Barbed wire near the Birkenau section of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration-death camp in Poland (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

My Good Friday experience came early this year. I can pinpoint it to the day in early March when, during the start of an assignment covering the Ukrainian refugee crisis in Poland, I visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau prison and death camp.

I was still mourning the start of the war in Ukraine, grieving over what I thought, and still believe, is a tragic, unnecessary and immoral act of state-sanctioned violence, when I steeled myself for a half-day visit to what is perhaps the most visible symbol, even fulcrum, of systematic evil and terror anywhere on Earth.

An "accursed kingdom" is how Auschwitz survivor and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel described it.

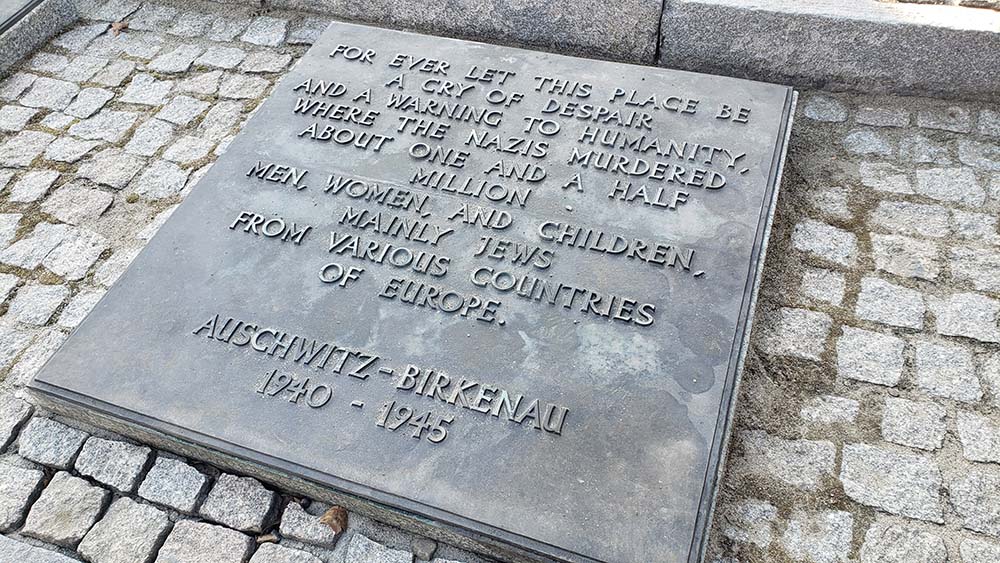

Accursed indeed. Not far from where the crematoria once stood, a stark memorial declares what is being remembered: "FOR EVER LET THIS PLACE BE A CRY OF DESPAIR AND A WARNING TO HUMANITY, WHERE THE NAZIS MURDERED ABOUT ONE AND A HALF MILLION MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN, MAINLY JEWS FROM VARIOUS COUNTRIES OF EUROPE. AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU 1940-1945."

A marker near the destroyed crematoria within the Birkenau section of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration-death camp commemorates the more than 1 million people who were killed at the facility. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

The enormity of that fact — underlined by the massive capitalized letters set in granite stone — weighs heavily on visitors, and the mind seeks answers. During my visit I put aside questions about theodicy — where was God? — and focused more on the question of where was man? Where were humans? Where were humans in the face of the creation and implementation of a sophisticated and well-executed system of mass murder?

"Human beings did this," I thought as I walked along the still-intact railroad tracks on which souls from Hungary, Poland and other European countries were delivered to their untimely deaths. "Human beings did this."

And they did it with precision, thought and calculation, as the great Soviet war correspondent and novelist Vasily Grossman said about another notorious death camp in Poland. "Hitler's regime," Grossman wrote after the 1944 liberation of Treblinka, "harnessed these qualities for a crime against humanity."

These qualities were tangible and visible, and visitors to Auschwitz see that in very concrete ways. It's the details that I remember most from my visit: the eyeglasses snatched from the camp arrivals and now displayed in giant mounds; the cramped bunks where prisoners slept, six to eight in a row; a camp commander's desk on which documents and papers were signed, sending countless people to their deaths — an implement of what Hannah Arendt called a Schreibtischtäter, a "desk murderer."

One of the displays at the Auschwitz concentration camp shows the desk of a commander who would execute the sentences imposed by the Gestapo court. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

And I was struck by the ways in which humans continue their ways, even amid the memory of so much horror: There are now homes surrounding the camp where people presumably live comfortable lives. I saw a man taking a leisurely afternoon stroll with his dog on the camp perimeter. I also saw young visitors to Auschwitz taking selfies near the barracks were people starved or awaited their deaths.

Humans are a strange species, I thought. We are hardwired to remember and yet we so often indulge in avoidance, repression or denial.

And we keep making the same tragic mistakes. A few years back, Bruce Ratner, the chairman of the Museum of Jewish Heritage — a Living Memorial to the Holocaust and someone who lost family at Auschwitz, spoke to a Time magazine reporter about the Holocaust at a time when, pre-pandemic, the New York City museum hosted a major exhibit about Auschwitz.

"We all hoped that after 1945, we would not hear about mass murders and immigration and refugee issues again, and yet they're top headlines today," Ratner said.

Look where we are now in 2022.

A demonstration against the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February in Hamburg, Germany (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

I want to be careful here. I don't want to overstate the similarities between the Holocaust and Russia's invasion of Ukraine — there are quite obvious differences, including the fact that Russia has not embarked on a campaign of racial extermination against Ukrainians. (However, there are growing concerns that, in targeting civilians, Russia is committing genocide and may be seeking the elimination of the Ukrainian nation.) In short, here we are, once again, facing more dehumanization, more killings and more death on the continent of Europe.

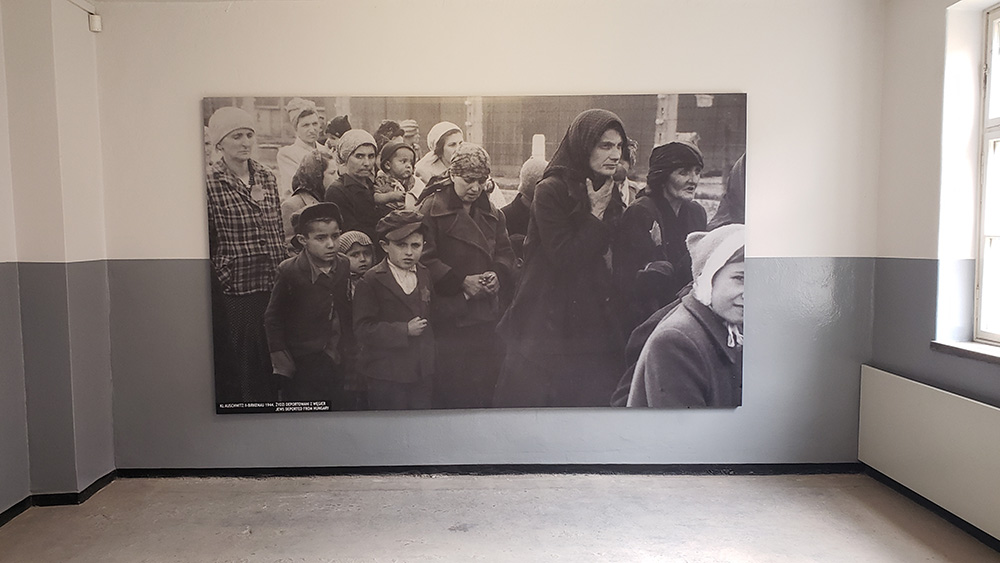

One exhibit at Auschwitz included a massively enlarged photograph showing Jewish deportees from Hungary arriving at Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944. They were destined to die. Fortunately, the same can't be said for most of the refugees fleeing Ukraine. That's a crucial difference. Yet the image resonates today as we witness the streams of refugees crossing borders and read news about war crimes against civilians, like in Bucha, Ukraine.

An enlarged photograph at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration-death camp shows Jewish deportees from Hungary arriving at the facility in 1944. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Unfortunately, ours is still a world of the traumatized and the displaced.

And it is still a world grounded in the misguided and pernicious idea that certain people or nations are exceptional. Grossman wrote that what prompted the construction of an Auschwitz or Treblinka "is the imperialist idea of exceptionalism — of racial, national, and every other kind of exceptionalism."

Though Russian President Vladimir Putin is trying to spin the absurd notion of Russia under threat from Ukraine, which he claims is a Nazi state (despite having a Jewish president), the cornerstone of his war is the idea of an expansive, imperial and exceptional Russia, a Russia of power and might.

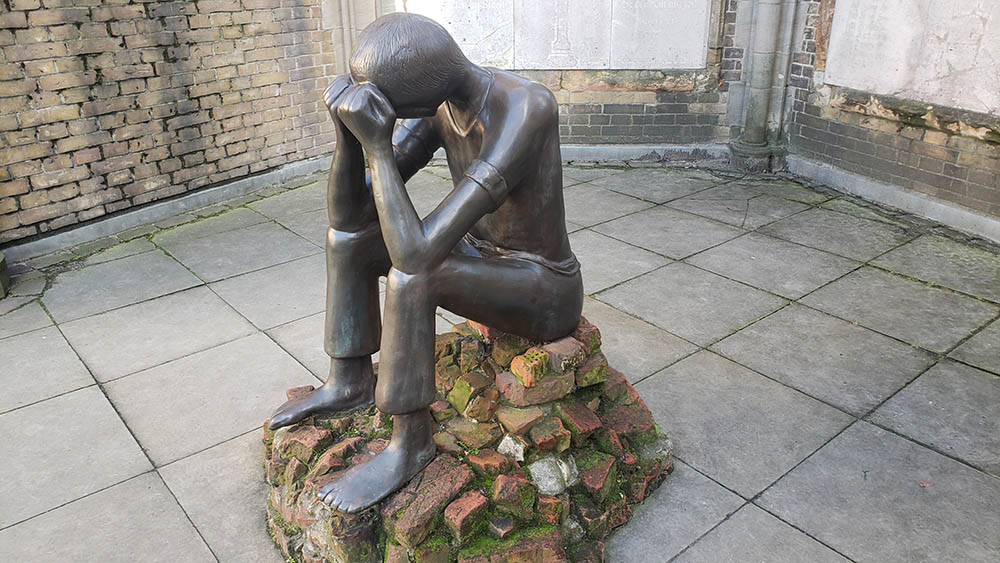

A sculpture at the remains of St. Nikolai Cathedral, which was largely destroyed during the 1943 Allied firebombing of Hamburg, Germany, mourns the horrors of war. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Unfortunately, exceptionalism is not only about nations. Digging into a 2002 volume of essays and reflections on the Holocaust by both Jewish and Christian scholars and theologians, I was sobered to read Catholic theologian Rosemary Radford Ruether's necessary reminder of the very real responsibility Christianity has for antisemitism.

"The Christian theological teaching that the Jew is reprobate in history until the end of time translated itself into a practice of social denigration," she wrote.

Picking up on that theme, Catholic literary scholar Harry James Cargas asked if it is possible to be a Christian today given that death camps like Auschwitz were for the most part "conceived, built, and operated by people who called themselves Christian."

The train tracks within the Birkenau section of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration-death camp. Trains from throughout Europe arrived with prisoners, most of them Jews, with most sent immediately to gas chambers. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

I had thought of that very question of Christian responsibility as I walked along the railroad tracks of Auschwitz-Birkenau. A month later, and on the day we mark Good Friday, that question still startles and unsettles me.

Perhaps this is the day to take such questions seriously and think of repentance — what Ruether calls real repentance: "A repentant Christianity is a Christianity," she wrote, "which has turned from the theology of Messianic triumphalism to a theology of hope." Put another way: We need to embrace a Christology that recognizes the humanity of Jesus, a young, radical Jewish man consigned to an early, agonizing and painful death — bound, brutalized and broken, mocked, scorned and reviled.

Advertisement

Ruether's idea of hope is born of a Christology grounded in humility. It relies on an understanding that, in the face of the horrors of our time — horrors that "fill our souls with reproach and everlasting shame," as Jewish theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote in 1976 — we must be aware of another power. That power affords us a glimpse into a better world, a world without imperial designs.

On an earlier part of my recent trip to Europe, I visited a history museum in Hamburg, Germany, that did not flinch in discussing the Nazi era, or, for that matter, the Allied firebombing of Hamburg in July 1943. That act destroyed much of the city and killed about 37,000 German civilians. (A memorial commemorating the event has been established at another site, the remains of a cathedral largely destroyed during the bombing.)

A photograph at the Hamburg Museum shows crowds celebrating the launch of a ship in Hamburg, Germany, during the Nazi era. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

One photograph at the Hamburg Museum that has stayed with me these last weeks is that of a christening of a large ship in Hamburg's harbor sometime in the 1930s, flags aflutter, crowds giving the Nazi salute and giddy with triumphalism.

What a sham, I thought. The strength of any society is not due to its armaments, its projection of power or its celebratory vain and vacant pomp, but how it treats its most vulnerable — its poor, its elderly, its children.

"Only in His presence," Heschel wrote, "shall we learn the glory of man is not in his will to power, but in [the] power of compassion."

Compassion. In the face of my visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau and against a backdrop of another war in Europe, compassion is my watchword this Good Friday.

The site of the St. Nikolai Cathedral, which was largely destroyed during the 1943 Allied firebombing of Hamburg, Germany, is now a memorial commemorating the war. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)