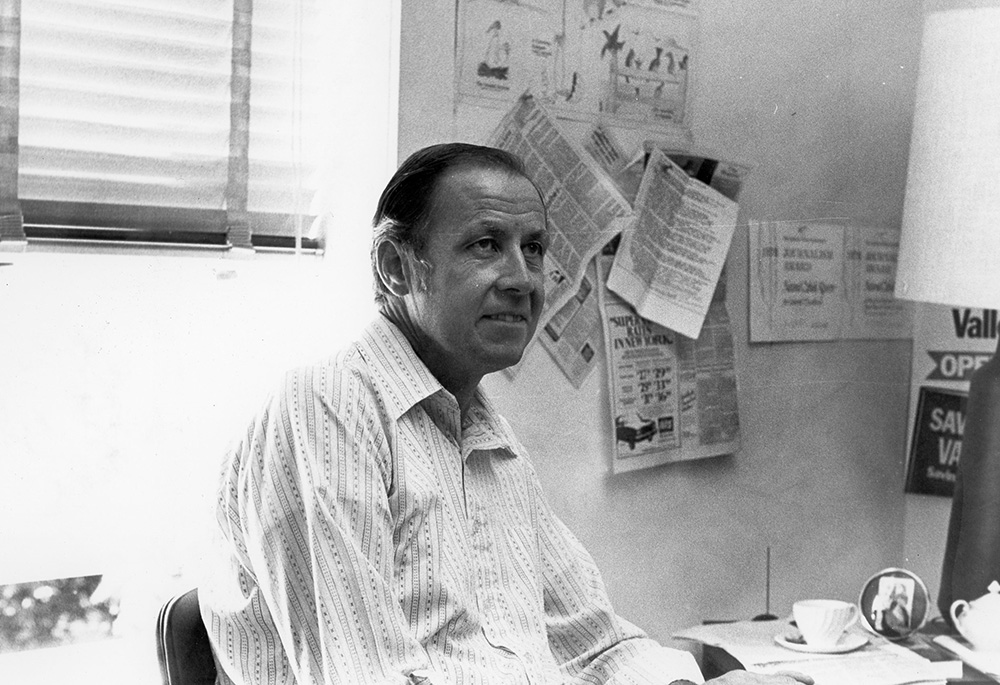

Fr. Michael Gillgannon in October 1979 (NCR photo/Dawn Gibeau)

Fr. Michael Gillgannon, missionary priest from the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph, Missouri, and a leading expert on Latin America, died June 19. He was 88.

For more than 30 years, Gillgannon wrote for NCR from Bolivia in columns critical of U.S. foreign policy and in support of church reform efforts in the region. He uniquely combined his pastoral experience, an understanding of history, and international affairs.

"He lived for his ministry," said Fr. Pat Rush, a priest and former vicar general from the Kansas City-St. Joseph Diocese. "He was totally absorbed by the social gospel as he saw it." Rush described Gillgannon as "a very gentle man."

"Can't imagine him dealing with dictators in Latin America. He always wanted to be at peace with people," Rush told NCR.

Fr. Chuck Tobin, another priest from the Kansas City-St. Joseph Diocese, described Gillgannon as having "a prophetic vision of the Gospel values that were often being ignored either by the various church communities or nation-states."

"Mike, indeed, lived Luke 4," said Tobin. "He brought good news to the poor and sight to the blind and by that, I mean opening the eyes of the nation to injustices and to the needs of the oppressed."

Dominican Sr. Barbara Reid, president of the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, told the story of encountering Gillgannon in the early 2000s, when the priest came to hear her give a talk on a feminist interpretation of the Scriptures. She remembers him asking her if she knew anyone who could do a similar presentation in Spanish. Reid had taught Spanish for six years. So, she agreed and ended up traveling to La Paz to speak on several occasions.

"I learned so much from him," Reid told NCR, adding: "He helped shape my research."

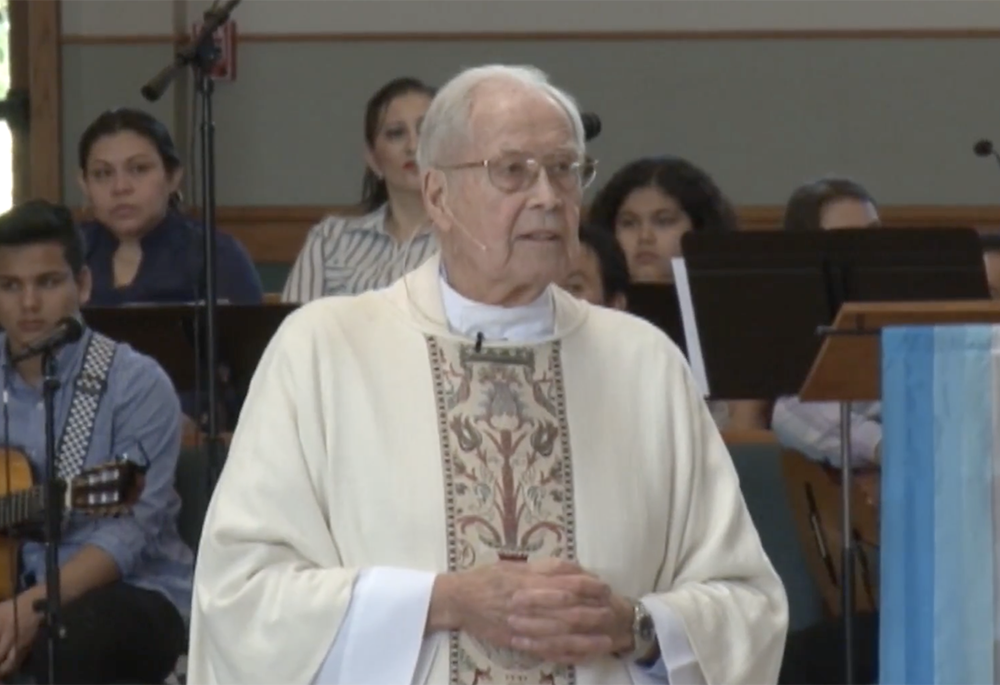

Fr. Michael Gillgannon preaches in Spanish and English during a Mass celebrating his 60 years as a priest on May 6, 2018, at St. Sabina Catholic Church in Belton, Missouri. (NCR screenshot/YouTube/Fr Michael Gillgannon)

Gillgannon was born in Kansas City, the youngest of nine children, four of whom became priests or members of religious orders. He was ordained in 1958. Like many other priests of his generation, he was highly influenced by the Second Vatican Council, which unfolded in the mid-1960s and set off major change throughout the world and especially in the churches of Latin America, as many opted for what they called the "preferential option for the poor."

U.S. church renewal was also in the air in the late 1960s. In 1966, Gillgannon served on the advisory committee of the U.S. bishops' conference for the post-Vatican II reorganization of Catholic campus ministry in the country. He became the Catholic campus ministry national secretary, helping to rethink and rewrite campus ministry programs.

In 1974, he moved to La Paz, Bolivia, to become a missionary. He served as a pastor, an episcopal vicar and as the national chaplain for Bolivian campus ministry. He once wrote that he thought he would simply complete a five-year stint doing missionary work, but little did he realize how "fascinated and involved" he would become "with struggles that were changing everyday life and the Catholic Church." He stayed nearly 40 years, returning to Kansas City in 2012 to minister to the Spanish-speaking community and to continue his lectures on Catholic social ethics and economic development.

For his work in Bolivia, Gillgannon was awarded two honorary doctorates. In 2000, he was given the title of Doctor of Sacred Theology by the South Florida Center For Theological Studies in Miami. In 2004 he was given the title of Doctor of Ministry by College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Advertisement

Gillgannon was a scholar. He devoured and analyzed books. He published when he could. On trips back to the U.S. between 1974 to 2012 he would consult with members of the U.S. bishops' Latin America desk.

His goal, he explained, was to provide ethical and religious insights from his experiences. Though years and circumstances changed, his message remained largely consistent: U.S. economic and social policies are exploiting the poor of Latin America.

He did not shy away from criticisms of the U.S. Catholic hierarchy, who, he believed, seldom preached the social teachings of the Catholic church. He summed up his advice for U.S. church leaders in a blog he posted in 2018 on his website:

Bishops and priests, Get out of your ghetto. Learn why you live well in a rich and comfortable nation, which you take for granted as do your faithful. Study, preach and teach Gaudium et Spes, Pacem in Terris, Populorum Progressio, [and the documents of] Medellin and Puebla. And please do not say that the economics and politics of U.S. international relations is too complicated for ethical discussion or popular preaching. Your ignorance will only confirm those who say your moral authority is undermined by your selectivity.

Live the poverty, personal and ecclesiastical, which you must now preach to a profligate nation. There is no vocation problem in the United States. There is simply no reason to choose the priesthood or the religious life where comfort and conformity are the norm. Where's the challenge? Where's the idealism? Where's the sacrifice?

In 2018, Gillgannon published a reflection on his life as a missionary, called Padre Miguel. He said he wrote the book to inspire interest in Latin America and stimulate people to ask critical ethical questions and reflect on social justice.

During his life and ministry, Gillgannon held to the hope that information was vital and that Catholic social teachings had the necessary ingredients to form good consciences. He felt compelled to provide the necessary information, grounded in his missionary experiences, in the belief U.S. Catholics could influence and change the direction of U.S. foreign policy. It was a big ask.

Just weeks before his death, I visited him in a Kansas City hospital room. His health was declining. He was both lighthearted and serious, in many ways, the same Gillgannon. He spoke and I mostly listened. He denounced U.S. foreign policy as it continues to affect the poor of Latin America. Those poor have never been abstractions to Gillgannon. I thought to myself he would carry the burden of his concerns to his last breaths, his mission never fully completed, such is the weight of his missionary encounters and the desire to stay faithful to the Gospels.

No doubt, his many friends are praying that those concerns and that anguish have been rewarded, and he lives in eternal peace.