(Dreamstime/Yuri Arcurs/Scalinger)

Editor's note: This story has been supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

Mary Rittle says she experiences climate anxiety every single day. It may be a 55-degree January day in Chicago, when she notices that birds that should have migrated are still around. Or it could be after reading about how melting polar ice caps are endangering people around the world. Even her environmental activism can trigger anxiety because it reminds her of the urgent need for such work.

"This overwhelming sense of worry and fear and helplessness is very easy to get caught up in," says Rittle, who is a freshman at Loyola University Chicago. "I sometimes feel like, what could I possibly do? Why is no one taking this seriously? Why are lawmakers and corporations not taking this seriously?"

But Rittle's activism also helps relieve her anxiety, as does spending time in nature. Another anxiety-buster is having a community of like-minded students at Loyola University Chicago, where she is active in the Restoration Club and a new group, called "Eco-Warriors."

Eco-Warriors was founded last year specifically to address climate anxiety among students, especially those in the School of Environmental Sustainability. Jesuit Br. Mark Mackey heard students in his eco-spirituality course talk about feeling overwhelmed, not being able to get out of bed or deciding against having children because of their fears about the climate crisis.

So he gathered some students together for weekly meetings. "It helps just hearing that you're not alone in these worries and having a place to vent and get out your frustrations," Mackey told EarthBeat.

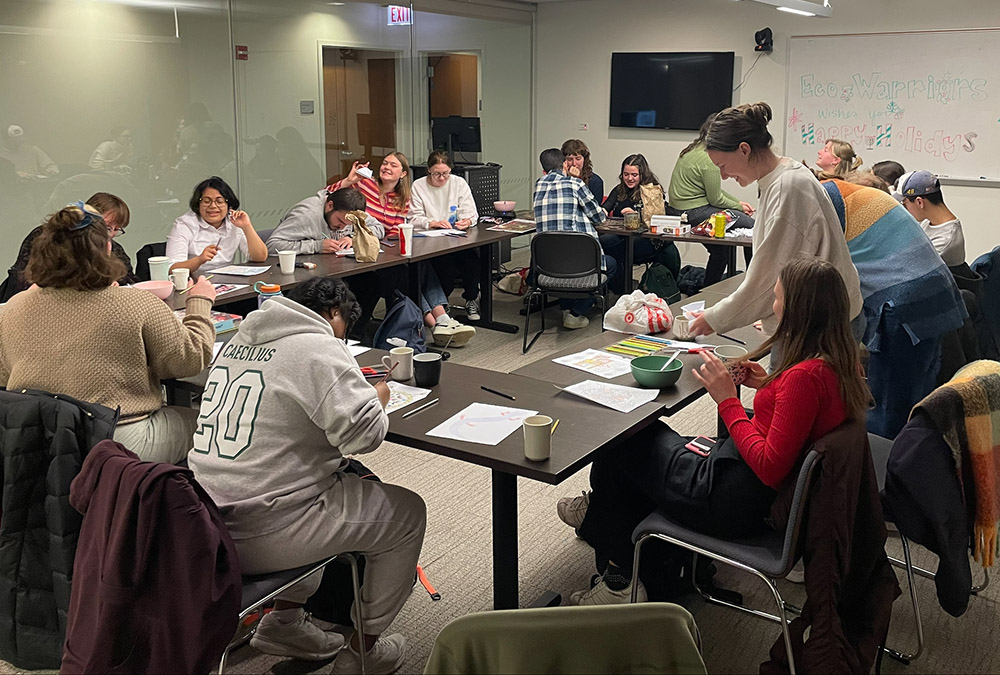

Now in its second year, the group's success is evident from student interest. It has attracted nearly 30 people and would likely appeal to more, but Mackey does not advertise in an effort to maintain the small-group feel.

At the group's first meeting, Mackey wrote "Eco-Worriers" on the board, only to have a student change "Worriers" to "Warriors." It has become a ritual that begins each meeting, and underlines how action can transform anxiety.

Climate anxiety — sometimes referred to as "eco-anxiety" or "ecological distress" — goes beyond concern for the environmental peril facing the planet because of global warming. It manifests itself much like other anxieties, with intrusive thoughts, sleeplessness, a racing heart or shortness of breath, and interference with relationships, work or school. It can include a range of feelings, from helplessness and sadness, to hopelessness and despair.

Experts say that distress is a normal human response to a crisis. But for young people, climate anxiety can be compounded by social media and other stressors.

The "Eco-Warriors" group meets at Loyola University Chicago. (Courtesy of Mark Mackey)

While young people are resilient, their anxiety around climate issues can be subtle, and those who work with them — teachers, school counselors, campus ministers — should be educated and attuned to it, say those involved in programs to address climate anxiety. The antidotes, they say, include environmental activism, community support and spiritual sustenance.

Young people who struggle with climate anxiety agree.

You are not alone

The poor air quality in Alexa Santana's lower-income neighborhood worries her, as does the fact that several family members have asthma. "I feel anxious for the state of our world," said the sophomore at Fontbonne Academy in Boston.

She is not alone. A 2021 survey of young people, ages 16-25, found that more than half (59%) were very or extremely worried about climate change, and 84% were at least moderately worried. Nearly half (45%) said their feelings about climate change negatively affected their daily life and functioning.

Fontbonne theology teacher Stephen Michael Tumolo sees climate anxiety as just another stressor on this generation. "It's part of the anxiety of simply being a young person in America today," he said.

Kayla Jacobs attends a climate march in Chicago in 2019. (Provided photo)

But the school's involvement in the Catholic Climate Covenant's Youth Mobilization Program has helped build community and given students a purpose in the climate movement — which has in turn relieved some of that anxiety.

The project's national program manager, Kayla Jacobs, says much of the anxiety she sees among high school students is extreme, something she would describe as closer to despair.

"It's not just nervousness, but really affects their decision-making and planning for the future," she said. She herself used to suffer from insomnia because of her fears about the environment.

One of the Youth Mobilization Program's goals is to turn anxiety into hope by community-building and action through regular meetings of a student leadership team and a yearly Catholic Youth Climate Summit, with workshops, speakers and action-planning. A recent summit in Boston was followed by a lobbying day at the Massachusetts State House, in which students were trained and matched for meetings with their local representatives to advocate for several green bills. A similar summit took place in Chicago in February.

In debriefs after the summits, students told Jacobs that before the program they felt scared and powerless. "By the end, they have built that community and feel that they know what the next steps are," Jacobs said.

Taking action, she said, motivates students to continue to work for change. "Whether it's a small win or a big win, at the school level or federal level, it keeps the momentum going."

Santana says her activism helped her connect with others who share her values — and her worries. "Advocating for climate change not only helps others learn more but it helps you connect with other people who are feeling the same way you do," she said. "If you find those people and connect with them, you can feel some relief and feel more heard."

Jacobs also believes in intergenerational support, and connects students with adult allies. She is encouraged that environmental issues are less political among younger generations, whether they identify as conservative or liberal.

"I definitely have hope with the future in their hands," she said. "My job is to make sure we have a future to put into their hands."

In fall 2019, students in an environmental studies class at Stone Ridge School of the Sacred Heart in Bethesda, Maryland, conduct a stream study in Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C. (CNS/Courtesy of Catholic Standard/Stone Ridge School of the Sacred Heart)

Sam King, director of integral ecology for the Marist Brothers, also believes participatory action is the best antidote to climate despair. Student "Green Teams" at Marist high schools across the country are attracting a growing number of students who are involved in projects such as building native plant sanctuaries and implementing circular plastic waste programs.

"When we feel that we're part of something bigger than ourselves, and when our spirituality nourishes our action, we feel a sense of hope," King said. "These are the moments we're trying to lift up and focus on."

Yet King also cautions against repressing all negative emotions and warns about the dangers of "toxic positivity." He tries to balance raising alarm and using positivity to bring people together.

"We need to honor the range of emotions that can arise from climate anxiety," he said. "There is a certain amount of alarm and dread that can be useful, and there is a place for righteous indignation and fear. We need to hold space for these emotions and not just gloss over them."

Spiritual sustenance

After doing grassroots ecological work in the Amazon for 11 years, Blair Nelsen went through a period of activism burnout. That's when she started hearing about climate anxiety and became interested in the inner work necessary for long-term movements for social change.

Blair Nelsen at a Sept 17, 2023, climate march joined by her son, Noah Prata Nelsen (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Now, as executive director of Waterspirit, which focuses on water issues and spiritually grounded environmental action, Nelsen thinks of herself as something of a "climate chaplain." One of her first projects after joining Waterspirit in 2019 was to start its Eco-Anxiety Support Group.

Waterspirit's program is based on the Good Grief Network's "10 Steps to Personal Resilience and Empowerment in a Chaotic Climate" method, which is in turn loosely based on Alcoholics Anonymous' 12 steps.

Although there are themes and resources as part of the 10-week support group, the real power comes from the conversations among the group members, Nelsen said.

"Deep listening and authentic, vulnerable sharing does a whole lot, especially when people are afraid of being seen as a 'Debbie Downer,' " she said. "Having space for that and knowing that your distress is a moral response to a society in crisis is incredibly affirming and resilience-building."

Participants from the 11 groups Waterspirit has hosted self-report in exit surveys that they see an overall improvement in their mood, and experience feelings of agency, resilience and empowerment. They also report feeling more connected and less alone, Nelsen said.

The small-group format of fewer than 15 participants, however, limits how many people can be reached, and the need for more mental health resources is urgent, Nelsen said. She also would like to see environmental advocacy organizations and spiritual leaders pay more attention to climate anxiety.

The space for Waterspirit's first Eco-Anxiety Support Group in 2019 (Courtesy of Waterspirit)

"I'm seeing an increasing openness to this, but there is still a lot of work left to do," she said.

Waterspirit was founded by a Sister of St. Joseph of Peace, but serves people of all beliefs. Similarly, programs at Catholics schools or sponsored by the Catholic Climate Covenant do not assume that participants are Catholic or practicing the faith.

Yet organizers say students are open and even hungry for spiritual resources to help what can be an existential anxiety, and that environmental spirituality and justice may be a point of connection with young people who are otherwise turned off by institutional religion.

Jacobs of the Catholic Climate Covenant said she has been surprised at young participants' openness, when other nonreligious options exist. "These students don't have to do a program with a Catholic lens on it," she said. "But we are offering something that they feel drawn to — that's the theological virtues of faith, hope and love in a very active type of way."

Advertisement

Yet young people are also very sensitive to hypocrisy and notice when church institutions don't practice what they preach, she added.

Tumolo of Fontbonne Academy teaches Laudato Si', Pope Francis' 2015 encyclical on the environment, and he sees students regularly quoting it in their writing assignments. "They know the pope's on their side, that he's pushing the system and trying to change things," Tumolo said.

King, of the U.S. Marist school network, believes that faith has much to offer those suffering from climate anxiety. "It can bring a sense of deep connectedness, belovedness and being held at a time of crisis," he said. "I think young people need that."

Faith can also nurture a sense of vocation as students discern their own role in addressing climate change. But those who work with youth have to be willing to meet them where they are, King said.

For many, their sense of "connectedness with the more-than-human world" comes through nature. "An eco-spirituality can be both a salve for the soul and a source of hope and catalyst for action," King said.

So much of climate anxiety touches on our human finitude, which traditionally has been the realm of religion, noted Mackey of Loyola's Eco-Warriors group.

Mackey tries to bring a Christian spirit of hope to his encounters with those suffering from climate anxiety, while still respecting students' own spiritual paths. "An encounter with God is an antidote like nothing else," he said.

Rittle, the Loyola freshman, also participated in the Catholic Climate Covenant's Youth Mobilization program in high school and presented on the topic of climate anxiety at last year's Ignatian Family Teach-in for Justice. She urges those experiencing anxiety to find connection.

"For anyone else who is struggling with climate anxiety, you are not alone," she said. "It's difficult, but there are so many of us working in our communities and in our own ways to help the situation. And I do believe things are going to change."