(Dreamstime/Syda Productions)

"I was scared I was going to die every time I was pregnant," said Laurie Bertram Roberts, a 44-year-old mother of eight who lives in Mississippi.

Roberts is not alone. For many Black women in the United States, the prospect of childbirth comes with fear.

"It should be one of the most joyous times — the whole birth process or thinking of creating or expanding their family — but they have to think about dying," said Dr. Rachel Villanueva, an OB-GYN and president of the National Medical Association, the leading Black medical society. "You try to comfort and reassure them, but all they have to do is look at the statistics. The statistics are horrifying."

A 2021 report by the Commonwealth Fund indicates Black mothers are more than twice as likely as white mothers to experience severe pregnancy-related disease or illness. African American women from all walks of life and income levels are also dying from preventable pregnancy-related complications at nearly three times the rate of non-Hispanic white women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Villanueva said this is even more alarming given the United States has the highest maternal mortality rate among developed countries.

In many states, Black women are more likely than white women to give birth at a Catholic facility, and nationwide one in seven patients is cared for within a Catholic hospital.

Given its reach, and foremost because of its mission to carry on Jesus' ministry of love and healing for all people, "Catholic health care has an important role to play in working to eliminate disparities in maternal outcomes," said Sue Kendig, a women's health integration specialist at SSM Health St. Mary's Hospital in St. Louis. Kendig holds several appointments to national health-related policy efforts.

While Catholic health care leaders have launched ambitious initiatives to reduce inequities, some researchers, reproductive rights advocates and Black women, including Roberts, suggest Black women are being disproportionately harmed by the religious directives that inform Catholic-based care.

'I almost died'

At 12 weeks into one of her first pregnancies, Roberts began bleeding and went to a nearby Catholic hospital's emergency room, worried she was having a miscarriage.

"I was told, 'We don't think you are miscarrying, but go home, put your legs up and come back if the bleeding increases,'" Roberts told NCR. The next day she was bleeding heavily and in intense pain, so she returned.

Laurie Bertram Roberts, a doula, prominent reproductive rights advocate and "aspiring midwife" (Courtesy of Laurie Bertram Roberts)

"They did an ultrasound, and the doctor said I was having a miscarriage — the embryo had stopped progressing around week six — but there was nothing they could do because there was still a heartbeat. I was told that if I was hemorrhaging, I should come back."

At home again, she tried to tough out the pain and bleeding. Eventually, she fainted. "I remember feeling like I was in a tunnel," said Roberts. "I could hear people's voices but couldn't respond."

Transported to the hospital a third time by ambulance, Roberts needed to have a blood transfusion. "I almost died," she said.

Unable to detect a fetal heartbeat, the hospital then provided treatment for the miscarriage.

"I just wanted to live and get home to be with my other babies," said Roberts. "I was young, low-income, trying to navigate life and survive. I didn't have time to pause and understand the profound trauma until later."

Roberts said the experience was not only another example of "Black women's pain being dismissed"; she believes it also underscores how the interpretation and implementation of religious directives at Catholic facilities exacerbate inequity.

Catholic hospitals in the United States are guided by the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, a set of 77 points developed by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. For years, national medical associations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have claimed the directives harm women by prohibiting the use of sterilization for contraceptive purposes, abortions and a number of fertility treatments.

Catholic directives and women of color

"Bearing Faith: The Limits of Catholic Health Care for Women of Color," a report published in 2018 by the Law, Rights, and Religion Project at Columbia Law School, links the directives with racial disparities in health care while also asserting treatments for miscarriages and extrauterine pregnancies are of particular concern under the directives.

Elizabeth Reiner Platt, co-author of "Bearing Faith: The Limits of Catholic Health Care for Women of Color" (Courtesy of Elizabeth Reiner Platt)

It found in many states Black women are more likely than white women to access Catholic health care institutions. Because of this, the authors argue, Black women disproportionally bear the harmful repercussions of certain directives.

The report says that the directives are interpreted or enforced in a range of ways, but that to avoid abortion procedures, some providers have not adequately treated women who were miscarrying or experiencing ectopic pregnancies — when a fertilized egg implants outside of the uterus.

"According to at least one provider at a Catholic hospital, such refusals have led to tubal rupture," reads the report.

A recent study funded by the National Institutes of Health notes ectopic pregnancy is the fifth leading cause of maternal death for Black women. It is not among the leading causes for white or Hispanic women.

"Bearing Faith" also says some Black women, like Roberts, reported being sent home from emergency rooms with heavy bleeding while miscarrying.

Roberts said the potentially significant harm the ethical directives can cause should be part of any discussion around maternal health equity at Catholic hospitals. "This is not an isolated incident; similar stories have happened around the country," she said. "It's time for the church to understand the pain and trauma they are causing, especially to marginalized women."

Roberts said that during her miscarriage she was never informed about the directives.

'I just wanted to live and get home to be with my other babies. I was young, low-income, trying to navigate life and survive. I didn't have time to pause and understand the profound trauma until later.'

—Laurie Bertram Roberts

A 2019 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found a majority of U.S. Catholic hospitals do not disclose on their websites that they have religious policies limiting the types of reproductive services offered.

At a minimum, Roberts said, "patients should have the right to know they exist."

Elizabeth Reiner Platt, director of the Law, Rights, and Religion Project and co-author of "Bearing Faith," said she would like the church and people in the pro-life movement "to at least honestly acknowledge" that they think experiences like Roberts' "are an acceptable consequence of banning abortion."

Platt stressed the report is not intended to make any correlation between maternal mortality and the rates of Catholic hospital usage. But given Black women already receive unequal treatment in care, "it's all the more troubling that they are going to hospitals where a high standard of care is not always being met."

Cumulative trauma

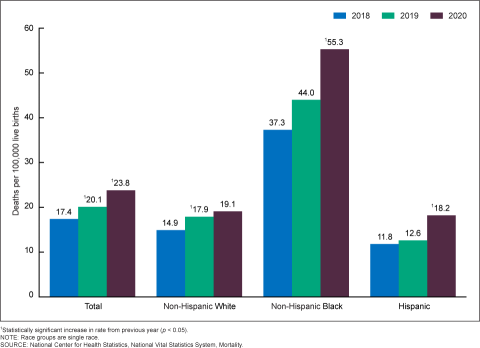

A report this February from the National Center for Health Statistics found the maternal mortality rate for Black women jumped 26% in 2020, the first full year of the coronavirus pandemic, while the increase for white women was "not significant."

The pandemic "certainly highlighted what we already knew: We have not done a good job and we are not doing a good job of achieving health equity," Villanueva said.

Dr. Rachel Villanueva, president of the National Medical Association, the leading Black medical society (Courtesy of Rachel Villanueva)

In a process called "weathering," the cumulative trauma of political marginalization, racism and discrimination corrodes health and likely places Black pregnant women at a higher risk for a range of medical conditions. Research also shows racism and unconscious bias persist in the U.S. health care system itself and can cause unequal treatment for women of color.

Villanueva said Black patients often don't feel heard by their doctors, and their complaints of pain or symptoms are dismissed.

Roberts, now a doula, prominent reproductive rights advocate and "aspiring midwife," said there were times when she had serious pregnancy-related concerns "and doctors basically blew me off."

"Like when I was throwing up water and losing weight, and the doctor said, 'Oh, you'll be OK,' " she recalled. "It happens to Black women all the time — our pain is diminished; our concerns are minimized."

When it comes to maternal health and mortality rates, income level and education status do not protect Black women as they do white women.

"I think we get comforted that maybe this happens only to people who are poor, who don't have access to resources, who are making decisions that don't support health," said Kendig. "But that's not what's happening."

Racism confronted

Over the past several years, Catholic health care systems across the country have attempted to improve health equity. They've formed partnerships, pushed for legislation and focused on social and structural determinants of health.

In 2021, the Catholic Health Association of the United States launched "Confronting Racism by Achieving Health Equity," which includes support for Black pregnant women and new mothers.

Advertisement

The association has lobbied to extend Medicaid coverage to a year after pregnancy and for the passage of the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, a legislative package of 12 bills originally included in the now-defunct Build Back Better Plan. One of the bills, supporting pregnant and postpartum veterans, has since been signed into law, and both Kendig and Villanueva feel hopeful others eventually will be enacted. The bills include such measures as developing technology that improves health outcomes, and grants that address pregnancy-related risks associated with climate change.

Catholic Health Association is focused on building trust within Black communities, "working with them to identify needs, listening and making sure the needs are being met," said Kathy Curran, senior director of public policy for the association.

The world's largest Catholic health system, Ascension, is participating in a national effort launched by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to improve maternal health equity. And CommonSpirit Health has partnered with the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta*, one of a handful of historically Black medical schools in the country, to recruit and train more Black doctors. (Xavier University of Louisiana, the nation's only Catholic historically Black university, recently announced plans to establish a medical school.)

Sue Kendig, a women's health integration specialist at SSM Health St. Mary's Hospital in St. Louis (Courtesy of Sue Kendig)

SSM Health, which includes hospitals across the Midwest, is involved with the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health and its national quality improvement effort. The alliance enables health care teams to practice their response to emergencies.

Woven into care, said Kendig, is a commitment to "radical listening, understanding there may have been traumas influencing a particular moment and knowing implicit and explicit biases exist."

In a notable example of success, Providence Health & Services and its family of organizations across seven states have nearly eliminated preventable birthing deaths since 2017, according to Whitney Haggerson, Providence vice president of health equity and Medicaid. Providence also is building upon existing doula programs to better support birthing patients of color.

Catholic health care leaders also have responded to criticisms about the directives, maintaining that they reflect the belief that all life is sacred while also allowing for the treatment of life-threating complications in pregnancy.

Mercy Sr. Mary Haddad, Catholic Health Association's president and chief executive, wrote a letter to The New York Times in March objecting to a recent article's critique of how Catholic hospitals care for pregnant women.

"Catholic hospitals follow established clinical protocols when a fetus cannot come to term and could cause infection or even death for the mother," she wrote. "The removal of a diseased part of the fallopian tube in an ectopic pregnancy or treatment of a uterine infection are both clinically and ethically required."

Nate Hibner, director of ethics for Catholic Health Association (Courtesy of Catholic Health Association)

Nate Hibner, director of ethics for Catholic Health Association, told NCR one of the challenges in the medical world is that words like "abortion" and "termination" may be medically similar but morally "totally different." He believes the directives are misunderstood by people on both sides of the political aisle, "who make the assumption that they are a legalistic rule book."

"It's more an aspirational document that addresses the values and commitments from our faith."

Most of the directives are positive statements that emphasize "care for the common good and our obligation to the poor and vulnerable," explained Hibner.

Directive No. 3 states: "Catholic health care should distinguish itself by service to and advocacy for those people whose social condition puts them at the margins of our society," including the poor, the unborn, those with incurable diseases and chemical dependencies, immigrants, and racial minorities.

"Catholic health care is more than just a provider of medical treatments or medical services," said Hibner. "We see ourselves as a ministry that draws upon the church's long tradition of social justice."

Efforts to improve Black maternal health, he added, is work compelled by "our rich Catholic tradition and Catholic teaching."

*Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly described the relationship between the Catholic Health Association and Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta. We apologize for the error.