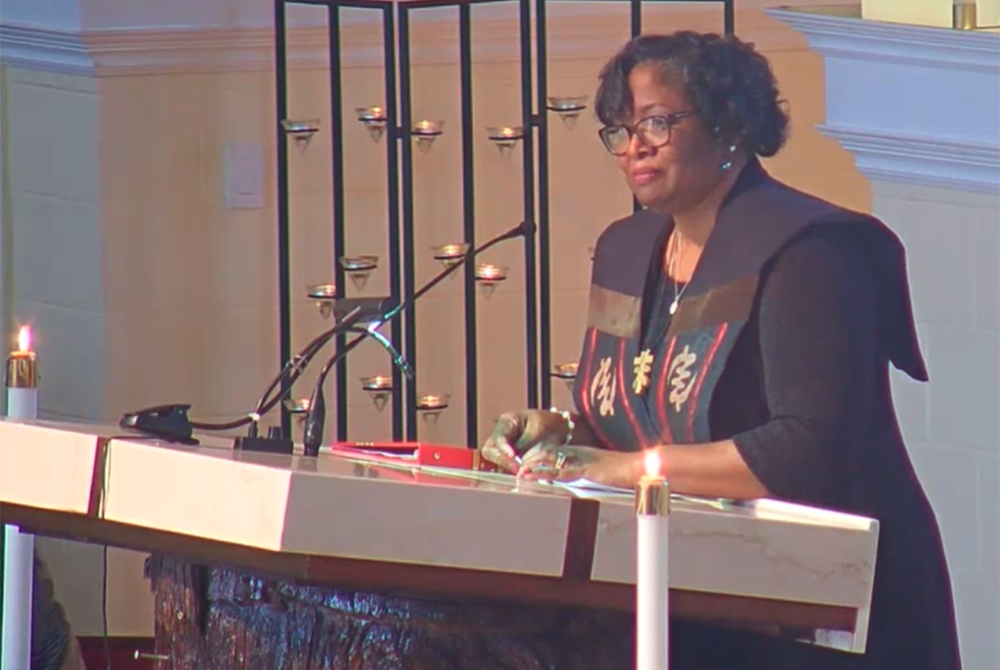

Sylvia Hood Washington speaks Feb. 12, 2017, at St. Columba Catholic Church in Oakland, California, in a screenshot via St. Columba's YouTube channel (NCR photo)

Sylvia Hood Washington wears a lot of hats. She's an environmental health scientist and engineer, as well as an environmental historian and author of Packing Them In: An Archeology of Environmental Racism in Chicago, 1865-1954.

In addition to serving on the EarthBeat advisory board, she's also a fierce advocate for environmental justice who sees climate change as inextricably linked to the sanctity of life, a view motivated both by her Catholic faith and her own life experiences.

During a July 16 interview with EarthBeat, Washington shared her story of suffering a miscarriage as the result of the 1995 Chicago heat wave, an event that led to 739 heat-related deaths in the area over the span of five days.

When asked, based on her experience and expertise, what she would say to bishops in the U.S. who don't yet consider climate change and environmental justice to be urgent issues, Washington said she'd ask those bishops to invite scientists like her into a room to have a conversation.

"The bishops need to understand that the science of climate change and the science of environmental pollution are sciences that deal with the integrity of human life. If you are pro-life, then you would want every human being to have that ability to be born as God's creation," Washington said.

Below are excerpts from EarthBeat's conversation with Washington, edited for length and clarity.

EarthBeat: I want to start with this: What do you think all Catholics need to understand about environmental justice and environmental racism?

Hood Washington: The thing all Catholics should understand about environmental justice and environmental racism is it's a right to life issue. Unequivocally.

Sylvia Hood Washington (Provided photo)

This is not about politics. This is about the sanctity of life from conception. And I emphasize conception because I am unabashedly pro-life. I believe that life begins at conception. By extension, and just as importantly, as we conceive life, especially human beings, at issue here is the disruption of human integrity during conception. So as an environment epidemiologist, I understand in our training research that life is actually degraded in the womb from exposures to chemicals.

[Some people] will say the environmental justice movement began in 1978. I will argue with anyone that environmental justice and the concept of environmental health degradation began with Lois Gibbs in Love Canal, where people were having disrupted pregnancies and the development of cancer.

So if you want the integrity of life as God intended us to be, [that means] not with damaged DNA, not with a reduction in lifespan and not with a reduction in life quality by being exposed to toxic waste.

Makielah Conway stacks up bottled water at her home in Flint, Michigan. "Whenever I use city water, I always pray," said the mother of three. (CNS/Tom Gennara, courtesy of FAITH magazine)

In recent years, the climate movement has brought the concepts of environmental justice and environmental racism more into the mainstream. This year, COVID-19 has brought more attention to existing health disparities between different racial groups. And in recent weeks, the country has been grappling with systemic racism and violence against people of color. As someone who has studied and worked on these issues for decades, what do you make of this moment?

I'm going to give you a specific example. Flint, Michigan, was in the news when Laudato Si' emerged. I am appointed by the governor of Illinois as an environmental justice commissioner for the state of Illinois, and I'm the Illinois EPA elected co-chair of the environmental justice advisory group. We know that lead exposures in the womb actually change the brain of children, creating learning disabilities. There used to be a statistic that something like some 30% of all incarcerated individuals had been exposed to lead.

These environments have been exposed to chemicals since the Industrial Revolution. As an environmental historian my research is based on this. When these African Americans and immigrants migrated out of rural agrarian society into rapidly industrialized urban environments, they were exposed to chemicals. Depending on how they were received in terms of race – and race is fluid; people who are Irish, Italian and Eastern European were not considered white – they were all pushed into industrial environments exposed to chemicals because there was no OSHA, there was no public health.

Protest about the Love Canal contamination by a resident, 1978. (Wikimedia Commons/Environmental Protection Agency)

These individuals have been left in these environments exposed to chemicals, and their immune systems have been degrading over generations. Then you lay on top of that exposure to chemicals like lead, now you have people changing mentally – not just psychologically, but their actual brains have been damaged by chemicals in the environment.

This is a powder keg and it didn't begin today. It's sad because the issues that we face today are the issues that we faced at the beginning of the 20th century. Agrarian communities moving and coming into factories, bodies being transformed, it lasted generations.

Of course, if African Americans, people of color and immigrants are moving into these urban spaces without any environmental protection and working jobs exposed to chemicals, we are in a toxic and volatile situation. That's why you see these protests. They already have a higher risk of developing COVID-19 and they come out and feel like they are being policed. They're overwhelmed by histories of cancer, histories of early death, and many times it's tied to environmental pollution.

You mentioned Laudato Si'. How do you think that ties into environmental racism and environmental justice?

I was flabbergasted when I read Laudato Si'. I love Pope Francis and I love the fact that he took all those researchers and scholars and brought that together because I have never read in my life as a historian and scientist someone who could weave a narrative about how we are changing all of God's creation. Laudato Si' is not just about solar panels. He is talking about the integrity of all life, and how the integrity of all life is compromised by our actions. If you cannot grasp the fact that what we do on an individual basis will have actual life changing consequences for those who are different from us, and those we perceive as less, then we have missed the boat in terms of our catechesis.

Advertisement

I understand that climate change has had an effect on your life. I was wondering if you'd be willing to share that story with us.

I live in Chicago but I'm originally from Ohio.

I'm blessed to have two live children. My third child would have been born in 1995, and that was the Chicago heat wave. We lost all of the [air conditioning] in our home. I went into stress. We got out of there. I had a very viable pregnancy, but because of the way I was born my body couldn't take the heat and I ended up having a miscarriage after six months. So, heat waves impact people's health and impact the lives of the unborn unfortunately.

At the U.S. bishops' conference fall assembly in 2019, then-president Cardinal Daniel DiNardo said during a press conference that climate change is not yet an "urgent" issue for the conference. From your perspective as someone who has studied this and someone who has been impacted, what would you say to bishops who don't consider climate change and environmental justice top priorities for the church in this country?

I would say, Please invite Catholic scholars like myself into a room and have a discussion. I think there has been, at least how environmental issues have been communicated in the media, a decoupling of the narrative from life issues. They'll talk about social equity. They'll talk about economic imparity. But the bishops need to understand that the science of climate change and the science of environmental pollution are sciences that deal with the integrity of human life. If you are pro-life, then you would want every human being to have that ability to be born as God's creation.

We do want to save babies. But I say that to you, that if you do not make climate change a priority, then that non-action will leave millions who are going to die and be compromised in the womb. We saw that with the Zika virus. It's going to cause deformities. It's going to cause spontaneous abortions. It's going to cause deaths from heat waves. And for those individuals living in urban environments with heat island effect: It's death. And by not addressing it, we are contributing or turning away from our fellow man dying.

Climate change is not about solar panels. I think that's great. But for me, as an epidemiologist and a Catholic, it's about saving lives from conception to natural death.

Union Camp Chemical Plant in Savannah, Georgia, 1973. (Wikimedia Commons/Environmental Protection Agency/Paul Conklin)

How can the environmental justice movement use the history you've mentioned and studied to continue moving the current conversation forward? Why is history valuable to the movement, and what initially drew you to become a historian?

My Ph.D. on the history of science, technology and the environment was sponsored by NASA. At the time I started my Ph.D., we were doing environmental policy and trying to look at how technology was changing lives after the 1987 Challenger disaster. At the time, NASA was starting to launch nuclear materials into space. And so we needed to go back and look at the history of our engineering and history of public health and medicine tied to nuclear waste. So, NASA would pay for my Ph.D. to understand the connection between public health and technology and science.

Now, in my book, this is the interesting thing, I found people of color and immigrants were always struggling with environmental health issues. Whether it was Eastern [European] immigrants in the back of the yards fighting off vector borne diseases from waste accumulating in the Chicago stockyards, or African Americans who were legally segregated were fighting with an epidemic of TB, which was actually an environmental disease. This is pre-civil rights movement. And what you see when you dig into the research is organizations working with churches, with other communities, to galvanize and change the actual living spaces, and therefore promoting life.

When the African Americans were doing this, they were coming into Chicago, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, around 1900-1918, and just working together across racial lines, across class lines to make their communities more sustainable.

We cannot despair. This is what history tells you: It doesn't matter who is in office as long you are guided by faith, you can reach across the aisles and you can see everyone as a full reflection of the face of God.

I understand the protests – that violence is real. But we need to come back and we need to bring everyone to the table to make our communities resilient regardless of who is in office.

Where can people go to learn more to keep this conversation going?

I think if people want to understand the history of people of color and immigrants from over 100 years ago and how they built resilient communities, they should check out my book Packing Them In: An Archeology of Environmental Racism in Chicago, 1865-1954. I am shocked at how relevant that book is today. Packing Them In is about the packing house industry and the unsafe environment before OSHA. Packing Them In is about individuals being pushed into unsustainable housing, and how that housing caused disease. The housing that we have now in these urban environments is going to contribute to COVID-19. But that book also talks about how these individual groups work in collaboration. That's an inspiring story. And I end in 1954, so we can go pre-civil rights and see collaboration in building sustainable communities.

Another book is my edited collection, Echoes from the Poisoned Well: Global Memories of Environmental Injustice. That's a great set of questions because it looks at communities all over the world and what they did to build sustainable communities.

If I step back at the church and look at it objectively, we are a global institution. We have one of the best individuals possible leading us in the Holy See. He has articulated the relationship between what we do individually and how it impacts the rest of the world. Our individual actions collectively have degraded the earth. Read Laudato Si'.

I'll give you one minute for any final thoughts.

People don't have to be activists. They don't have to be marching in the streets to create sustainable communities. Do one thing. People in Flint, Michigan, still are too afraid to drink the water. Your parish can organize a water donation for the children of Flint, Michigan. Your parish can organize a collection to bring fresh water to a family for one or two months. Whatever you can come up with, we can take action. When we see heat waves coming in, ask, "What can we do?" Have that conversation on a parish level.

[Jesse Remedios is an EarthBeat staff writer. His email is jremedios@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @JCRemedios.]