People camp in tents next to the Interstate 405 freeway March 31 in Portland, Oregon. (AP photo/Eric Risberg)

Editor's note: This is the first in a two-part series about chronic homelessness and permanent supportive housing. The second part will be published Dec. 12.

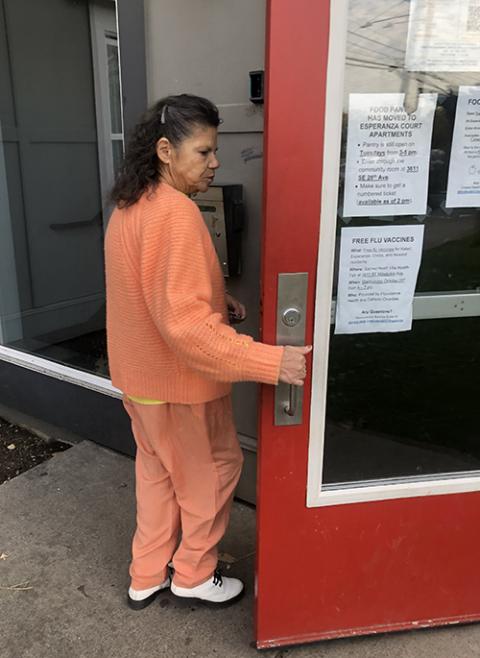

A refrigerator adorned with photographs and topped with a box of Honey Bunches of Oats. White doilies and a bouquet of artificial flowers arranged on a coffee table. A damp towel draped over the bathroom door. They are simple signs of a lived-in and thoughtfully decorated apartment, but for Sharon Browning they are also the trappings of a life rebuilt.

"When I was homeless, I would sleep on a bench with my purse, but everything got lost or stolen, even my clothes," said the 64-year-old as she opened her vinyl blinds, letting in the fall Pacific Northwest sunlight.

"I was trying to stay in motels but I didn't have an ID and I wasn't on medication, so I didn't know how to function," she said. "I'd never been on the streets before and didn't know how to defend myself."

Browning, who said she attempted to navigate her bipolar disorder with alcohol, eventually moved into housing that required sobriety.

"I couldn't get myself straightened up, so I got kicked out," she said.

Then Browning found an apartment complex managed by Catholic Charities of Oregon. It offered affordable housing coupled with supports to help individuals remain housed, and there was no sobriety mandate.

That was 17 years ago. Browning has lived there ever since and recently celebrated eight years in recovery.

As chronic homelessness escalates nationwide, advocates and researchers say a big part of the solution is the model that transformed Browning's life. Known as permanent supportive housing, the approach incorporates rent-restricted housing with a range of voluntary support services.

Sharon Browning sits in her Portland apartment this fall prior to attending a faith sharing group. After living on the streets and grappling with bipolar disorder and alcohol, Browning, now 64, found long-term stability in Catholic Charities-run permanent supportive housing. (NCR photo/Katie Collins Scott)

Catholic agencies helped develop the model decades ago, and in 2020, Catholic Charities USA launched a pilot aiming to reduce chronic homelessness 20% over five years in five cities, including Portland, in part by increasing the stock of permanent supportive housing.

While the Catholic pilot has made headway, there are challenges that limit the supply of permanent supportive housing and the effectiveness of programs that exist. Staffing shortages, inadequate funds, long wait times, the so-called NIMBYs and pushback tied to critiques of the "housing first" concept are among the hurdles.

Yet even with poor implementation, "it is still better than other options," said Marisa Zapata, director of the Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative and a professor of urban studies and planning at Portland State University. "Permanent supportive housing is the most evidenced-based solution to chronic homelessness that exists."

Assisting the most vulnerable

Not far from Browning's apartment building, a row of tarp-covered tents, parked rundown cars and other temporary shelters line a city block. Oregon has the highest rate of chronic homelessness in the United States, and nationally chronic homelessness rose almost 65% between 2016 and 2022, according to Department of Housing and Urban Development figures. The overall homeless population is disproportionately Black and Indigenous.

People classified as chronically homeless — usually those who've been without housing for at least a year and have a disabling condition, including addiction or mental illness — make up almost a third of the United States' total homeless population and are among the most vulnerable.

Homeless people talk outside on a couch July 5, 2022, in Portland, Oregon. (CNS/Bob Roller)

"Chronic homelessness is about ongoing daily survival," said Rose Bak, chief program officer at Catholic Charities of Oregon. "It's figuring out over and over where to get the next meal and take a shower, and then there's increasing violence against people on the street."

In Portland, winter and fall are always rainy and cool, and that leads to things like trench foot and other infections, Bak said. "Add to that the addiction and mental health crisis or other disabilities and life gets exponentially worse."

Early versions of permanent supportive housing emerged in the early 1980s as interventions for homeless individuals with mental illness, HIV/AIDS and chronic substance abuse. Over the years it's also been used to address homelessness in other at-risk populations, such as youths aging out of foster care and people involved in the criminal justice system. It is now often implemented for the chronically homeless.

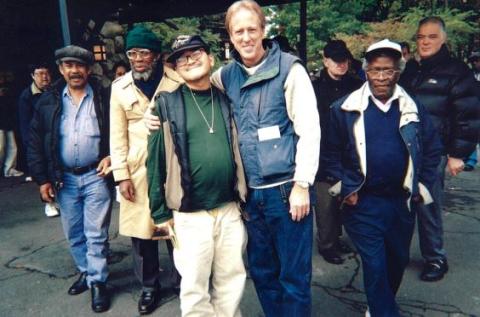

Franciscan Fr. Tom Walters, who helped found St. Francis Friends of the Poor in New York City, is pictured with tenants in the mid-1990s. (Courtesy of St. Francis Friends of the Poor)

Though the concept "is sort of an obvious thing, no one had tried it before," said Steve Berg, chief policy officer for the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

In November 1980, what is now St. Francis Friends of the Poor was opened in New York City by three Franciscan Friars who pioneered the idea of permanent supportive housing for homeless individuals with mental illness. According to a history compiled by the Supportive Housing Network of New York, between 1982 and 1986, Catholic Charities of Brooklyn and Queens redeveloped church-owned properties for supportive housing, a strategy used in Catholic Charities USA's current initiative.

Under the housing model, all or several units in an affordable housing apartment complex are for supported tenants, and services are onsite. There is also a scattered site model, where tenants live in subsidized private market apartments and nonprofits provide mobile services. Residents use about a third of their income for rent.

"If your income is $900 a month, you pay $300; if it's zero dollars, you pay zero dollars," said Sally Erickson, director of supportive services for Catholic Charities of Oregon and an expert on permanent supportive housing.

Construction, operation and the services of supportive housing usually are financed through a mix of federal, state and local funds, grants or loans from private corporations and financial institutions, and philanthropy.

Good Shepherd Village, which opened Nov. 6 in the suburbs of Portland, has 142 units of affordable housing, including 58 units reserved for permanent supportive housing. With funding from a $652.8 million housing bond passed by Portland area voters in 2018, Catholic Charities of Oregon staff will provide supported residents with a range of services and case management. (Courtesy of Catholic Charities of Oregon)

The federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit is one of the largest programs for creating new permanent supportive housing units, while rent is often subsidized with HUD- or state-funded vouchers.

Tenants are offered case management, and services range from utility assistance and child care to job training and psychiatric and substance abuse treatment.

Once housed, many people need help overcoming the trauma of homelessness and to relearn life skills like how to understand a lease or work a thermostat, Bak said.

"There also might be behaviors that made people feel safe on the street but don't work well in housing," she said. "Pushing someone who gets in your space might keep you protected while homeless but that could get you evicted in housing. We help people change those kinds of patterns."

Successes and setbacks

Permanent supportive housing and housing first frequently are conflated, especially in recent debates about homelessness nationwide, because many, though not all, supportive housing programs operate under the philosophy.

Housing first does not require people to accept services like treatment for mental illness or drug use as a condition of housing. In the early 2000s, President George W. Bush embraced the idea, and it became part of the national policy to address homelessness.

Sally Erickson is director of supportive services for Catholic Charities of Oregon. (Courtesy of Catholic Charities of Oregon)

"Housing first makes a lot of sense," said Erickson. "You are not able to be compliant in mental health treatment or addiction treatment or managing your health while you are living through the danger and chaos of being outside."

It took Browning several years of relapse and recovery before she was able to find long-term sobriety. "But I did it with a home and with support," she said.

Permanent supportive housing, like housing first, long received bipartisan support, and both Bush and Barack Obama put money into generating more units. From 2007 to 2020, the stock of permanent supportive housing beds more than doubled.

The result, say advocates: Between 2007 and 2016, chronic homelessness declined by more than a third.

Funds for supportive housing remained static during the Trump administration, however, and in 2017, the number of chronically homeless individuals began to move upward again, a trend that's continued through President Joe Biden's administration, which has allocated more — though advocates say insufficient — funds. The 2022 count of chronically homeless individuals surpassed all previously recorded years.

Advertisement

The increase, say Berg and other advocates, is because the housing market caught up with advances made in programs for the homeless.

"You can't really blame the increase on Trump," Berg said. "I think we accomplished a lot by creating better systems for the homeless — and we can still accomplish more because the homelessness systems don't have enough money to do what they need to do. For every 10 people who are moved into housing on a given day, 15 or 20 more people lose their housing."

There are limitations to some of the research on permanent supportive housing and studies that show mediocre success. There are also examples of programs that are seriously deficient.

Pascale Leone is executive director of the Supportive Housing Network of New York, a membership organization representing more than 200 nonprofits that develop and operate supportive housing. (Courtesy of Supportive Housing Network of New York)

Pascale Leone, executive director of the Supportive Housing Network of New York, said studies or examples that show poor or lackluster outcomes reflect not a failure of the model but obstacles agencies face implementing it.

"There are real challenges that can reduce the efficacy of some permanent supportive housing," she said. Still, "study after study" affirms that it "helps people get back on their feet and provides the best opportunity for them to find stability."

A 2023 paper summarizing a decade of findings about a program in New York concluded placement into such housing was associated with "improved physical and mental health outcomes, increased housing stability, and statistically significant cost savings per person after one year of placement."

Researchers at the University of California San Francisco found that 86% of the chronically homeless people placed in permanent supportive housing in Santa Clara County remained in their housing for the "vast majority" of the study follow-up period.

In Portland's Multnomah County, a new report found 99% of people the county moved into permanent supportive housing between July 2021 and July 2022 remained housed a year later.

With permanent supportive housing you are "treating those who have the most problems, who have been on the streets the longest, who everybody thought you couldn't help," Berg said. "Then lo and behold, if you give people housing and services, starting with what they ask for, lots and lots of people will become stable and never be homeless again."

Sharon Browning opens the front door to Kateri Park apartments in Southeast Portland. The affordable housing complex includes 20 units of permanent supportive housing. (NCR photo/Katie Collins Scott)

Robert McCann is president and CEO of Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington. The Spokane-based nonprofit is participating in Catholic Charities USA's initiative, and over the past two decades, McCann has helped his agency dramatically increase its supply of supportive housing.

The housing first model of permanent supportive housing aligns well with Catholic social teaching, said McCann. "Every person is made in the image and likeness of God, he said. "We don't care where you are from, what your background is, we are going to serve you and care for you."

On a recent afternoon, Browning sat in Catholic Charities of Oregon's drop-in center for homeless women and visited briefly with Victoria Waldrep, the longtime manager of homeless and transitional housing services.

Over the years Catholic Charities has "always been there," said Browning. "If I have questions about a hospital bill, need assistance with bus fare, they help. If I needed some hot food, they would feed me. They also just say, 'How are you doing today?' They make you feel special."

Waldrep leaned in toward Browning. "Well," she said, "that's because you are."

Editor's note: Part 2 of this series examines Catholic Charities USA's initiative to address chronic homelessness and some of the challenges that hinder permanent supportive housing efforts nationwide.

[This article was made possible by a grant from the Hilton Foundation.]