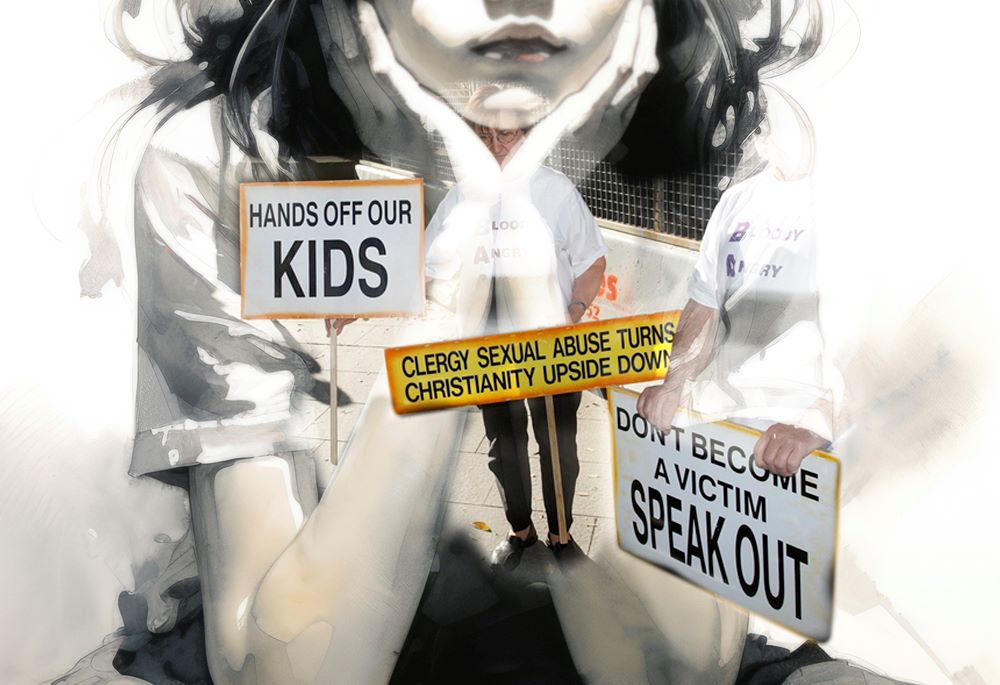

(NCR digital enhance/rastudio/CNS/Paul Haring)

Editor's note: This is the second in a two-part series about survivors of color and the clergy abuse crisis. The first part is available here.

"The seminal traumatic event I have endured as an adult."

That is how Deborah Rodriguez describes her experience reporting childhood sexual abuse to church officials a decade ago.

"Many Latinos have storytelling as part of their tradition," the 58-year-old said. "My story was not honored. It was ripped apart."

Deborah Rodriguez is pictured as a 6-year-old on her first Communion day, a few years before she was molested by a Catholic priest. When Rodriguez reported the abuse to church officials in her 40s, it was another form of trauma, she told NCR. (Courtesy of Deborah Rodriguez)

To make the first phone call or reach out to another person about abuse by a Catholic priest takes a staggering amount of courage for any victim.

But Black, Latino, Indigenous, and Asian and Pacific Islander survivors, who scholars say have been disproportionately harmed in the clergy abuse crisis, frequently face additional barriers to coming forward, scholars and survivor advocates told NCR. And when victims of color do report their abuse, they too often encounter church staff who lack sufficient trauma-informed and culturally sensitive expertise.

Fr. Bryan Massingale, a theology professor at Fordham University in New York City, said preconceptions about Black people often create " a kind of presumption that in many cases the victim did something to bring this on." (CNS/Fordham University/Bruce Gilbert)

"If the church is to do justice for all who are affected by this scandal, then we must ensure that all are adequately cared for — and receive the care that their specific circumstances demand," said Fr. Bryan Massingale, a theologian at Fordham University in New York who is conducting a study on Black survivors of clergy sexual abuse.

"For me," Rodriguez said during a recent interview, "I felt like I was completely assaulted again."

Obstacles to reporting abuse

Audit findings published in the U.S. bishops' 2022 annual report on the implementation of the "Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People" show a "steady decline" in the number of current allegations involving minors and allegations of a historical nature. The charter was adopted by the bishops in 2002 in response to the sexual abuse crisis.

But clergy abuse advocates and scholars told NCR they believe many victims of color have yet to come forward due to cultural and social barriers.

"I don't think anyone understands how many survivors have yet to tell their story of abuse," said Rodriguez, a physician and medical missionary who is developing a bilingual ministry for other survivors. "These are victims from both a generation ago, before the charter, as well as since the charter, and they are predominantly non-white and include immigrants, including those who come from other countries where they were abused."

The scarcity of demographic information about survivors makes it challenging to study and compare the barriers victims of color face when it comes to reporting abuse, scholars told NCR.

"Until we have more data, it is nearly impossible to say what the threads connecting these experiences are other than the racism that people of color have always experienced in the church and the fact that these voices have been neglected for all this time," said Tia Noelle Pratt, a sociologist and expert on Black Catholics and systemic racism in the Catholic Church.

Still, what emerges from interviews with experts and survivors of color are overlapping realities — shame, secrecy, a high esteem for elders, structural power disparities and complicated relationships with law enforcement — that make disclosure especially difficult.

Eunice Park is a Korean American in the San Francisco area who has worked in Asian and Pacific Islander ministry at local and national levels.

"It's hard to lump all API communities together, but generally speaking shame is the backbone in terms of how the cultures work, and I think the basis of that is the sense of communal identity," Park said. When one member of the community is victimized, "it can bring shame on the whole community."

Aimee G. Torres, who was molested by a Los Angeles archdiocesan priest from ages 8 to 11, said clergy were so idolized in her strict Filipino Catholic family they were seen "almost like a gatekeeper to heaven."

"I was worried I'd be disowned if I said anything," Torres told NCR.

Eunice Park, a Korean American in the San Francisco area who has worked in Asian and Pacific Islander ministry, said shame plays a strong role in many API communities. (Courtesy of Eunice Park)

Like Asian and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics are similarly a diverse people, with numerous histories and cultures and several ethnicities, Rodriguez said. "We are also a people of many vulnerabilities, and abusing clerics took advantage of that."

She referred to "the three Ss," standing for stigma, secrecy and silence. There's a stigma associated with seeking support for mental health and around abuse, fear of bringing shame upon families, and silence to protect a family's honor, she said.

Scholars said immigrant communities remain extremely vulnerable to abuse and confront numerous impediments to reporting it.

Susan Bigelow Reynolds, an assistant professor of Catholic studies at the Candler School of Theology at Emory University at Atlanta, studied a case from several decades ago in which an abusive priest threatened to deport a victim and his family if he reported the abuse.

Reynolds said much has changed in terms of how victims report clergy abuse, "but a lot has changed in the immigration system, too — and not for the better."

Often the church is one of few advocates immigrants have in this country, she said, and priests and other church leaders occupy unique, sometimes singular positions of trust.

"That means that church leaders wield a tremendous amount of power," said Reynolds. Since undocumented migrants don't have access to the police, courts and media, if that trust is violated, they have nowhere to turn for justice.

They also don't have clarity about how diocesan abuse-reporting structures interface with the legal system. Reynolds said they might wonder: "If I report abuse, does that mean the police will get involved and find out I'm undocumented and turn me over to ICE?" or "Can I trust that an abuse-reporting hotline is truly anonymous?"

"All of this creates a situation of profound precarity," she said.

Other racially and ethnically marginalized communities likewise face obstacles to interacting with the police and U.S. legal system.

Franciscan Fr. Linh Hoang, a professor of religious studies at Siena College in New York and consultant to the U.S. bishops' Subcommittee on Asian and Pacific Islander Affairs, pointed out that certain traditional medical practices in the Asian community, such as cupping — used to promote blood flow and muscle simulation but that can leave marks on the skin — have led to allegations of child abuse, making some families wary of reporting clergy abuse to police.

Massingale noted the "long legacy of suspicion of law enforcement and police departments in the Black community in general."

"Why would a survivor go to a justice system that they are already deeply suspicious of?" he said.

As in immigrant communities, Massingale added, language plays a role as Black survivors report abuse.

"If you are perceived as not being able to speak standard white English — if you sound Black, to put it bluntly — then you are not going to be seen as credible when reporting abuse," the priest said. "If you come across as too angry, then you are the 'angry Black man' or 'angry Black woman' and not seen as credible."

Bodies of color also are sexually coded in our society, said Massingale, with women seen as being loose and promiscuous and Black men seen as sexually rapacious and irresponsible.

"Therefore there is a kind of presumption that in many cases the victim did something to bring this on," he said.

Deborah Rodriguez is a Washington-based physician and a survivor of clergy sexual abuse who is developing a bilingual ministry for victims. She said the church needs to improve its use of trauma-informed, culturally sensitive care to survivors. (Courtesy of Deborah Rodriguez)

'A matter of justice'

In her ministry and work as a physician, Rodriguez walks with survivors, many of them Latino, from across the country as they try to report their abuse to church officials. She has contacts in numerous dioceses and has studied best practices for assisting sexual abuse survivors.

The Catholic Church has made progress in offering more trauma-informed, culturally sensitive care to survivors since she first reported her abuse a decade ago, Rodriquez said.

"But is it enough? No, it's not," she said. "It is still very much a minority of dioceses and archdioceses in the United States that offer such ministry."

"Sadly, many white people find it difficult to hear stories of race-based trauma sensitively and compassionately," Massingale said. They may react defensively about any discussion of race or racism, he said, and such a response can deepen the trauma survivors of color endure.

There also remains a lack of transparency in the church about the reporting process, according to Rodriguez. "These are sacred stories, and it's important for survivors to know that theirs will be honored and what will happen with their stories when they come forward," she said. "They are not always told."

Trauma-informed care acknowledges that present and past life experience, including cultural, physical and social environments, influence how people respond to traumatic events "so as to not retraumatize individuals," Rodriguez said. It is a standard of care that's been around more than four decades and is now being used in medicine, mental health treatment and law enforcement. Yet the Catholic Church, Rodriguez said, remains far behind in embracing it fully.

Survivor advocates told NCR such a comprehensive approach is vital to all victims, but it's imperative for survivors of color, who often carry layers of trauma from their cultural, social and immigrant experiences.

It is crucial to provide trauma-informed, culturally specific care to survivors of color "as a matter of justice," Massingale said. "Many cannot process their abuse without also speaking of the racism that compounded the harm. Many cannot heal of the sexual trauma without also dealing with how such traumas are received or understood in their racial or ethnic communities."

The diocesan victim assistance coordinator position was established by the bishops' 2002 charter, and for the past two decades the coordinators often are the first contact survivors have with church staff when making a formal complaint of abuse and seeking pastoral care.

Pope Francis speaks about abuse and survivors of abuse in a video released March 2. (YouTube/The Pope Video)

According to Heather Banis, a victim assistance coordinator for the Diocese of Los Angeles and a consultant to the U.S. bishops' Committee for the Protection of Young Children and Youth, the background of victim assistance coordinators "varies pretty dramatically" across the United States, with each bishop or archbishop dictating what happens in his episcopate.

The charter mandates that each diocese/eparchy "have a 'competent person,' but what that means looks different" in various regions, said Banis, a clinical psychologist who specializes in trauma. She views some coordinators as "outstanding" when it comes to trauma-informed care, while others need more training.

Among coordinators "I witness mentoring and a willingness to learn and share strategies," added Banis.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops did not respond to questions from NCR about diocesan-level requirements for victim assistance coordinators.

Bishop Mark Seitz of El Paso, Texas, kneels at El Paso's Memorial Park holding a "Black Lives Matter" sign June 1, 2020. Seitz said his diocese is struggling to find a victim assistance coordinator with the appropriate skills to work with people of color. (CNS/Courtesy of Diocese of El Paso/Fernie Ceniceros)

Bishop Mark Seitz of El Paso, Texas — whose display of solidarity with the racial justice movement in 2020 spurred a phone call from Pope Franics — told NCR his diocese's longtime victim assistance coordinator is retiring, and it's been challenging to find a replacement with the right mix of skills.

"I suspect other bishops find it difficult, as well," Seitz said. In larger metro areas with more resources it might be easier, he said, but "it's a pretty rare skill set in a profession that's already underserved, and this particular person needs to have compassion and faith, the ability to really deal with someone who comes in with raw wounds."

Massingale — who found through his research a significant need for more culturally competent individuals to work with Black survivors — said he believes that if diocesan officials are not able to offer appropriate accompaniment for survivors of color, then the diocese should outsource the ministry to bring in people who can provide culturally sensitive care.

Advertisement

The priest learned in his studies of an instance in a U.S. diocese where individuals charged with responding to victim-survivors "admitted they were afraid to go into the Black community, that they were uncomfortable with meeting Black men who were victims of sexual abuse by clergy."

"That's one diocese that I know of," Massingale said. "How many others are there? I would suspect that's more the rule than the exception."

He also has heard African American survivors bristle at the term "survivor." He suggests "coper" as a more culturally sensitive alternative.

"Coping" is a term many African Americans use to talk about how they get along in a white world "that's indifferent to our situation, to our plight," Massingale said. "We say, 'I'm coping,' 'I'm getting along,' 'I do what I have to do to get by.'

"We need to look at the language we are using and find language that will resonate," he said. But diocesan officials taking the lead in formulating a response to survivor-victims lack cultural competency, he said.

A key reason for that deficiency is the absence of Black Catholics in most leadership positions, according to Pratt, the expert on Black Catholics and systemic racism.

"Why is it that Black leadership in our diocesan chanceries begins and ends with the Office of Black Catholics, if there even is such an office anymore?" she said. "Many dioceses that once had them no longer do."

An undated photo from the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis archives shows a Catholic missionary with Native American youth. On May 9, 2023, a group of archivists, historians, tribal members and other supporters unveiled a list of some 87 Catholic-run Native boarding schools that had operated in 22 U.S. states before 1978. (OSV News/Archdiocesan Archives, Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis)

One example of progress, however, came during this year's annual Child and Youth Protection Catholic Leadership Conference, held in the San Diego Diocese. Maka Black Elk, then-executive director for Truth and Healing at Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, spoke about the church's role in boarding schools for Native children and the need for cultural competency in the church.

"It's a hopeful step and there needs to be much more of that," Rodriguez said.

Maka Black Elk spoke about the church's role in boarding schools for Native children at the 2023 Child and Youth Protection Catholic Leadership Conference in the San Diego Diocese. (CNS/Courtesy of Red Cloud Indian School)

Echoing survivors and other advocates, Hoang, at Siena College, said he'd liked to see bishops publicly acknowledge the impact of abuse on communities of color. He believes it would help victims overcome some shame and stigma and encourage more Black, brown, Asian, Latino and Indigenous survivors to come forward.

But even if most members of the U.S. hierarchy failed to concede the role of race in the abuse crisis, a growing number of survivors of color are learning to find their voice, several advocates said, and dioceses must be better prepared.

If these victims reach out to the church to report abuse and seek help, "I don't want them to be retraumatized," Rodriguez said. "I want their sacred stories honored, not torn to pieces."