father, Daniel Ellsberg (the famous whistleblower and peacemaker), my work in writing about saints, my own trivial ailments, my letters to Pope Francis, and even my dramatic dream-life — it was if she took it all in, placed it on the altar of her heart, and returned it with her blessing.

All this while, Sister Wendy was suffering from painful heart attacks, and a stiffening of her lungs that made breathing an ordeal. I was moved to consider that all these hundreds of long letters were literally dictated with her failing breath. And yet she evidently found not only pleasure but purpose in our exchanges. Occasionally she would share her own deeply symbolic dreams, which shed their own light on the meaning of her contemplative vocation, and its intersection with the world of art.

Advertisement

At the end of our second year of correspondence in 2017, I was thrilled to be invited to give a retreat for the sisters at Quidenham. Sister Wendy noted that we would only have a brief opportunity to meet, since she would not attend the retreat, and she repeatedly tried to curb my expectations with warnings about her deafness and "general dullness." I greatly enjoyed the opportunity to share with the sisters many of the themes that had emerged in our correspondence — particularly Pope Francis' notion of a "journey faith" in which we meet God along the way, a way marked by times of doubt and uncertainty, as well as illumination. But the highlight for me and my fiancée, Monica, was to meet Sister Wendy face to face. It was hardly necessary, since, as she had said, we had already met one another "heart to heart." Her parting words were: "You know, for me, this is heaven."

That theme was dear to Sister Wendy. With her favorite Carmelite saint, Elizabeth of the Trinity, she believed that we carry heaven within us — God's presence in our soul. The spiritual life was a matter of awakening to this reality — a reality that was not dimmed by pain or suffering. She had intuited this herself, even as a child, and it was her wish to impart this knowledge to others.

Sister Wendy's last message to me was in a letter shared with other friends. "I know you will be sad but I hope also very happy for me that I am close to death." She was moving out of the monastery to a care home. "When the day comes I want you to turn to God with great thankfulness for all He has given me. This is the time of the deepest joy." In a typical postscript she added, "How embarrassing it will be and depressing if the Lord works a miracle and I don't die after all!"

After her death on Dec. 26, 2018, I spent many weeks reading through our voluminous correspondence, encouraged by Sister Wendy's intuition that there was a larger purpose and message to be shared. The result was finally a book, Dearest Sister Wendy ...: A Surprising Story of Faith and Friendship. My hope is that those who read these letters will discover the person behind the television persona: a modern mystic, a genius of the spiritual life, a person of far-seeing sensitivities, a great lover of God whose capacity for love she was still discovering at the end of her life. And perhaps they will feel included in her final apostolate of friendship.

Editor's note: This article previously appeared in the Oct. 8 issue of The Tablet in the U.K. and is reprinted with permission.