Detail of painting "The Missionary's Adventures" by Jean-Georges Vibert. circa 1883 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The "Catholic sex abuse crisis" is not a crisis. A crisis is a temporary period or series of events of an unstable and dangerous nature. It passes and the original situation is either better or worse than before.

Violations of the Christian obligation of chastity by clerics have been part of the life and culture of the Christian community since the first century. Throughout the two millennia of church history, the leadership elite — popes, bishops, abbots et al. — have tried in a variety of ways to keep the various violations covered by secrecy. History has shown that their success rate has been inconsistent.

Prior to the 1970s, public knowledge of the Catholic clergy's problems with celibacy had been largely limited to occasional stories of priests who have left the priesthood to marry or who were caught in an illicit relationship with a woman. Wrapping a good Catholic mind around the real possibility of the sexual violation of a child or a young adolescent by a priest was close to impossible in the 1940s, '50s, '60s or even in the post-Second Vatican Council '70s.

The invisible but thick wall of secrecy began to crack in 1984 when revelations of multiple cases of sexual abuse of male children and young adolescent boys surfaced about Thomas Adamson in of the Archdiocese of St. Paul-Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Gilbert Gauthe from the Diocese of Lafayette, Louisiana. The secular media and the civil legal system got involved. The cracks in the wall rapidly spread, and the wall started to crumble. The rest is history, as they say — or is it?

What was surfacing was not a crisis that prayer, papal and episcopal exhortations, policies, programs or even apologies, sincere or not, would or could stop. Instead, a very dark and destructive dimension of the institutional church was revealing itself. The shock and anger of many was accompanied by the demand for answers. The first wave was focused on the perpetrators themselves. The hierarchy, from Pope John Paul II to the local bishops, conjured up excuses but provided no credible reasons why clerics violated children and why bishops were incapable and unwilling to respond in an effective, compassionate and intelligent manner.

The conversation that centered around the reasons why changed significantly in 1992 with the publication of Jason Berry's landmark 1992 book Lead Us Not into Temptation and in 1995 with the publication of Richard Sipe's breakthrough work Sex, Priests and Power and Anson Shupe's groundbreaking sociological study In the Name of All That's Holy. All three authors went beyond the stories of sexual abuse to the real issue, the systemic dimension of what we now know to be a churchwide and timeless phenomenon.

In the space of the next three decades, hundreds of books and scholarly articles appeared, many of which were significant contributions to the comprehensive search for what this phenomenon is all about. Those who tried to minimize the issue, shift the blame or make excuses got no traction. The leadership ranks of the institutional church added nothing of true value to the search, beyond defensive and self-serving pronouncements.

Advertisement

The lens had focused on accounts of sexual predation and on the Catholic and clerical culture of the present era. Hardly any scholars or academics have taken the longer view, looking into the church's history from the primitive church to the early modern period. Sipe, Patrick Wall and I attempted an historic overview with Sex, Priests and Secret Codes (2006) in which we singled out a small number of texts from the fourth through the 17th centuries in our attempt to show a continuity of official church awareness and concern for clergy sexual abuse.

It turns out we exposed only a tiny tip of a massive iceberg. The bulk of that iceberg, which is hardly a solid mass but a mind-bending quagmire of little- and not-so-little-known documents from the primitive church to the late medieval period (third through 16th centuries), contains a landscape of the church that holds answers to most of the vexing questions that put our experience of sexual abuse into an entirely new light. The search for answers and explanations has been taken to a radically new and previously unstudied level by the intensive and extensive research of Dyan Elliott, a medieval scholar from Northwestern University.

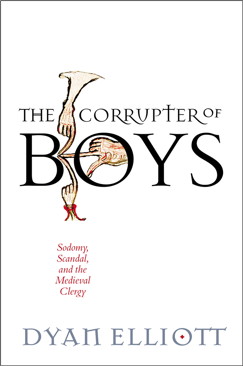

The results of her research are nothing short of remarkable, stunning and most importantly, authentic. The results are in her new book The Corrupter of Boys, being released this month by the University of Pennsylvania Press. I have been privileged to read an advance manuscript of it. I will readily admit to having been obsessed with discovering and exposing every historic layer of the key elements of the systemic causes of the sexual abuse phenomenon. This requires plumbing the church's legitimate and unrevised history to its depths. Elliott has done this, and her work changes the conversation in dramatic and invaluable way.

Here are some highlights of Elliott's key findings that have a direct and unbroken connection to the present.

In our era, the consistent and depressing pattern of response to the sexual violation of minors, mostly boys, has been the indifference to and even rejection of the victims and their families by the hierarchy and majority of the clergy. Hundreds of victims wrote letters to Pope John Paul II begging only for recognition of their plight. The now-canonized pope not only never responded, the correspondence was never even acknowledged.

Double helix staircase in the Pio Clementino Museum at the Vatican, designed by Giuseppe Momo, sculpted by Antonio Maraini and realized by the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry in 1932, pictured in 2004 (Wikimedia Commons/Andreas Tille)

This scandalous attitude is not new, but a contemporary manifestation of attitudes and behaviors that reach back to the fourth century. Elliott found scant evidence of sincere concern for the welfare of victimized children through the centuries. On the contrary, it was common to blame the victims, often labeling them as seducers of clerics while they were devalued as human beings and treated as sexual toys or substitutes for women, unavailable (in theory) to official celibates. In those rare instances where the perpetrating cleric was actually punished in some way, the victim usually received a harsher penance.

The dehumanizing of children and the minimization of clerical pederasty, a pattern evident in the contemporary church, is an infuriating strain that has persisted from the primitive era down through the centuries. It is inextricably linked to the clergy's self-exaltation, which has its roots in the fourth century and is directly linked with the belief that their sacred office exempted priests and bishops from accountability. Manifest examples of the insistence on clerical entitlement in our era are a deeply entrenched part of the clerical subculture. Much of this entitlement is based on a theology of priesthood that is largely magical in nature.

Clerical pederasty was tacitly condoned from late antiquity to the late medieval period, but this condonation did not end there. It has persisted through the ages. The default response to reports of clerical abuse in our era, until very recently, has been to insist on absolute secrecy, ignore the damage to the victims, secretly move the priest and, above all, avoid scandal which, translated, means avoid any tarnishing of the hierarchical image. The bishops rarely, if ever, applied the mandatory sections of canon law that demanded an investigation into any type of report of sexual abuse and the possible application of penal procedures.

This, too, is nothing new. Prosecution of a priest for a sexual crime in the medieval tribunals was exceedingly difficult due to the degree of proof required because the accused was a priest. Consequently, convictions for pederasty were exceedingly rare not because it didn't happen — because it certainly did — but because it was far more important to protect the priest. It is no surprise that the church has staunchly opposed reporting clergy abusers to civil authorities, another symptom of narcissistic entitlement and obsession with image.

Elliott demonstrates, with massive documentary evidence, the church's obsession with clerical celibacy from the third century, and its direct influence on the corruption of boys. Though clerical pederasty was common, it was rarely prosecuted. The church's mission was not the welfare of children, but bolstering clerical celibacy by, among other things, trying to prevent married priests from having sex with their wives and stigmatizing their children. It was far more politically correct to attack clerical wives than to root out the culture of clerical abuse of the young. Woven through all of this, as we clearly see in The Corrupter of Boys, is the bizarre teaching on human sexuality promoted by church fathers such as St. Augustine and St. Jerome, and a deeply embedded attitude of highly toxic misogyny.

The Corrupter of Boys does not refer to a person but to an ecclesiastical and clerical culture. The destructive elements of this culture and its supporting theology have been deeply embedded throughout the church's history. Elliott has opined, with nearly 2,000 years of solid evidence, that "the corrupter of boys" is both incorrigible and untouchable. Perhaps she is right, but the corrupter of boys can still be isolated, and its power stonewalled.

[Thomas P. Doyle, a canon lawyer and inactive priest, has long served as an expert for lawyers representing victims of clergy sex abuse.]

*This story has been updated to remove an erroneous publication year for The Corrupter of Boys.