Lego "Star Wars" minifigures Luke Skywalker and R2-D2 are pictured. In the film "Star Wars," Luke receives a lightsaber at Obi-Wan Kenobi's hut on the planet Tatooine. Author Eric Clayton reflects on building a Lego set of Obi-Wan's hut with his daughter. (Unsplash/Studbee)

Last summer, I receive a gift: a new "Star Wars" Lego set.

It arrives in an unassuming brown box on my front porch during my daughters' nap time. I open and deposit its contents of colorful plastic bricks on our kitchen table, knowing how excited my 3-year-old will be when she wakes up.

"Can we build that tonight, Daddy?" she asks, as we walk to the grocery store. We need more milk.

I've spent not an inconsequential amount of time during the pandemic introducing her to "Star Wars" and Lego. Her fingers still lack the dexterity needed to navigate the tinier pieces, but she is persistent. She gets excited at the prospect of new minifigure characters, even if she has no idea who they are or what role they play.

I bite my lip, mulling my response, torn between a father-daughter experience and that temptation to play with my toys in peace.

"I think so," I say, finally, just as excited as she is — if not a bit more.

Random Lego pieces (Unsplash/Xavi Cabrera)

The set depicts Obi-Wan Kenobi's hut on Tatooine, and, more specifically, the moment in which R2-D2 reveals to the old Jedi Knight Princess Leia's secret message. It's a classic, pivotal scene.

Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi. You're my only hope.

It's a spiritual experience, entering into such a crucial cinematic moment. To play a role in how the scene is constructed. To place one piece after another and see manifested in my hands what was previously confined to my imagination — and the picture on the box.

So much hinges on this moment, fiction though it is. Without those fateful words — Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi — would the story of "Star Wars" have taken place? Would the galaxy have been saved? Or would all be lost to darkness?

Moments of existential consequence aren't limited to space operas and the silver screen. We celebrate and commemorate and participate in such moments in our faith lives. We spill the little pieces of our spiritual selves across the floor and endeavor to assemble them in a meaningful way. We imagine ourselves playing a role in these moments.

Lent has been our exercise in assessing the pieces, holding each up, examining it, placing it just so. And when Easter arrives, we catch a glimpse of how those seemingly random little plastic bricks are transformed into something spectacular. Something essential. Something pivotal.

Our own participation in the Easter story. But we don't participate alone.

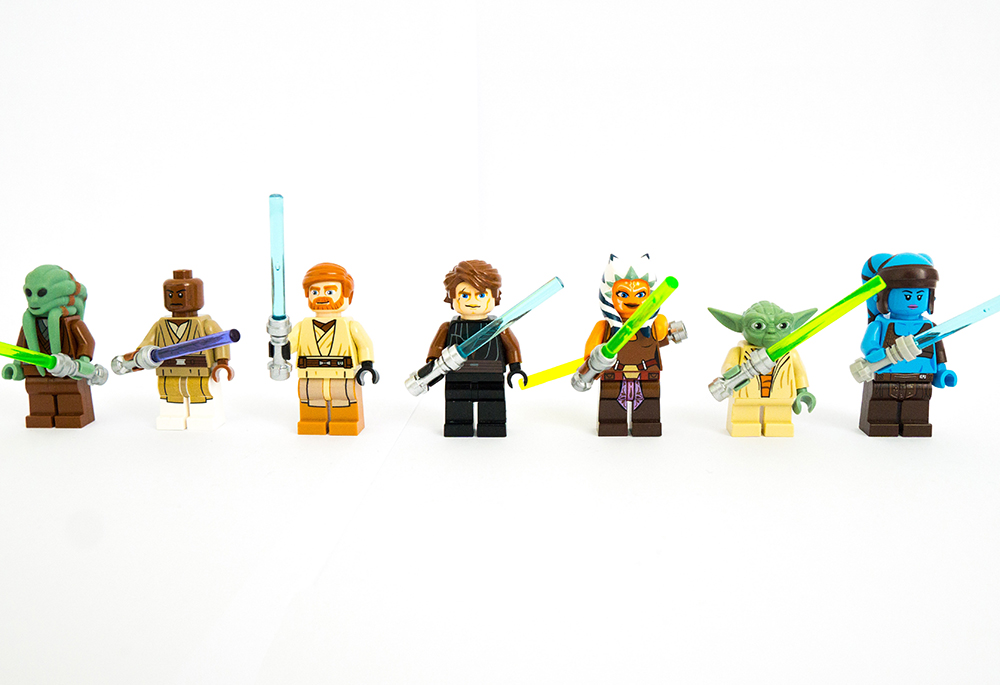

Lego "Star Wars" minifigures are pictured, including (from left) Kit Fisto; Mace Windu; Obi-Wan Kenobi; Anakin Skywalker; Ahsoka Tano; Yoda; and Aayla Secura. (Unsplash/Eric & Niklas)

My daughter and I begin the Lego build just before dinner, her younger sister distracted by pre-dinner snacks. We assemble old Ben Kenobi and a Tusken Raider and my daughter is immediately excited to find that the set includes a treasure chest.

"What goes in here?" she asks.

"His lightsaber?" I reply, my focus divided between the instruction manual and the myriad tiny pieces now scattered across our floor. We do have a time limit, after all — this needs to be done before the one-year-old is let loose.

"I like this lightsaber," she says, before promptly getting a piece stuck in the tiny treasure chest.

"That doesn't go there," I growl, glaring at the pieces she holds in her outstretched hand. "You have to follow the instructions."

I jam my clumsy finger into the tiny plastic box, unsuccessful in extracting the offending piece. I sigh, audibly, and mutter something about needing a screwdriver. My daughter gets up, runs to her mother.

"Daddy hurt my feelings," she cries.

(Unsplash/Nathan Dumlao)

We take a break. I weigh the possibility of finishing the set after both girls are in bed.

First Corinthians 13:11 comes to mind in moments like these:

When I was a child, I used to talk as a child, think as a child, reason as a child; when I became a man, I put aside childish things.

I wonder if our Lenten journey has revealed those pieces of ourselves that need a little more attention, a little more care, those pieces that might need to be examined and placed in a new way, a new light. Those pieces — those habits and behaviors — that might need the transforming power of the Resurrection.

I think of those behaviors that earn my own children a raised eyebrow and stern voice: outbursts of anger, selfishness and exasperated sighs. Those actions that lead to schoolyard bullying and kids picked last for the kickball team. Those bad habits that snowball into conflict and violence and hatred.

How childish of me to overreact to a silly mistake made by my very eager daughter. I put that aside, as St. Paul suggests.

"I'm sorry that I hurt your feelings," I say over dinner. I want her to know a world where it's OK to apologize, to ask for forgiveness.

"Don't do it again, Daddy," she says, and I nod.

"I'll try," I say.

Do or do not. There is no try, I think. More "Star Wars" — that famous bit of wisdom from Yoda.

I correct myself: "I won't."

Lego "Star Wars" minifigures of droids R2-D2 and D-0 inside a Lego model of the Millennium Falcon ship. (Unsplash/Kristine Tumanyan)

It's the job of a parent to help children envision what life should be like, how society should function. What should be deemed important and essential and valuable. How we should treat one another. To expand the young imagination beyond the immediate, the familiar. To imagine something more, something better — and to set a course for that as-yet-unrealized future.

I decide I can't finish that Lego set alone.

With the 1-year-old in bed and my 3-year-old now in her "Frozen" purple nightgown — teeth brushed, prayers said — we return to our project. I pop that rogue piece out of the treasure chest with a small screwdriver and hand both pieces back to my daughter.

Obi-Wan's hut is coming along well. I marvel at the details: the little blue milk carton, the spare gaderffii, the training droid. As I assemble each, I'm pulled more deeply into that scene, into Kenobi's hut, into the heat of Tatooine, the sand, the twin suns, into the moment when Luke discovers that there's more to his world than he ever imagined.

He just needed someone to invite him in, to show him what was possible. To hold his own spiritual pieces up to the light and suggest something new.

"What about this piece, Daddy?" My daughter is holding up a little blue figurine, translucent and vaguely human-shaped. It's meant to be Princess Leia's holographic form, that pivotal message that sets the events of the original "Star Wars" film in motion.

I realize, then, that my daughter has no real understanding of what it is we are building, what that piece represents. She hasn't seen any of the "Star Wars" movies — just a handful of the cartoons, disjointed scenes and random character arcs.

For her, the scene begins and ends with those little plastic pieces. She has no idea that there is more.

Advertisement

The line that immediately follows the one on childish things in First Corinthians goes like this:

At present we see indistinctly, as in a mirror, but then face to face. At present I know partially; then I shall know fully, as I am fully known.

And so, we complete our building and I pull up the scene we've constructed on YouTube, a variant on a bedtime story. And my daughter and I sit and watch Luke come to glimpse something of the wider universe — and his place within it. The possibility. The Force.

"But they're not Lego," she says, stunned. Her eyes are glued to that tiny screen.

"No," I say. "This is the real thing. This is what we were building."

Don't lose sight of what it is you're building, the Spirit whispers. Don't lose sight of the real people at hand.

Certainly, throughout Scripture, we see Jesus grow frustrated. The disciples just don't get it; they ask impertinent questions. They get Lego pieces stuck where they don't belong. I'm sure Jesus threw his hands up more than once.

But Jesus doesn't finish the work without us; Jesus brings us along. He helps us put those pieces in place and then be about God's work. The stone is rolled away; the resurrected Christ appears to his friends, to us — even if we missed his meaning on more than one occasion, misplaced a piece or two. He reminds us again and again what God's dream for the world actually is, and the unique, invaluable part we play in bringing it about.

We glimpse it, though indistinctly, as in a mirror. And we fumble to snap the pieces in place.