Collaborative Center for Justice staff and volunteers rally for climate justice at the Connecticut state capitol in 2019. (Courtesy of Dwayne David Paul)

Editor's note: EarthBeat is publishing a series of essays on the goals of the Laudato Si' Action Platform from speakers at the 2023 "Laudato Si' and the U.S. Catholic Church" conference, held virtually throughout June and July and co-sponsored by Creighton University and Catholic Climate Covenant. This essay is on the Laudato Si' Goal "Community resilience and empowerment."

When I directed the Collaborative Center for Justice, a social justice organization founded by Catholic women religious, we participated in a successful statewide advocacy campaign to fund upgrades to Connecticut's affordable housing stock. They were aimed at remediating common environmental hazards found in old units, such as lead and rayon, as well as subsidizing energy efficiency upgrades, such as solar panels and insulation.

As a Catholic organization, we were proud to advocate for state Senate Bill 356, an act to establish an energy efficiency retrofit program for affordable housing, because, as proposed, it fit Pope Francis' model for climate policy solutions: It aimed to reduce the state's greenhouse gas emissions in a way that privileged the interests of Connecticut's working-class residents.

People of faith have to build upon the person-by-person, institution-by-institution engagement with environmental issues that has been fruitful in congregations by further entering the fray of politics.

The magnitude of the crisis demands that we prioritize political action to regulate producers and have our policy priorities align with the masses of working-class people.

The pope's vision of integral ecology does not see poverty reduction and climate change reversal as two separate tasks. Rather, he says in his 2015 encyclical, "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," "Strategies for a solution demand an integrated approach to combating poverty, restoring dignity to the excluded, and at the same time protecting nature."

We must pursue policy aims that operationalize the preferential option for the poor. Unfortunately, not all policy solutions take this as a starting point. As I see it, there are three prevailing alternatives on the U.S. policy scene.

First, there is what has largely been the U.S. response: little to no action to reverse climate change, with some efforts at adaptation. The quiet part no politician wants to say out loud is that "we" aren't facing "a" climate crisis. There ain't no "we" — not a single person that will be impacted equally by the changing climate.

Western militaries have been most forthcoming about this. Since the release of its 2012 "Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap," the Pentagon has been preparing for the likely "greater competition for more limited and critical life-sustaining resources like food and water" brought on by a changing climate. Many of the would-be immigrants who have faced militarized responses from our government at the southern border are themselves climate migrants from the so-called "Dry Corridor" of Central America.

Advertisement

The second approach claims that population growth from poorer communities exacerbates not only poverty, but also the climate crisis. But as the Union of Concerned Scientists notes, this assumption allows the countries most responsible for the changing climate — both historically and at present — to evade responsibility for the impacts. It assumes that people are equally responsible, so the poorer, darker nations producing more people are to blame.

In fact, the opposite is true: The richest individuals are responsible for the greatest emissions. Without changes to their consumption patterns, the International Energy Agency notes, the top 10% of emitters alone will blow through the carbon budget needed to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

The final policy approach aims to use technology to reverse the changing climate while making minimal changes to consumption and production patterns. It is part of what Francis describes as uncritical faith in technological advancement, grounded in delusions of human grandeur. That may seem harsh, but some technological solutions proposed are aimed at maintaining the continued expansion of Western consumption.

The same people who can't manage to keep social media platforms from imploding on themselves are planning to "solve" climate change by doing things such as altering how much sunlight reaches the Earth by releasing tons of aerosols into the atmosphere or controlling the weather by seeding rain clouds into drought-stricken areas. Indeed, the primary measure of success in capitalist economies — gross domestic product — is a measure of consumption.

One last approach worth mentioning is personal and institutional concern for so-called carbon footprints. This is a solutions framework that we need to build upon and subordinate to collective political action.

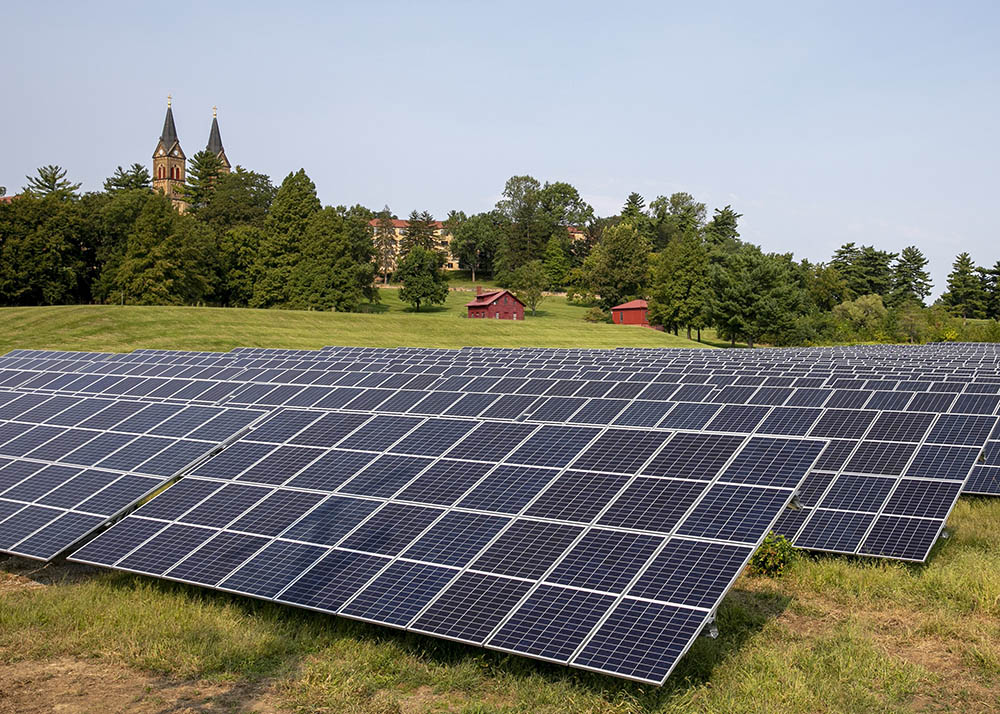

Solar panels are seen on the campus of St. Meinrad Archabbey and its seminary in Spencer County, Indiana, Sept. 11, 2021. (CNS/Courtesy of St. Meinrad Archabbey via The Criterion)

People of faith have been remarkably successful at transforming the institutional lives of their houses of worship. For example, a February 2023 Berkeley Labs report found that houses of worship host a disproportionately high rate of solar panels when compared to other nonresidential buildings.

But even this study's findings capture the limitations of a personal or institutional morality model: Houses of worship with solar arrays were disproportionately located in relatively wealthy, white and educated census tracts. We need to reverse this reality. Politics is the way we do that.

The harms of this model in a vacuum are many, but two important ones stand out. It immobilizes us politically by encouraging us to focus on personal and institutional consumption. In doing that, we lose focus on government and corporate actors. This framework was formulated by one of history's most prolific polluters, British Petroleum, in consultation with the public relations firm, Ogilvy & Mather. It even included a website you could use to calculate your annual emissions.

What BP's calculator will not tell you is that the U.S. military is the world's greatest institutional consumer of fossil fuels and, therefore, the most prolific emitter of greenhouse gases. It shouldn't be surprising that the company would not want to alienate its industry's best customer, I suppose. As noted in a 2019 Watson Institute report, these emissions are generated during our perpetual warfare, in the maintenance of the nation's 800 plus military bases, war games and noncombat operations.

Centering working-class people is more than just ethical, it is politically expedient. We are the majority, and we are not doing well.

Congress' allocation of federal dollars to maintain this self-destructive state of affairs is actionable only to citizens, not consumers. The magnitude of the crisis demands that we prioritize political action to regulate producers and have our policy priorities align with the masses of working-class people.

Whether we like it or not, the policies we pursue dictate the allies we choose. Take transportation, which accounted for the largest share of greenhouse gas emissions (28%) in 2021, for example. By the end of 2022, the average electric vehicle cost $61,488. That is wholly irrelevant to the lives of many people. One has to wonder who an EV policy priority is for, because it is not for the majority of the population.

A campaign to overhaul the nation's too-small and retrograde public transportation infrastructure, on the other hand, would improve the day-to-day lives of more people who need it most. Both the rural and urban poor, the elderly and children increasingly find themselves stranded and unable to access basic human needs due to lack of transportation options. Personal EVs won't help them. Electrified fleets of public buses can.

Centering working-class people, as Francis advises, is more than just ethical, it is politically expedient. We are the majority, and we are not doing well. Indeed, among workers, most are either living through a financial crisis or on the precipice of one.

Any integral approach to either poverty relief or to the climate crisis must address the other as well, and in so doing, create the conditions for a broad-based, diverse movement.