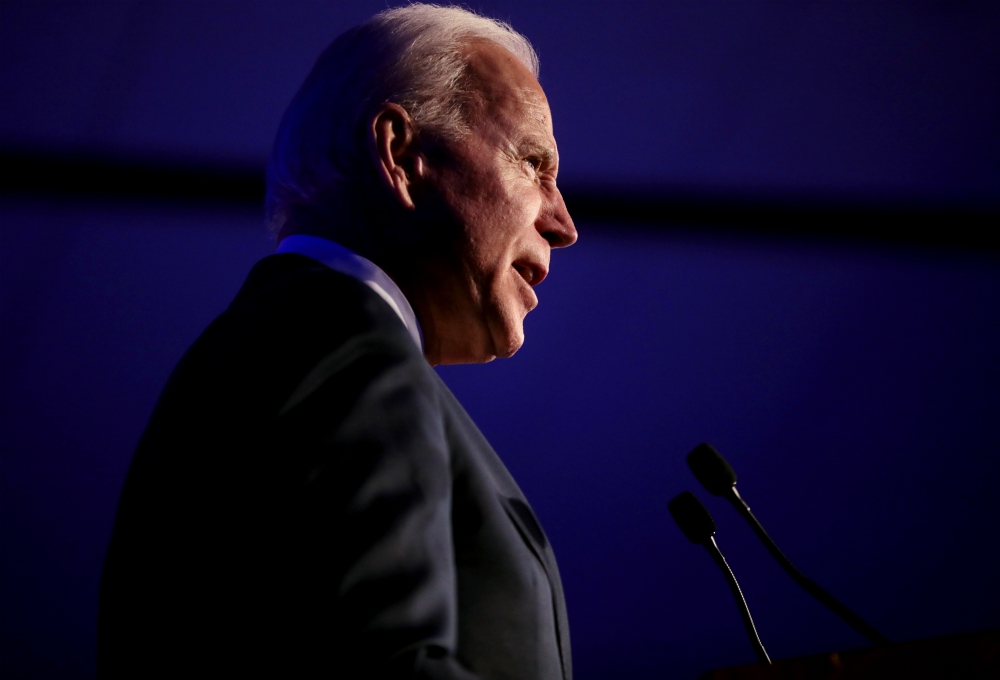

Former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden speaks at a Democratic presidential primary event in Las Vegas Feb. 15. (Wikimedia Commons/Gage Skidmore)

As uprisings sparked by George Floyd's death erupted throughout the nation, Joe Biden turned to his Catholic faith to offer inspiration to a nation gripped by yet another killing of an unarmed Black man at the hands of a white police officer.

"I grew up with Catholic social doctrine, which taught me that faith without works is dead, and you will know us by what we do," he said in a videotaped eulogy June 9, lamenting that there is still much work to be done "to ensure that all men and women are not only created equal, but are treated equally."

Biden reiterated that last phrase when the civil rights hero Congressman John Lewis died July 17. Biden's statement began: "We are made in the image of God."

A "prayer to overcome racism" in a recent church bulletin at St. Joseph on the Brandywine in Greenville, Delaware, offered similar sentiments. The suburban parish north of Wilmington is where Biden and his wife, Jill, worship and where, Msgr. Joseph Rebman told NCR, "they arrive a little late and leave a bit early, just like a lot of Catholics."

Biden's faith is cited on the first page of his 2007 memoir, Promises to Keep, firmly situating himself in the context of an Irish Catholic family and a working-class community that revolved around the family's religious practices — and not just on Sunday.

John Carr, director of Georgetown University's Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life, told NCR, "For an Irish Catholic kid growing up at a time of Vatican II, civil rights and the Vietnam War, there were several paths forward. Some resisted change and clung to old ways, some abandoned roots to embrace change, and some found in faith and family the strength to work for greater justice."

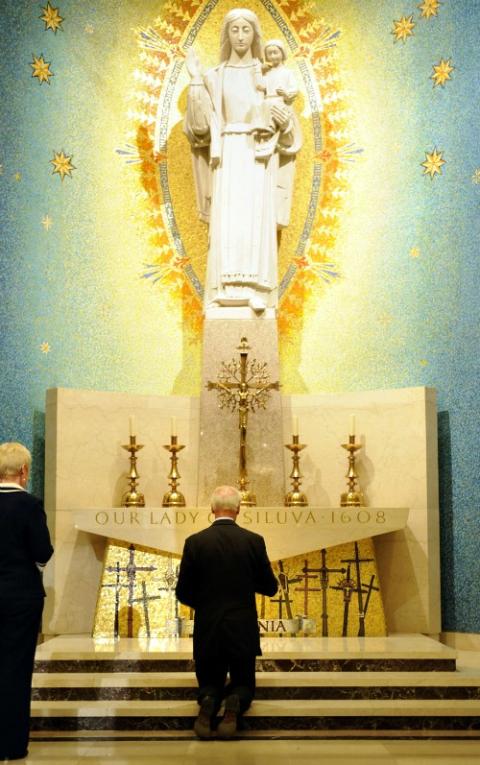

In September 2011, Vice President Joe Biden kneels in the chapel of Our Lady of Siluva at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception following a memorial Mass for Vatican diplomat Archbishop Pietro Sambi in Washington. (CNS/Leslie E. Kossoff)

"Vice President Biden is a unique combination of roots and change," said Carr.

Biden credits those Catholic roots — which first took seed in parishes and parochial schools in Pennsylvania and Delaware — with teaching him the importance of the human dignity of all people, a core principle of Catholic social teaching. They also shaped his understanding of solidarity, especially with the poor and the working class, which he regularly cites when talking about job security and economic policy.

Most importantly, his is also a faith that has been tested by personal loss of an enormous magnitude and one that has come into conflict with Democratic policy positions, forcing him to change and evolve along the way to keep up with shifting uniform stances within the party.

Now, at 77, the former senator and former vice president could be on the cusp of becoming only the second Catholic president in U.S. history. He is hands down the most comfortable Democratic politician of his generation talking about the role religion has played in shaping his approach to public life. As such, John McCarthy, the deputy national political director for the Biden campaign, told NCR that "faith outreach is probably the most integrated it's ever been on a presidential campaign" for a Democratic candidate.

As President Donald Trump's poll numbers continue to decline among people of faith, the Biden campaign is hoping that the authenticity of Biden's personal story, and, in particular, his Catholic faith will offer a stark moral contrast to Trump.

'For the soul of this nation'

In the opening salvo of his campaign last year, Biden declared that America is facing "a battle for the soul of this nation," a line he has used repeatedly. Those close to Biden say it illustrates the inextricable way that his faith informs his approach to public life and is shaping his bid for the presidency.

"In his own mind, it's the inspiration to just about everything the campaign is trying to do," said Stephen Schneck, executive director of the Franciscan Action Network in Washington D.C.

"Biden actually sees his Catholic faith as a key for bringing the country back together and overcoming the divisions that divide us," Schneck said. "He thinks there's something in Catholicism itself that provides a ground where both sides can find commonplace."

In an op-ed last December, Biden summarized part of his pitch to religious voters, saying Trump "doesn't know what it means to live for or believe in something bigger than himself."

Michael Wear, who led President Barack Obama's faith outreach during the 2012 campaign, said that message is central to the distinction that the Biden camp is hoping to offer. "Donald Trump is someone who needs religion to work for him in order to be politically successful," said Wear. "He is someone who has used religion and religious people. He values them to the extent that they're valuable to him."

"The contrast Joe Biden has to offer," Wear continued, is that he "isn't looking to see what faith can do for him. His life has been looking to see how he can serve out of, in part, a motivation of faith."

Biden 'cares about what the bishops have to say, even if he knows he's going to disagree with them.'

—Michael Wear

Such a contrast may not be enough to win over some religious voters who singularly focus on abortion, nor may it appease those who are skeptical of his denials that he sexually assaulted a former Senate staffer.

During a May virtual town hall sponsored by CatholicVote.org, Mick Mulvaney, Trump's former chief of staff and another practicing Catholic, warned, "There is something that doesn't connect any more between faith and the Democrat Party."

Citing abortion, Mulvaney said, "You have to not only vote the Republican Party, but you have to help get them elected."

In an even bolder statement, Fr. Frank Pavone of the organization Priests for Life recently penned an open letter to Biden, urging him to "conform your conduct to the Church to which you claim to belong, or acknowledge that you no longer belong to it."

Over the years, Biden's abortion stance has increasingly liberalized. In a 1974 interview, he said, "I don't like the Supreme Court decision on abortion. I think it went too far."

But as the pro-choice platform became Democratic Party orthodoxy, Biden shifted, too. In a 2012 vice presidential debate with Catholic Republican Congressman Paul Ryan, Biden said, "I accept my church's position on abortion. ... I accept it in my personal life. But I refuse to impose it on equally devout Christians and Muslims and Jews."

This position has evoked the ire of some Catholic bishops and Catholics like Carr who have criticized Biden for falling in line with the "extremism" of the Democratic Party's position on abortion. Schneck told NCR that it's a profound disappointment to see Biden further shift to support federal funding of abortion during the 2020 primaries.

"I disagree with the vice president on this issue, but I don't see this as suggesting he's not a good Catholic," said Schneck, who still believes that voters will have with Biden a president who takes faith and people of faith seriously.

Far from Trump's recent warnings that Biden will "eliminate religion" if elected, "he actually cares what religious leaders think," former George W. Bush speechwriter Michael Gerson said at a Georgetown University forum July 10.

President Barack Obama, Vice President Joe Biden and senior staff react in the Roosevelt Room of the White House as the House passes the health care reform bill March 21, 2010. (Flickr/Obama White House/Pete Souza)

"He cares about what the bishops have to say, even if he knows he's going to disagree with them," said Wear, noting that during the clash between the U.S. bishops and the Obama administration over health care reform, it was Biden who served as a behind-the-scenes liaison trying to accommodate faith leaders' concerns.

Daughter of Charity Sr. Carol Keehan, CEO of the Catholic Health Association from 2005 to 2019, recalls first meeting Biden at a 2009 press conference at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building with key health care reform stakeholders. They became fast friends, she said, noting that they bonded over two major things: frustration at their fellow Catholics who were "being used to create dissent that [the Affordable Care Act] would be the cause of the largest expansion of abortion in the history of our country," and a firm conviction that the health care legislation was a direct response to the church's social teaching to care for the most vulnerable.

"What it really actually did was give people the money to afford their pregnancy and afford the child that would be the fruit of their pregnancy," Keehan told NCR. "It was the strongest pro-life thing we could do."

She added that she and Biden would often have conversations about "what it really meant to be pro-life."

While Keehan became a reliable ally for the administration, estimating that she's either been in the room or at events with Biden "at least 100 times," the country's Catholic bishops ultimately opposed the legislation, arguing that it would provide funding for abortion.

Keehan and the administration disagreed, and the Catholic Health Association, along with a group of nuns representing the overwhelming majority of religious sisters across the country, endorsed the legislation. Both Biden and Obama would later say the law would not have gotten through Congress without the crucial support of the nuns.

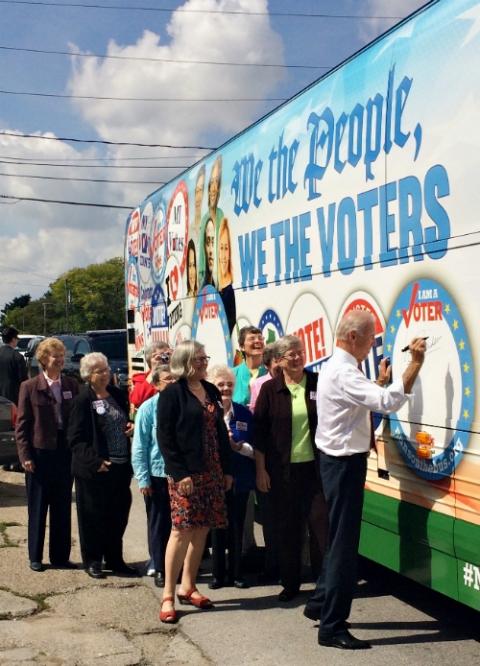

Vice President Joe Biden signs his name to the Network Nuns on the Bus official vehicle on Sept. 17, 2014, after speaking at the kick-off rally in front of the State Capitol in Des Moines, Iowa. Standing behind him is Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell (in red shoes). (GSR file photo/Courtesy of NETWORK)

Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell, the head of the lobbying group Network, who led the effort to get religious sisters to support the legislation, recalls meeting Biden at the White House on the day the Affordable Care Act was signed into law on March 23, 2010.

When she introduced herself to the vice president, she recalls that he "proceeded to have a pastoral visit with me about how much we had nourished his faith."

"Some days, it was so hard and challenging to be dismissed by leaders in the church when he is a man of faith and it really matters to him," Campbell told NCR. "It gave me a window into the pain that our political leaders have when they're made a spectacle of for church politics."

Biden would later join Campbell's Nuns on the Bus tour in 2014, treating a dozen of the sisters to lunch at the Waveland Diner in Des Moines, Iowa, and becoming the first of thousands to sign his name on the side of the bus. When he wanted to ride inside the bus to spend more time with the sisters, Campbell recalled, the Secret Service detail originally said no. "Find a way to make it work," he told them.

'A sense of solace'

In 2008, on the Saturday before Election Day, Biden had a full day of stump speeches planned, but at the last minute squeezed in one more event: Mass for All Saints Day, even though by falling on a Saturday, it was not a holy day of obligation.

"I made 9 o'clock," he went on to tell crowds later that morning. "My mom is 91 years old. I'll call my mom sometime today and the first thing she'll ask is 'Joe, did you go to Mass?' "

Shaun Casey, who would later work in the Obama-Biden administration under Secretary of State John Kerry, recalls being in the crowd that morning in Evansville, Indiana. "It just came naturally to him," Casey told NCR. "He didn't study his way into the Catholic Church in graduate school. It's been a constant through his life."

Biden's Catholic family and schooling, he writes in his memoir Promises to Keep, provided him with a portrait of the "sort of man I wanted to become."

"Wherever there were nuns, there was home," Biden writes, fondly recalling the Sisters of St. Joseph, who taught him invaluable lessons at Holy Rosary in Claymont, Delaware.

One day, a student threw an eraser while Sister Michael Mary was out of the classroom. When she returned, the sister said no one could leave until the responsible student owned up to their actions. Young Joe Biden raised his hand, allowing the students to go home.

Sister Michael Mary told him, "You admitted to doing something you didn't do. It's admirable, but you still have to pay for it."

The moral of the story, he writes in Promises to Keep, is one that's never left him in public life: "When you intervene, you have to stand up and take the consequences."

Advertisement

After serving as county councilman, Biden successfully entered national politics in 1972. At 29, he became the youngest senator-elect in the country.

The joy of that unlikely victory, however, was shattered when just five weeks later, his wife, Neilia, and their 1-year-old daughter, Naomi, were killed when a tractor trailer hit their vehicle en route home from Christmas shopping.

The Biden's two sons, Hunter and Beau, were severely injured but survived, leaving him a single father and giving the promising young senator his first experience with incredible loss while in the public eye.

It would happen again, when Biden's eldest son, Beau, died of brain cancer in 2015 at the age of 46.

For thousands of people across the United States, Biden's public experience of grief has proved to be a point of connection, often mirroring tragedies in their own life, and a chance to empathize over this most basic of human experiences.

When Biden appeared on Stephen Colbert's "Late Show" a few months after Beau's death, the two Catholic men bonded over their shared experiences of suffering and reconciling loss with faith.

"My religion is just an enormous sense of solace," Biden told the late night host, who had lost his own father and two brothers at a young age. "What my faith has done is it sort of takes everything about my life with my parents and my siblings and all the comforting things and all the good things that have happened, have happened around the culture of my religion and the theology of my religion, and I don't know how to explain it more than that."

Carr from Georgetown recalled the scene: "It was like two Catholic guys in the parking lot after Mass talking about their loss. It's who they are."

President Barack Obama hugs Vice President Joe Biden after delivering a eulogy during the funeral Mass for Beau Biden at St. Anthony of Padua Catholic Church in Wilmington, Delaware, June 6, 2015. (Flickr/Obama White House/Pete Souza)

When Biden asked Jesuit Fr. Leo O'Donovan, former president of Georgetown, to be the principal celebrant and homilist at Beau's funeral, the priest's first words to Biden were, "Joe, I am so sorry," before he himself erupted into tears.

"He began to comfort me," O'Donovan said. "He became the pastor there."

O'Donovan believes that despite the understandable questioning of why God could allow such tragedies to happen, Biden has taken solace in the belief that suffering is eventually overcome by resurrection and new life.

Yet Biden has also admitted that at times his faith seemed distant or ephemeral. In 1992, O'Donovan invited Biden to speak at Georgetown, where Hunter was a senior. Biden told the priest it was the "toughest assignment he's ever had."

"I'd never talked about my faith publicly. I mean, I acknowledge that I'm a practicing Catholic, but I don't think it's anybody's business, nor do I think it should matter to anyone," Biden would later recall in discussing the address.

The speech was hardly theological in nature, focusing more on the morals instilled in him through his Catholic upbringing rather than the complexities of integrating church teaching into public policy.

"Those corny middle-class values have had a very practical implication," he told the 500 students gathered in Georgetown's Gaston Hall, adding that he learned that government could serve as a means to fight the injustices that his faith taught him to work to overcome.

O'Donovan admits Biden is not a theologian. But the Jesuit is "absolutely convinced" that Biden is "a profoundly faithful and believing Catholic."

"I'm not sure how much he's even aware of how much it embodies the Second Vatican Council," O'Donovan continued, "but Gaudium et Spes speaks of the birth of a new humanism where people are defined by their responsibilities to their brothers and sisters and to history. That's Joe Biden."

Public policy and the pope

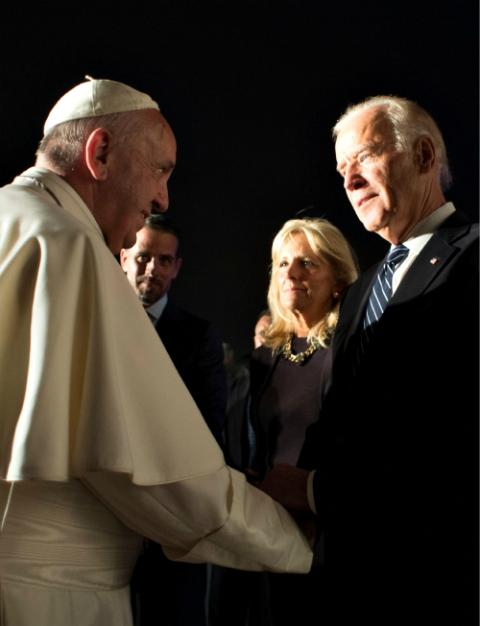

Just four months after Beau's death, Biden received a pastoral visit from Pope Francis, who met with the extended family in the airport hangar before returning to Rome after his six-day visit to the United States in September 2015.

"I wish every grieving parent, brother, sister, mother, father would have the benefit of his words, his prayer, his presence," Biden said afterward. "He provided us with more comfort than even he, I think, will ever understand."

Pope Francis greets Vice President Joe Biden and his wife, Jill, during a farewell ceremony at Philadelphia International Airport Sept. 27, 2015. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano, handout)

As host to Francis during the visit, Biden's Catholic faith was constantly in the public spotlight.

"It was deeply special and moving to him to be there at the center of his church and doing something important," said Ken Hackett, who served as U.S. ambassador to the Vatican during Obama's second term and worked closely with Biden, both in Washington and during trips to Rome.

Biden felt that he really had something to offer the leaders of his church, Hackett told NCR.

In the lead-up to Francis' visit, Biden hosted a series of breakfast meetings at his residence with Catholic leaders in Washington, not to discuss the logistics of the visit itself but how it might serve as a unifying occasion.

"He wanted to make sure everyone could hear the pope's message without it getting hijacked," recalls Franciscan Action Network's Schneck, who at the time led the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies at the Catholic University of America and was a participant in those gatherings.

"He was very concerned that it wouldn't cause the usual left/right divisions in American politics but that it would be a unifying moment," he said.

Melissa Rogers, who was then executive director of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships, told NCR that ahead of the visit, Biden also met with religious and civil society leaders to solicit their support on practical ways they could punctuate the pope's visit with policy initiatives reflecting common ground between the White House and the Holy See.

Those meetings resulted in a series of executive actions to increase refugee admissions to the U.S. and efforts to combat climate change, which Rogers said is "an example of how Vice President Biden understands the positive roles that people of faith can play in public life."

Denis McDonough, who served as the White House Chief of Staff from 2013 to 2017 and is himself a practicing Catholic with two brothers in the priesthood, told NCR, "The president really leaned on the vice president in terms of understanding the Holy Father, his personal history and how he had been shaping his papacy."

Joe Biden, then vice president-elect, holds his grandson Hunter Biden and shakes hands with Jesuit Fr. Mark Horak following Mass at Holy Trinity Church in Washington Jan. 18, 2009. (CNS/Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

Further, McDonough said, it was an important priority for Obama to have a strong relationship with the Holy See, which he said was ultimately a success in large part due to the work of Biden. McDonough noted that the administration worked closely with Francis on a number of projects, including opening up relations with Cuba and rallying support for the Paris climate agreement.

McDonough also recalls other witnesses to Biden's faith. While in the Situation Room during the 2011 special ops operation that resulted in killing Osama bin Laden, McDonough remembers seeing Biden and Admiral Mike Mullen clutching their rosary beads while watching the attack play out.

"The vice president always had his beads or his pocket rosary, and I remember seeing him praying with that on a lot of different times," he told NCR.

Four years later, after a gunman killed nine churchgoers at a historic African American church in Charleston, South Carolina, Biden would take out his rosary beads and show them to a grieving congregation as a sign of solidarity, both of faith and loss. During this year's Democratic primaries, that same base of Black South Carolina churchgoers would prove critical in delivering him a much-needed win that would propel him as the frontrunner in the presidential primary contest.

For McDonough, that is further proof that people see his authenticity as intricately linked to his faith.

"It's one of the things that strikes me about the grounded nature of the vice president. He's never far from prayer, which is a sign of an empathetic leader."

Second Catholic president?

The election of a first Catholic president 60 years ago sent shockwaves through a once staunchly Protestant nation. Yet when the Earl of Longford remarked to Kennedy's younger sister, Eunice Shriver, that a book should be written about President John F. Kennedy and his faith, she said, "It will be an awfully slim volume."

For Biden, by contrast, the Irish Catholic faith of his youth seems to be written on nearly every page of his long life in an indelible way that has shaped his full biography. It is not one of window dressing; it is the window through which he sees much of his public life.

New York University professor and Kennedy scholar Timothy Naftali told NCR, "Kennedy didn't share his inner spiritual life with the public. He left it mysterious and downplayed its effect on his approach to leadership. He did speak of the moral force of the presidency, but, perhaps because of the pervasive bigotry toward Roman Catholics at that time in U.S. history, he left unspoken the sources of his understanding of moral imperatives."

"Biden, while clearly a fan of Kennedy's, emerged in an era where Catholic politicians didn't need to be as circumspect," noted Naftali. "He wears his faith on his sleeve and proudly explains the effect of his upbringing on his worldview."

'When you're trying to reach faith voters, it's all about authenticity.'

—Biden campaign staffer John McCarthy

Biden began college the fall after Kennedy was sworn in. Kennedy confronted the prejudices that Catholics couldn't hold the highest office in the land, telling an audience, "I refuse to believe that I was denied the right to be president the day I was baptized." Biden took this as inspiration that he could do the same.

Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne told NCR that "the way Biden looks at the world is very much influenced by the era of 'the two Johns,'" a phrase that the writer Garry Wills used to describe the time in which Kennedy was in the White House and Pope John XXIII was reigning in Rome.

"It was a time when Catholics were finally finding their place in American politics and obviously had an enormous pride in Kennedy's election, and if you were a Democrat, as most Catholics were at the time, you found real comfort in John XXIII's attitudes toward social justice and peace," said Dionne.

Pope John had staked his papacy on the notion that the church should be open to the modern world, and in particular, serve as a force for peace in it. His seminal 1963 encyclical, Pacem in Terris ("Peace on Earth"), was addressed not just to Catholics but to all people of goodwill, inspiring nations and individuals to embark on peacebuilding.

"For a mainstream moderate liberal like Joe Biden, those are the way in which he understood Catholicism's social demands," Dionne said.

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden talks with local residents about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on their small businesses, on the outside patio of the Carlette's Hideaway sports bar during a campaign stop in Yeadon, Pennsylvania, on June 17. (CNS/Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

As the Biden campaign heads into November, it is attempting to offer a contrast of two candidates with radically different understandings of faith: Politics, for Biden, serves as a means of living out a vocation, not a vanity project. Instead of only showing up at houses of worship for a photo op, Biden rearranges his schedule to ensure he doesn't miss a holy day of obligation. Rather than achieving national fame for taking pride in telling individuals, "You're fired," one of Biden's most frequent refrains has been about the dignity of work. Instead of pointing to bestselling books or buildings on Fifth Avenue as chief accomplishments, Biden calls the 2016 decision by the University of Notre Dame to award him with the Laetare Medal, the highest prize in American Catholic life, as the most meaningful honor of his lifetime.

"The best thing we have on our side is the vice president being who he is," campaign staffer McCarthy told NCR, adding, "When you're trying to reach faith voters, it's all about authenticity."

That authenticity traces its past back to Scranton, Pennsylvania, in what longtime Democratic strategist Donna Brazile told NCR is an Irish Catholic faith of "grit and spirit" with undeniable "strong Christian roots" that she says won't be put away in the Oval Office.

And for Biden's allies, his closing argument to people of faith comes down to that: You can't reclaim the soul of a nation without first taking seriously the state of your own.

[Christopher White is NCR national correspondent. His email address is cwhite@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @CWWhite212.]