(Unsplash/Sharon McCutcheon)

Queer theory reclaims and celebrates the erotic — the sexual, the intimate and the sensual. But are there ways in which queer theory itself is erotophobic?

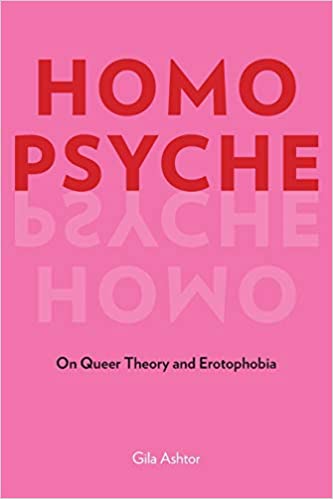

This question guides Gila Ashtor's bold new book, Homo Psyche: On Queer Theory and Erotophobia. Ashtor, a psychoanalyst and critical theorist, takes on gender theorists such as Eve Sedgwick and Judith Butler and uses a metapsychological approach to show that the field of queer theory "remains far from grasping that sexuality's radical potential lies in its being understood as 'exogenous, intersubjective, and intrusive.' " Ashtor helps us to see how the erotic enlarges sexuality and infuses our everyday lives. For Catholics, Ashtor can help us to consider liberation theology more intimately and relationally — ultimately, more queer.

I admit that I find myself wondering what Ashtor would think of a book review for Homo Psyche appearing in National Catholic Reporter. I imagine that is worth at least a chuckle, given the irony of the Catholic Church being perhaps the poster child of a sort of blatant erotophobia that many queer (and straight) Christians and Catholics consciously combat and resist — not much metanarrative here.

Further, as provocative as it is to bring queer studies and Catholic studies together, there are certain unreconcilable dissonances: something that politically queer Catholics feel in our bodies as much as we see it manifested theoretically. But I hope to show, both here and in my work as a queer Catholic theologian, that our Catholic identity can benefit from the questions that queers ask and the approaches we take to the world around us.

(Unsplash/Raphael Renter)

Homo Psyche begins with a broad understanding of queer studies. Queer theory is part of the movement toward poststructuralist thought that considers the role of power in knowledge production and that emerged at the intersection of women's studies and gender theory. As far as fields go, that of queer theory and hermeneutic is relatively new: historian Teresa de Lauretis is credited with coining the term at a 1991 conference. Queer theory is the study of gender and sexuality from a distinct political standpoint. It mostly utilizes lesbian and gay studies, critical race theory and feminism via a variety of disciplines to create structural critiques of political, social and economic systems that contribute to oppression.

The field surrounding queer theory is also notoriously self-critical: In 1994, de Lauretis herself was already rejecting the term, criticizing its use as a marketing strategy, as Ashtor notes in her introduction.

Writer Annamarie Jagose says that queer declares itself "a category in the process of formation." To use Ashtor's words, it "proudly [insists] on the instability of its own aims and projects." Jagose defines queer as "those gestures or analytical models which dramatize incoherencies in the allegedly stable relations between chromosomal sex, gender and sexual desire." Queer positions itself against, according to theorist David Halperin, "the normative, the legitimate, the dominant." German philosopher Max Horkheimer insists that a queer hermeneutic is "suspicious of the very categories of better, useful, appropriate, productive and valuable."

In these ways, queer theorists are allergic to binaries and norms, comfortable with and even attracted to the unknown, uninterested in programs of reform and seduced by the disruptive and provocative. Ask a queer theorist whether the glass is half empty or half full and the response is, "The glass is broken."

Ultimately, queer theory is defined by its lack of definition and is well known for difficult, heady readings. For some, these trends can be quite frustrating. However, queer theory is ultimately rooted in queer experience struggling against social structures, and these writings can truly be imaginative and spiritual.

Our Catholic identity can benefit from the questions that queers ask and the approaches we take to the world around us.

If queer theorists are prone to disruption, provocation and self-criticism, Ashtor is certainly all of these things. Homo Psyche's main concern is the way that the field of queer studies has been split into those who affirm a psychoanalytic method and those who reject psychoanalysis outright. That the field has a distinct aversion to the use of traditional psychology is unsurprising, given that queerness originated within it as a sort of disorder. But Ashtor shows how metapsychology has the potential to expand our understanding of sexuality in a way that can be useful to the field, whose psyche has tended toward the erotophobic in the way that sexuality has been narrowly conceptualized even by those with the most erotophilic intentions.

Ashtor defines erotophobia as "the denial of 'enlarged' sexuality that leads to and enforces the belief in psychic self-begetting." That is a lot to unpack; the field of queer theory is nothing if not dense. Metapsychology is concerned with our unconscious metanarratives. Therefore, Ashtor aims to consider the ways that some of the most influential theorists with complex, compelling and provocative theories still might be considered to write within a paradigm that considers sexuality to be an individual phenomenon rather than something driven externally and by a variety of subjects around us — Ashtor's enlarged sexuality. Certainly, every author Ashtor treats would agree that queer sexuality is erotophilic in the sense that Ashtor means it, but do their intentions hold up in their writings? Ashtor aims to find out.

Ashtor performs six "tests" of her method on various seminal theoretical concepts within the field of queer studies with compelling outcomes. She attempts to treat each author authentically by respecting the breadth of their work, noting "while each chapter strives to uncover the erotophobic effects of even the most erotophilic intentions, my interest is primarily in tackling, and dismantling accordingly, those concepts which are popular and prevalent in the field so as to create opportunities for theoretical innovation." Hers is a deconstructive text with the aim of illuminating areas for future reconstruction.

Homo Psyche may best be seen as a resource for understanding some of the critiques that second-generation queer theorists are waging, out of faithful infidelity, against the first-generation heavy hitters (remember how young the field is). Each chapter can stand alone as a critical treatment of a major theoretical concept that has defined the field thus far, and they come together as a multifaceted, field-wide critique.

If you are new to queer theory, the chapters may require some pearl-clutching along the way; even as a graduate student of queer theology and ethics, the closest thing I have to pearls was certainly clutched during the boundaries conversation of Chapter 3 as Ashtor treats sexual abuse and boundaries violations within queer theory. Perhaps a bias due to my love for the writing of Sedgwick, I was especially enamored with Ashtor's Chapter 1 discussion of the ways in which losing an erotophobic psyche would allow our queer hermeneutics to become more effective through an expansion of our understanding of the subject.

Advertisement

Ultimately, I was left wanting a conclusion from Ashtor and more concrete discussion of what types of innovations and new interpretations we might expect if we can "wake up" to the metanarrative of erotophobia running through the field of queer studies.

What can Catholics take away from this provocative study of the erotic? I think Homo Psyche is relevant specifically to our community for a few reasons. Firstly, it allows us to question the role of the erotic in the project of liberatory frameworks of theology and ethics. To be distinctly queer, theologians interested in liberation should question the metanarratives running through our own fields and whether they can be enlarged to be queer inclusive and, dare I say, erotic. I think this would look like taking a more complicated and interdisciplinary approach to gender and sexuality and complexifying concepts such as attraction and desire. I have taken a stab at what an erotic interpretation of Eucharistic theology might look like.

Secondly, Homo Psyche is a critical field intervention that takes major players as subjects worthy of critique. I think that theologians and ethicists would do well to learn from the field of queer studies that embraces self-criticism and that is not only open to but also actively in pursuit of new aims, ambitions and projects.

Sedgwick privileged "obstinate intuition"; as a young writer, she was consistently enamored with the "loose ends and crossed ends of identity" rather than places where everything could be neatly aligned. Queer ethicists and theologians certainly exist at this intersection of provocation, and Homo Psyche is a wonderful intervening resource that encourages the further exploration of Sedgwick's loose and crossed ends from which liberation theology can benefit.