The documentary "Civil: Ben Crump" chronicles Crump's life from agreeing to represent George Floyd's family in May 2020 to the April 2021 verdict that found former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin guilty of second-degree murder. (Courtesy of Netflix © 2022)

Turn on your television, and there's Ben Crump at the forefront of a national racial injustice case. "Civil: Ben Crump" reveals aspects of the famed Black attorney's life and work, which the public usually doesn't see. The documentary chronicles the momentous period in the 52-year-old's life: from agreeing to represent George Floyd's family in May 2020 to the April 2021 verdict that found former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin guilty of second-degree murder.

Premiering in June at the Tribeca Film Festival, the imperfect and tendentious film is streaming on Netflix.

As she did in her Emmy-nominated 2020 film "Becoming," which takes viewers inside former first lady Michelle Obama's tour promoting her eponymous memoir, Black director Nadia Hallgren employs a cinéma vérité style, accompanying the man called "Black America's Attorney General" on his peripatetic quest "for equality and justice for all," as Crump says.

Jazz drummer Makaya McCraven's melancholy soundtrack lends "Civil" a pensive, spiritual quality, although shots of the protagonist sitting in a car backseat, staring out the window feel self-conscious on the director's part.

"Civil" opens as the litigator take a call from Tera Brown, who says her cousin has been murdered by Minneapolis police officers. "His name is George Perry Floyd," she tells Crump, who assures her: "You're not alone, Tera."

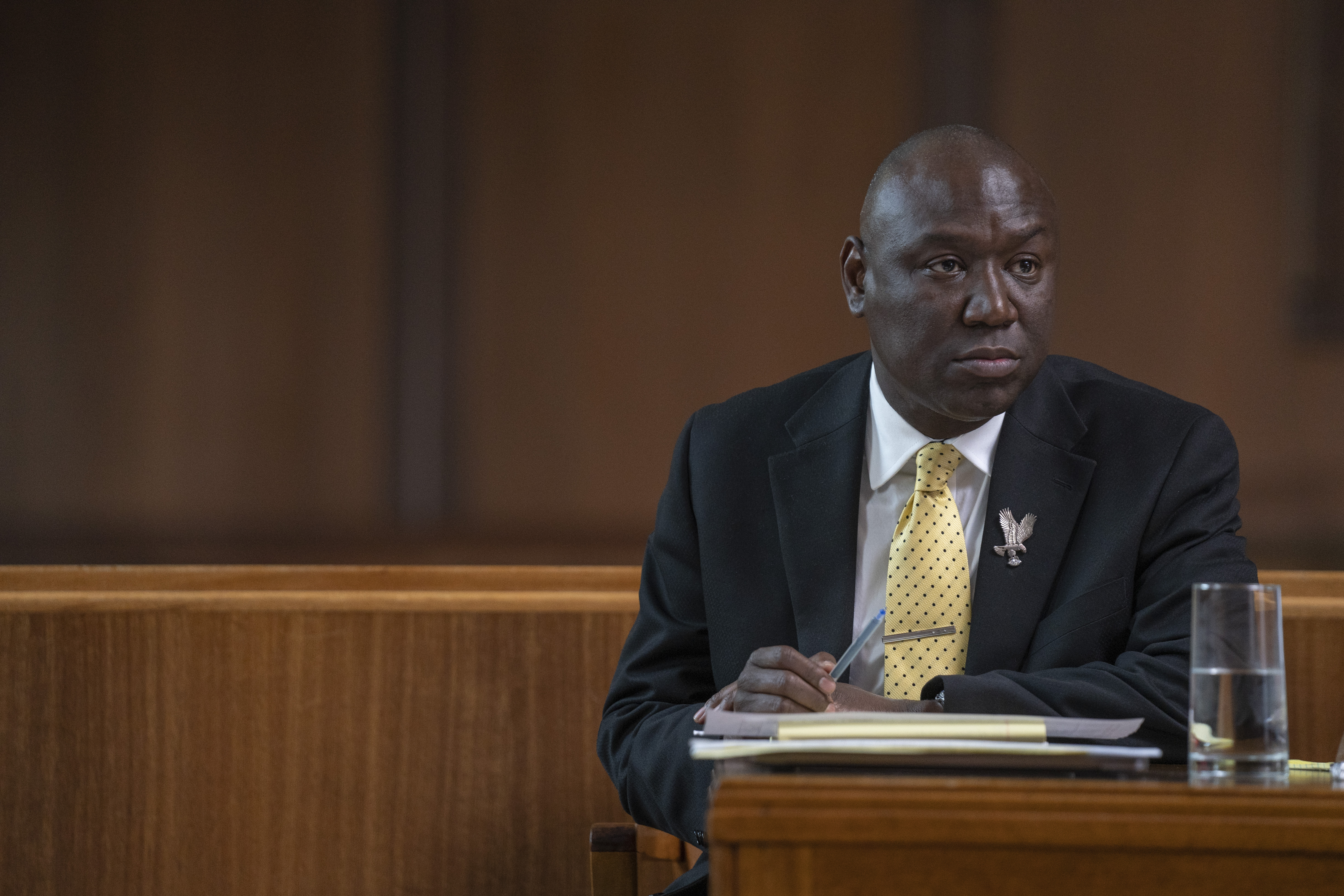

Civil rights attorney Ben Crump, pictured in a scene from the documentary "Civil: Ben Crump," has represented families of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Tamir Rice. He's also worked on lower profile cases, like a group of Black farmers seeking a judgment against Monsanto, whose Roundup weed killer has been linked to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. (Courtesy of Netflix © 2022)

Hallgren understands how engaged her audience has been in the Floyd case and wisely bookends the documentary with that case's pivotal moments. This narrative strategy allows the director to highlight the other important work the attorney did in the 11 months between Floyd's murder and Chauvin's conviction.

The documentarians highlight 11 other individuals or groups Crump's firm has defended. A number of these cases involved police malfeasance and some — such as 26-year-old Breonna Taylor, the medical worker from Louisville, Kentucky — will be well known to viewers. The filmmakers emphasize that the cases they detail represent only a fraction Crump's team handled during this timeframe.

Crump also stresses that the high-profile criminal justice cases for which he has become well known reflect the minority of cases his firm takes. His work on behalf of Black farmers is a good example.

National Black Farmers Association founder John Boyd's eloquent description of their plight will engender empathy from viewers. These farmers, the fourth-generation Virginian notes, once owned 15 million acres of land, but now own only 3 million. At the turn of the 20th century, he says, there were 1 million Black farmers. Now there are 45,000.

Crump is working with the farmers to secure a judgment against Monsanto, whose Roundup weed killer has been linked to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Hallgren addresses the principal criticism directed at the attorney: that he's an opportunist. (The Revs. Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton have heard the same criticism, but you wonder why white leaders don't face the same level of scrutiny.)

Crump won a record $27 million civil judgment for the Floyd family. This kind of lucrative award has prompted charges he's in it for the money. Viewers may be able to dismiss the Fox News pundits who level the accusation in the film, but when distinguished journalist Ted Koppel asks the litigator in a TV interview: "What about the money?" the assessment becomes more credible.

In a May 2021 BBC News profile of Crump, Samaira Rice offers this forthright critique. The mother of 12-year-old Tamir Rice, a Black boy killed by Cleveland police in 2014 because they mistook his toy gun for the real thing, says of Black Lives Matters activists: "(They) need to step down, stand back, and stop monopolizing and capitalizing (off) our fight for human rights. In the case of Tamir Rice, it was even questionable as to whether Benjamin Crump knew the laws in the state of Ohio. I fired him 6-8 months into Tamir's case."

In the film, the attorney asserts he's an: "unapologetic defender of Black life, Black humanity and Black liberty," adding that his "partners would rather I'd not be doing civil rights cases. They think I've done enough. We could make more money more easily and more of it."

Advertisement

One of the documentary's postscripts confirms what the filmmakers think of these reproaches. It celebrates the $184 million judgment Crump's team won on behalf of Blacks discriminated against by banks.

Beginning with its awkward, puzzling title, "Civil" is significantly flawed. The title refers to the kind of law Crump practices, but it disserves the film's subject. "Ben Crump: America's Black Attorney General" seems more apt.

"Civil" also doesn't go as deep as you want it to go.

Crump briefly speaks of his admiration for late Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall. He was his "personal hero," because Marshall "taught me to go into courtrooms and always argue what is right." But we want to know more about the fabled civil rights leader's influence upon the attorney.

Viewers will also want to know why the Omega Psi Phi fraternity was, for the Crump, "the foundation for who I was to become." Omega Psi Phi is arguably the country's preeminent Black fraternity — Michael Jordan, Count Basie and Langston Hughes are among its many illustrious alumni — and making that connection would have enhanced the audience's experience.

The documentary's final shot sums up the kind of the film the documentarians wanted to make. In it, the protagonist is viewed ascending in a translucent glass elevator, almost as if divinely appointed. Veering toward hagiography, "Civil" will likely limit its viewership to those who concur with the filmmakers' assessment.