(Dreamstime/Alla Simacheva)

The week of Little Mermaid Dance Camp was hot and unnecessarily humid. A just punishment, perhaps, for the sin of introducing our 3-year-old daughter to a story that encourages young women to trade their voice for a pair of legs in the singular pursuit of winning over a stranger they happened to see at a distance one day.

Or true love, I guess.

But Ariel is a mermaid and a princess, and there was just no way we were going to keep our daughter in the dark about such a winning combination.

"We haven't watched 'The Little Mermaid,' " she would say, slyly, those brown eyes bouncing from me to my wife to the television and back to her Disney princess book. "When can we?"

We eventually ran out of reasons why she couldn't watch it. So, we provided caveats.

"Why did you stop it?" my daughter would complain, her head of curly hair whipping around in accusation at my wife's trigger-happy remote-wielding hand.

"I want to talk about this scene," my wife would reply, assuming the persona of a wizened old teacher. "Now, obviously, you never actually should give up your ability to talk …"

Cue the 3-year-old eye roll.

The compromise was that our daughter could watch the film if she could tolerate my wife's interruptive disclaimers.

Stories are precious, powerful things. They shape our understanding of the world and our place within it. They erect — or, demolish — boundaries in our lives.

That's how "The Little Mermaid" toppled "Tangled" from the No. 1 spot of Disney princess movies.

And why our daughter wound up at Little Mermaid Dance Camp — perhaps she'd discover there was more to the story than an outdated understanding of "true love" and those things we're willing to do in its name.

I took a course called "Fairy Tales" in college. My family rolled their eyes. "How much you paying for that?"

But I was excited. Understanding fairy tales only deepens and expands my love for speculative fiction.

It's not just the escape the genre can provide from life's grueling nonfiction plots. It's the contemplative interrogation of those real and pressing concerns of our real and present day-to-day that provide the willing reader new insight and understanding.

Neil Gaiman, I think, says it best in his paraphrasing of G.K. Chesterton: "Fairy tales are more than true — not because they tell us dragons exist, but because they tell us dragons can be beaten."

It's a genre that helps us imagine the limitless potential of the human person.

(Dreamstime/Lisitsaimage)

Fairy tales, though, live in a literary realm unhindered by continuity and canon — something almost anathema to my love of world-building.

Just look at "Star Wars" and Disney's painstaking efforts to ensure a continuous story across movies, TV shows, books, comics and more. What happens in one story matters to the whole story. To the canon.

Fairy tales, "to the contrary ... circulate in multiple versions, reconfigured by each telling to form kaleidoscopic variations with distinctly different effects," says the introduction of The Classic Fairy Tales. "Local color often affects the premises of a tale."

Can you imagine a franchise that got rebooted literally every time the story was told?

"We found a new version!" my 3-year-old exclaimed, running down the steps to my basement office. "A new version, Dad!" She was just back from their most recent library excursion and brandishing a colorful board book.

"A new version?" I stammered. "Of what?"

"Tangled! But it doesn't have Eugene." She began to furiously page through the small volume.

"Rapunzel," my wife said, stepping into the office, our 1-year-old on her hip. "We found a series of fairy tales that put the stories in different cultures." Then, to our daughter: "Show Daddy the art."

(Unsplash/Zain Saleem)

It was true: Rapunzel, the prince, scene after scene — they all had a distinctly South Asian feel to them. Cinderella — the other book they'd discovered — was Mexican, and the whole book had a Día de Los Muertos design.

"That's so cool," I said. "Reminds me of ..."

"That course you took in college," my wife finished. "I thought it might. I knew you'd like these."

"But there's no Eugene," my daughter pressed. Eugene — or Flynn Rider — is the male protagonist in Disney's "Tangled." He's a compelling character, but decidedly American in his outlook on life.

"This is a different version," my wife insisted.

"It's a different way of telling the story," I continued. "It's still Rapunzel, but ... different."

That's the best I could come up with for a 3-year-old.

Stories are precious, powerful things. They shape our understanding of the world and our place within it. They erect — or, demolish — boundaries in our lives. And, they often stand in as answers to complex questions as parables, fables, myths.

The teller of the story, then, has tremendous power. They select who appears within the story's pages — and who remains absent. In so doing, they provide answers, they ask new questions, and they enforce silence.

Religion is built upon stories. That's why Jesus told parables — he knew that stories could be the answers to those complex questions.

Our world can grow — or grow claustrophobic — at the storyteller's command.

The late author, sociologist and Catholic priest Fr. Andrew Greeley wrote a book titled The Catholic Imagination. I read it around the same time I took that course on fairy tales. And while I can't say how well his arguments hold up all these years later, I can say that one core idea from that book has stayed with me: For Catholics, the stories are in the walls.

Religion is built upon stories. That's why Jesus told parables — he knew that stories could be the answers to those complex questions. Stories help us understand and make sense of faith and doubt, certainty and paradox. Stories help us live in that creative tension that our spiritual lives often demand.

To enter a Catholic Church is to enter a place of storytelling: The statues, the stained glass, the reliquary, the art, even the poor box tell stories. They reflect who we are, who we might yet become. They explore past efforts to grapple with the mysteries of the divine.

But do these stories in the walls represent the gathered faithful, or are we haunted by blue-eyed, white-skinned European saints?

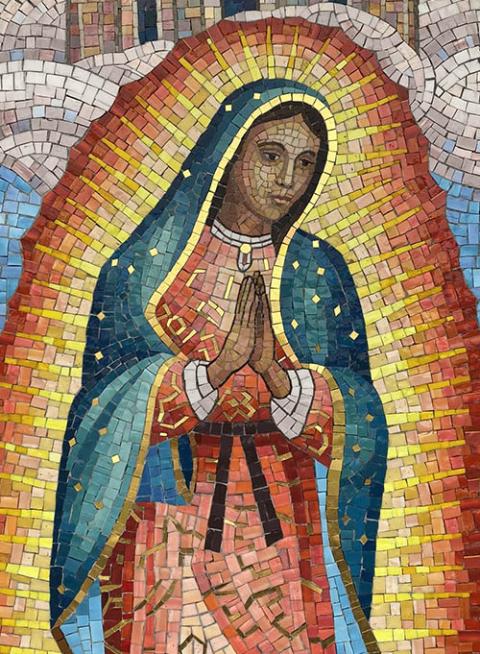

Our Lady of Guadalupe mosaic, St. Juan Diego Catholic Church, Pasadena, Texas (CNS/Texas Catholic Herald/James Ramos)

Does Mary, the mother of God, have those same blue eyes, that same white skin, that same European demeanor despite her Middle Eastern origins? Or do we see Mary, that same mother of God, as Our Lady of Kibeho, Our Lady of Guadalupe, Our Lady of Montserrat?

That same mother of God with skin the color of God's people, clothing that reflects God's human family, eyes full of that same love.

Different versions, yes. But the same story. Creative tension. Paradox.

It might be borderline heretical to say that after completing that course on fairy tales, I felt as though I'd become better equipped to sort through Scripture. All these different — at times, contradictory — stories. And they're all supposed to tell us about God, about God's people, about God's dream for the world.

As we experience more and more of God's story — told more and more by God's people in all their differences and uniqueness and potential — we glimpse more and more of who God is. Always beyond our understanding, greater than our imagination, and yet beckoning us closer and closer.

We want religion — we want God — to be like that "Star Wars" canon: just read it all and know it all. It's all there; it's all linear; it all makes sense. There is an official version, an official understanding — and then there are plenty of wrong views.

God's story is more like these fairy tales, pieces of a great narrative tapestry that stretch back further than we can know, passed down, torn, mended, stitched together into something new, and imitated, duplicated, whispered about because of their beauty. We're still weaving it together. We're still imagining what it might become.

What it might lead to. What it might mean. Where we might show up in the story — and what role we might be asked to play as a result.

That last day of Little Mermaid Dance Camp saw my wife, my 1-year-old and myself huddled together on a hardwood floor with other parents and siblings, eager to witness this much-hyped recital.

The music began — "Look at this stuff; isn't it neat?" — and out danced one of the campers. She did a few moves, then another camper appeared, assuming the role of Sebastian the crab: "Ariel! Don't you like living under the sea?"

Advertisement

That was the cue — all the campers danced out from behind the curtain that had not quite been hiding their eager presence, my daughter included. "Under the Sea" resounded in that small, joyful space. The campers spun and waved and kicked and bowed, smiles all around.

My daughter was clearly quite pleased. Focused though she was on following the routine, she couldn't help slipping us little waves, little smiles. She really did love this story.

Here, then, was another version of that same story. And this version was big enough to include her. She could see herself, be herself, thrive.

We spend a lot of time reading and watching and talking and thinking about fairy tale princesses in our household. Too many princess stories are retellings of the same trope: a woman in need of rescue and romance.

But there are other versions out there, other ways of being a princess. Versions that involve mermaids and towers and long locks of hair.

This version saw the princess dance and smile and at the end of it all run — proud and confident — to embrace her family, eager to see what else the day might bring.