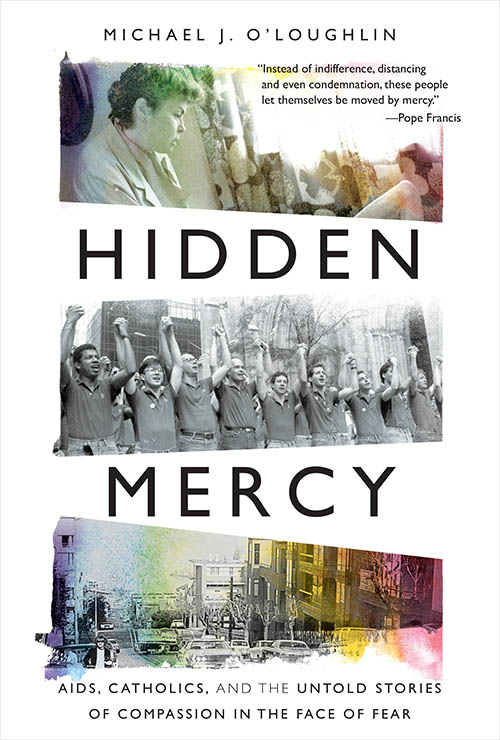

Demonstrators hold signs in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City on Aug. 2, 1987, to protest the appointment of Cardinal John O'Connor to a national AIDS panel, which gay rights activists said was "stacked" against them. (AP/Mario Cabrera)

In Hidden Mercy: AIDS, Catholics, and the Untold Stories of Compassion in the Face of Fear, author and reporter Michael O'Loughlin draws us into the mystery of the faith by resurrecting, through storytelling, the lives of those lost during the AIDS/HIV crisis and flooding a light of hope into the chasm of despair.

Hidden Mercy, published by Broadleaf Books in time for World AIDS Day, reframes history as not rote and binary — with the LGBTQ community suffering on the one hand and the Catholic Church welcoming the plague on the other. Instead, it provides a dynamic look at how Catholic faithful, including LGBTQ Catholics, struggled, as they do today, to carry out the Catholic mission to love mercy, do justice and walk humbly with God, while overshadowed by a hierarchy with a much different agenda.

O'Loughlin, who has been reporting on the intersection of the Catholic Church and the LGBTQ community for more than a decade, including in the podcast "Plague: Untold Stories of AIDS and the Catholic Church," recounts some of those same stories in the book. They include Carol Baltosiewich, then a Hospital Sister of St. Francis, who started an AIDS ministry in Belleville, Illinois, and the "gays and grays" at Most Holy Redeemer Parish in the Castro in San Francisco.

While the church refused to shift its theology of human sexuality or provide special dispensation for the use of contraceptives as a means for mitigating the spread of the virus, religious sisters, priests and laypeople alike moved into action, O'Loughlin recounts, to show compassion to those suffering.

In the book, we meet priests with AIDS, learn about a Catholic Worker house for homeless people with HIV/AIDS in Oakland, California, and, along the way, learn a bit about O'Loughlin's struggles with Catholicism.

Hidden Mercy is healing not in that it attempts to say "not all Catholics!" but instead by the way it shows that Catholicism, in its truest self as the manifest love of God, still lives, in spite of itself. And it is in this healing that O'Loughlin conjures hope.

O'Loughlin has tracked the ebbs and flows of what has felt like meager progress in the church's recognition of the full humanity of LGBTQ people, holding in tension the significance of moments like Pope Francis' support of civil unions for same-sex couples, without denying the harrowing reality of church leadership actively, and aggressively, attacking LGBTQ people.

But the stories O'Loughlin centers — stories of pain and suffering, ministry in the face of true horror and impossible odds, death without dignity, and an institution hellbent on crucifying Christ's precious little ones — always leave me suffocating with grief and lamentation.

Advertisement

It was early April 2020, a little before Easter, when I first listened to O'Loughlin's podcast. At the time, I was leading religious engagement and mobilization for a large LGBTQ civil rights organization, and as Lent waned, and a different but deadly new pandemic raged, I was struck by an onslaught of emotions.

Growing up gay and Catholic and serving as a public theologian and organizer primarily in the sphere of LGBTQ justice, I've grown more than accustomed to the weathered narratives around religion and the LGBTQ community, narratives that typically create a false dichotomy wherein you can't be a person of faith and LGBTQ, contrived narratives that falsely claim that you can either protect religious freedom or LGBTQ rights, but not both.

It's easy to get lost in the fury of the history, the grief of what has often been referred to as a lost generation, and the indignation at the fact that HIV/AIDS continues to destroy communities around the world. The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 680,000 people died from AIDS-related causes in 2020 alone, a grim reality as we mark another World AIDS Day.

Today, we continue to face a Catholic hierarchy that is overwhelmingly opposed to civil rights and protections for the LGBTQ community. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has continued to take a militant position against the Equality Act, a piece of legislation that would, among many things, ensure that LGBTQ people are protected from discrimination in health care. The Catechism of the Catholic Church still refers to "homosexuals" as "intrinsically disordered," and the church's only approved means of mitigating the spread of HIV today is, ignorantly, celibacy.

Michael O'Loughlin, author of "Hidden Mercy: AIDS, Catholics, and the Untold Stories of Compassion in the Face of Fear" (www.mikeoloughlin.com)

And yet in response to O'Loughlin's chronicling, Francis sent him a letter, offering his gratitude and blessing both for O'Loughlin's ministry and the ministry of those who saw, and continue to see, Christ in the face of those with HIV/AIDS. This declaration of mercy is characteristic of Francis, who has attempted to reframe how Catholic faithful engage with the LGBTQ community — both within and beyond the walls of the church.

While this response does little to restore the destruction the church has caused, it reflects what O'Loughlin teaches us through Hidden Mercy — that though an institution can harbor terror, it can also be a means of spreading extraordinary compassion. These extraordinary displays of compassion from these hitherto-unacknowledged saints provides us not just a window into the dynamic history and present of the Catholic Church, but it offers a blueprint for what it means to live out, as Francis would have us, Christ's parable of the good Samaritan.

In Fratelli Tutti, Francis writes, "By his actions, the Good Samaritan showed that 'the existence of each and every individual is deeply tied to that of others: life is not simply time that passes; life is a time for interactions.' "

He goes on to say, "The parable eloquently presents the basic decision we need to make in order to rebuild our wounded world. In the face of so much pain and suffering, our only course is to imitate the Good Samaritan."

What O'Loughlin does through Hidden Mercy is show us that all along, there were, in fact, courageous Catholics, often defying their own leadership to live out Christ's call to heal our wounded world. Though heroes of the faith were not able to heal what remains an incurable disease (though an exceptionally treatable one in ways that significantly mitigate spread), their stories have the power to heal a broken world by inspiring us all to a discipleship that reflects a commitment to love in action.

Discipleship, the Gospels teach us, begins with asking questions. Jesus' telling of the parable of the good Samaritan is spurred on by a lawyer asking a series of questions, most importantly, "Who is my neighbor?" Church leaders have often failed to steward this question in their own lives and in the lives of the faithful. The parable teaches us that everyone is our neighbor, and that those in need most especially are our siblings.

The church overwhelmingly has abandoned this ethos in its response to the spread of HIV/AIDS, a pandemic that remains a crisis, albeit one that far too many have moved on from.

O'Loughlin's book is a call to discipleship through both story and action. It doesn't simply invite us to ask new questions, but gives us permission to ask the questions we've kept to ourselves all along — questions about identity, belonging and welcome. It demands that church leadership examine themselves, and not just the church's historic failings but its present plague-spreading policies and doctrines, and how they can, instead of being ministers of death, be prophets of life, and life abundant.

The prophet Jeremiah opens the Book of Lamentations with, "How deserted lies the city, once so full of people!" A haunting verse that summons the anguish of a community devastated by a plague some church leaders dared called the will of God. A generation once vibrant and full of people succumbed to not just the catastrophic impact of the disease, but to the theological malpractice and failure of the Catholic Church's leadership. O'Loughlin's deep dive into this history provides a means of healing, hope and inspiration.