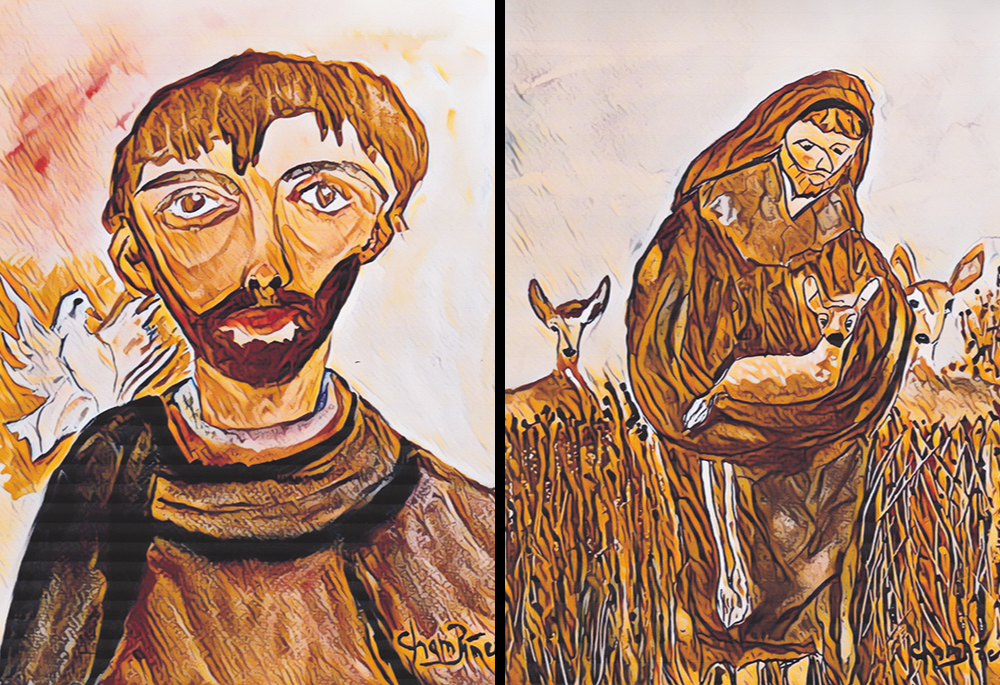

Illustrations by co-author Frank Champine, from the book Singing with Crickets: Meditations on Francis of Assisi and Nature (Frank Champine)

When I was a student at St. Mary's College, I had a theology professor who hated the shepherd-sheep metaphor for Jesus and his followers.

The professor's issue with the idea of Christians as sheep was that, in his words, sheep are stupid. Sheep will follow a designated leader regardless if that leader is offering good guidance, he said, saying that sheep cannot think critically for themselves. Therefore, to him the shepherd-sheep relationship does not paint Christians — or Christ — in a favorable light.

For the past decade, I have more-or-less adopted this perspective myself, avoiding use of the sheep metaphor and smirking a bit when I hear others use it. That is, until I read Singing with Crickets and was presented with a more compelling and complimentary characterization of sheep. Perhaps our fellow creature the sheep is admirable after all — at least that's the conclusion I've reached when considering the concept through the perspective of St. Francis of Assisi.

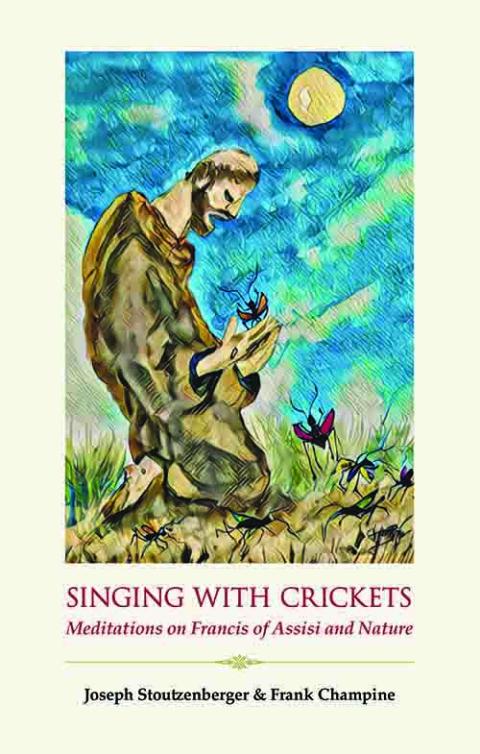

Cover illustration for Singing with Crickets: Meditations on Francis of Assisi and Nature (Frank Champine)

In Singing with Crickets: Meditations on Francis of Assisi and Nature, Joseph Stoutzenberger and Frank Champine explore the words, tales and prayers of St. Francis in a way that forces readers to ask themselves if and how this well-known Catholic figure and patron saint of ecology can be a model for eco-conscious living today.

The 22 reflections in the book are concise, no longer than a page each, and all are followed by a paragraph-length prayer that contains a one-line Scripture reference.

But my favorite part of the meditations may be Champine's paintings sprinkled throughout the pages and paired with short poems. This visual addition to the written reflections pushed my meditations a step further than did the words alone. And more than once I found myself wondering if the prints are for sale.

The way Singing with Crickets is organized makes it ideal for study groups or classes who want to spend a day or a week pondering individual meditations that the book explores: about worldly delights, the universe groaning, simple living, rebuilding the planet, wind and weather or pardon and peace.

As someone who struggles to find time to sit down and read a significant portion of any book at one time, I found this book convenient for my own personal use, being able to fit short meditations sporadically throughout the week and then reflect back on them throughout my days.

Advertisement

I also appreciated the list of organizations to consider at the end of the book, which directs readers to continue exploring the topics of protecting and preserving the environment within a framework of faith. (Thanks to Joseph and Frank for including EarthBeat among these resources!)

As for my feelings about sheep, Stoutzenberger and Champine's main point about the wooly livestock is that sheep instinctively stick together. They follow a leader not because they are stupid, but because they know that isolation makes them vulnerable while togetherness keeps them safe.

And when the authors say that sheep know "The wellbeing of one depends totally on the wellbeing of all," they aren't asking us to just apply this to humanity, but rather to all creation.

I'll never think about sheep the same way again.