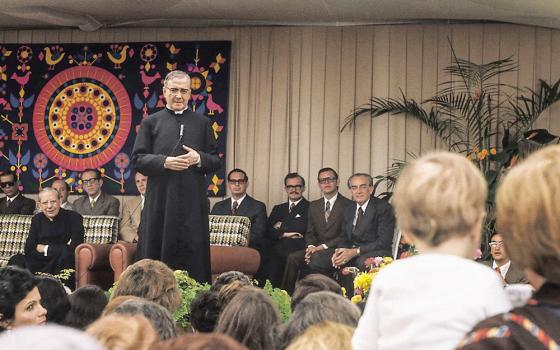

Los Angeles Cardinal Roger Mahony addresses the U.S. bishops as they wrap up their final day of meetings in St. Louis in June 2003. (CNS/Reuters)

In 2003, with the country newly focused on the sex abuse scandal in the Catholic church, a senior U.S. church leader attempted behind the scenes to head off the investigation of the crisis by researchers at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, disparaging the institution and its researchers as inadequate.

Los Angeles Cardinal Roger Mahony, in a strongly worded letter to then-Bishop Wilton Gregory, at the time president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, complained at length about the forms that John Jay researchers produced. He described them as "designed by people who apparently have no understanding of the Roman Catholic Church, ecclesiastical culture, hierarchical structure, or the language of the Roman Catholic Church."

The previously unpublished letters that circulated among Mahony, Gregory, former Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating, Justice Anne Burke and others provide a behind-the-scenes view of some of the tensions in the air the year after the U.S. bishops formulated their Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People during their June 2002 meeting in Dallas. Public outrage had forced the bishops to take a dramatic step to deal with the scandal of sexual abuse of children by priests and the cover-up of the abuse by scores of bishops across the United States.

The letters are part of Burke's archives, held by DePaul University in Chicago. Burke, a member of the Illinois Supreme Court, initially served as vice chairperson of the National Review Board for the Protection of Children and Young People, established under the charter. She later took over as chairperson when Keating resigned. The correspondence provides a window into the high-stakes tensions of that period, as questions swirled regarding the board's independence and whether bishops would cooperate with or undermine investigations.

In an April 4 phone interview, Burke said she thought the letters would provide further insight, given the recent disclosures in Los Angeles, of hierarchical attitudes in dealing with the crisis.

She described Mahony at the time as "an obstructionist" and said he represented "a pattern of conduct of circling the wagons so they [the bishops] could protect the clerics and themselves. The first thing they thought of in every instance was 'protect, protect, protect,' and not about the truth or the victims."

Mahony apparently had written letters and made a phone call to Kathleen McChesney, the first director of the U.S. bishops' Office of Child and Youth Protection, in January 2003, urging that such forms be reviewed "by a large number of" dioceses before being used to survey the dioceses. That didn't happen, and in an April 23, 2003, letter to Gregory about the John Jay study, Mahony wrote, "One could even surmise that the ill-conceived and poorly thought-out questions were designed to create a further media 'feeding frenzy.' It almost seems that the forms were designed, on purpose, by people who have a vested interest in confusing the many intricate issues and maximizing the statistical number of perpetrators, as well as attaching the greatest possible numbers of perpetrators to Diocesan Reports."

Mahony also expressed fear that the information being collected by John Jay researchers, though it went through an elaborate system to disguise the dioceses and keep accused perpetrators and victims anonymous, would be both leaked and subject to legal discovery.

He was convinced that "perpetrators will almost certainly be reported multiple times, as both Religious Orders and Arch/Dioceses report the same person in accord with the present format." He was also certain that the procedures would mean "that statistics -- and indeed, individual records, will be attached to reporting Dioceses and that individual Diocesan and/or Religious Order records will become discoverable in both criminal and civil legal actions."

Gregory, who was then bishop of Belleville, Ill., and is now archbishop of Atlanta, apparently wrote a response on April 24 that didn't satisfy Mahony.

The following day, the cardinal sent another letter that, while expressing his agreement with the necessity to collect "valid data and information about the extent of the sexual abuse of minors by clerics," still listed strong complaints about John Jay.

It repeated his disappointment that the forms in question had not been produced "by a top-flight Research Center, pre-tested with a large group of our Arch/Dioceses and Vicars for the Clergy." His own vicar, he said, was eager to help. Further, he said, his attorneys "have stressed that all of the pages and data sent to Jay College are fully discoverable by criminal prosecutors and civil attorneys, and that it would be very simple to 'connect all of the dots' to link clerics, victims, and dioceses."

As an alternative, Mahony advised canceling the contract with John Jay College in favor of "a nationally recognized Research Center." He acknowledged such a move "will cost far more money, but the results are ones which we would be able to support." He also repeated his wish that "at least 25" dioceses of varying size and their vicars for clergy be fully involved in the development of any forms used.

Finally, he said, if there were no way to cancel the John Jay contract, the conference should pay the fee "and abandon further contact with them." At that point, he said, the conference should use the existing forms as drafts and gather the experts from dioceses, as he had recommended, to develop "forms that are realistic and which will gather the data needed."

On May 9, Mahony received the backing of the bishops in the California Catholic Conference. In a resolution that passed unanimously, the bishops said they had "regrettably concluded that they cannot accept the proposed Jay Study process or survey instruments to accomplish their commitment to cooperate in a comprehensive study" mandated by the charter.

Meanwhile, Gregory wrote a brief letter of thanks, dated May 1, to Keating for allowing him to be the first respondent to Mahony's concerns. He was referring to an email that high-powered Washington attorney Robert Bennett had sent to other review board members regarding "what I view to be an outrageous letter" sent to Gregory by Mahony. "This letter was sent to all cardinals and United States Metro Archbishops," Bennett said, and its effect "is to basically give cover to those who do not want to cooperate with our Board. The Board, after much consideration, decided what information we needed. Cardinal Mahoney [sic] should not be an obstructionist. This unnecessary and unjustified attack on John Jay is absolutely irresponsible." Bennett wanted the board to immediately respond to Mahony.

Support for review board

Gregory wrote to Keating, "It was essential that I be the one to respond to a letter addressed to me, taking the opportunity to reassure him and any other bishops who might be struggling with how they might best respond to the forms completely and accurately." Gregory also noted that he took the opportunity in his letter to the cardinal "to reinforce the importance of the role of the National Review Board" and "to urge strongly for Cardinal Mahony's cooperation with this important project."

Gregory sent a note to Bennett on May 23 voicing "my heartfelt thanks for your very generous service on the National Review Board. Though there have been some very difficult moments along the way, I am grateful to you for your readiness and willingness to seek the positive solution."

That same day, Gregory faxed a seven-page, point-by-point rebuttal to Mahony. The letter was based in part on responses Gregory had received from John Jay College officials, including the chief researcher for the project, to whom the board had sent a copy of Mahony's concerns.

Regarding John Jay College's inexperience with the Catholic church, Gregory told Mahony that he agreed with the National Review Board's reasoning "that it was essential to select a non-church related research organization to guarantee the utmost objectivity of the study."

He further argued that John Jay was expert in carrying out such studies and in such a way that protects privacy and confidentiality. The college itself had a stake in protecting confidentiality, he wrote, because "any leak of information from John Jay College or its researchers would not only destroy their ability to complete this project, but will jeopardize their standing in the academic world."

Gregory noted that the questionnaire had been reviewed by the Office of Child and Youth Protection, the National Review Board, the Ad Hoc committee on Sexual Abuse (which included 15 members of the bishops' conference), officers of the Major Superiors of Men, and the bishops' conference staff in Washington.

Only the principal investigator in the project would have access to encrypted information about individual clerics that could lead to further identification, according to Gregory. That person, he said, had signed a letter of confidentiality and was protected from disclosing information by a federal "certificate of confidentiality." Further, Gregory said, all identifying formation "will be destroyed at the conclusion of the research.

On May 5, 2003, Keating weighed in on the controversy with a letter to Gregory as a response to the Mahony criticisms. Keating's response covers much of the same ground, though in less temperate language, describing the cardinal's objections as "puzzling," "unfair," "without any basis in fact," and "unjustified and baseless."

Keating said, "While Cardinal Mahony is possessed of expertise in many areas, the Board places greater weight on the expertise of John Jay and others rather than Cardinal Mahony in this area. We are fully satisfied that adequate pre-testing was done."

Mahony, in an April 9 email response to questions, told NCR that the "coding and processing systems originally proposed were very inadequate, and actually, John Jay College responded to the concerns of the diocesan bishops and attorneys and improved the research instruments greatly, thus avoiding breaches of confidentiality that would have affected both victims and perpetrators."

In an April 8 telephone interview, Edward Dolejsi, executive director of the California Catholic Conference then and now, recalled that he and the conference's general counsel "were instructed to go back and meet with John Jay folks and members of the National Review Board." He said an arrangement was eventually worked out regarding "how we could cooperate." Ultimately the study was done with the cooperation of California's bishops, including Mahony.

Mahony told NCR April 9 that he had wanted an approach "far more expansive and inclusive" than that proposed by John Jay researchers. He said he had recommended the University of Chicago and the Pew Research Center "because they had a far broader capability in all phases of the church's inquiry than JJC, which as a small part of the NYU [New York University] system, it just didn't possess."

He described the John Jay College reports as "only moderately adequate" and maintained that the reports did not receive much notice. "Virtually no one in the country had heard of JJC, and most media ignored their reports and the information."

'Criminal conduct'

In his May 2003 letter to Gregory, Keating took special exception to Mahony's claim that the forms were designed to create a media "feeding frenzy" by people "who have a vested interest" in making the crisis seem worse than it was. "Implying that the crisis is the result of a 'media feeding frenzy' is inaccurate. The crisis arose out of the criminal conduct of certain priests and the inadequate response of certain bishops to that conduct. Inaccurate and occasionally malicious reporting will always occur, but it is not surprising that the media have reported on this criminal conduct, and we do not believe it is constructive to blame the media for the problems of the church." The charter itself, Keating said, blamed the crisis on " 'the ways in which we bishops addressed these crimes and sins,' not by the ways in which the media have reported them."

Keating resigned in June 2003, a week after comparing bishops who did not cooperate with the board to the mafia. In his resignation letter to Gregory, he wrote, "My remarks, which some bishops found offensive, were deadly accurate. I make no apology. To resist grand jury subpoenas, to suppress the names of offending clerics, to deny, to obfuscate, to explain away; that is the model of a criminal organization, not my church."

Mahony wasn't finished with his criticism.

In March 2004 letter to McChesney, he objected to a characterization of the Los Angeles archdiocese as "another troubled diocese" in a report issued by the review board. He also objected to the statement, "Cardinal Mahony, the Archbishop of Los Angeles, had allowed numerous predator priests to remain in ministry."

"I cannot tell you how much incalculable harm has been done to the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and to me personally because of that paragraph," he said. "As you might well imagine, the Los Angeles Times interprets that single paragraph as a 'scathing indictment' of me and of the archdiocese -- not only for the sexual abuse matters, but for everything that has taken place in this archdiocese since 1985."

Concurrently, the archdiocese's law firm, Hennigan Bennett and Dorman, faxed a letter to Burke lodging the same complaints over six-and-a-half pages, including lengthy excerpts from an archdiocesan-generated report on the matter.

The archdiocese would eventually pay out $722 million in global settlements agreed upon in 2005 and 2007 with 550-plus victims in clergy abuse cases. The archdiocese would also eventually lose a protracted fight, the cost of which has yet to be revealed, to keep sealed thousands of documents that it had agreed to release as part of the settlements with hundreds of victims.

In January this year, following release of the documents, which showed Mahony had covered up for and transferred priests known to have abused children, the current archbishop, José Gomez, said he had notified his predecessor "that he will no longer have any administrative or public duties" in the archdiocese.

[Tom Roberts is NCR editor at large. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]